Economy

Government Can Carve Out More Fiscal Space To Boost Spending Without Any Downside Risks

- Restarting growth would require the government to spend — and spend in a manner that does not deteriorate either the balance of payments or induce inflation.

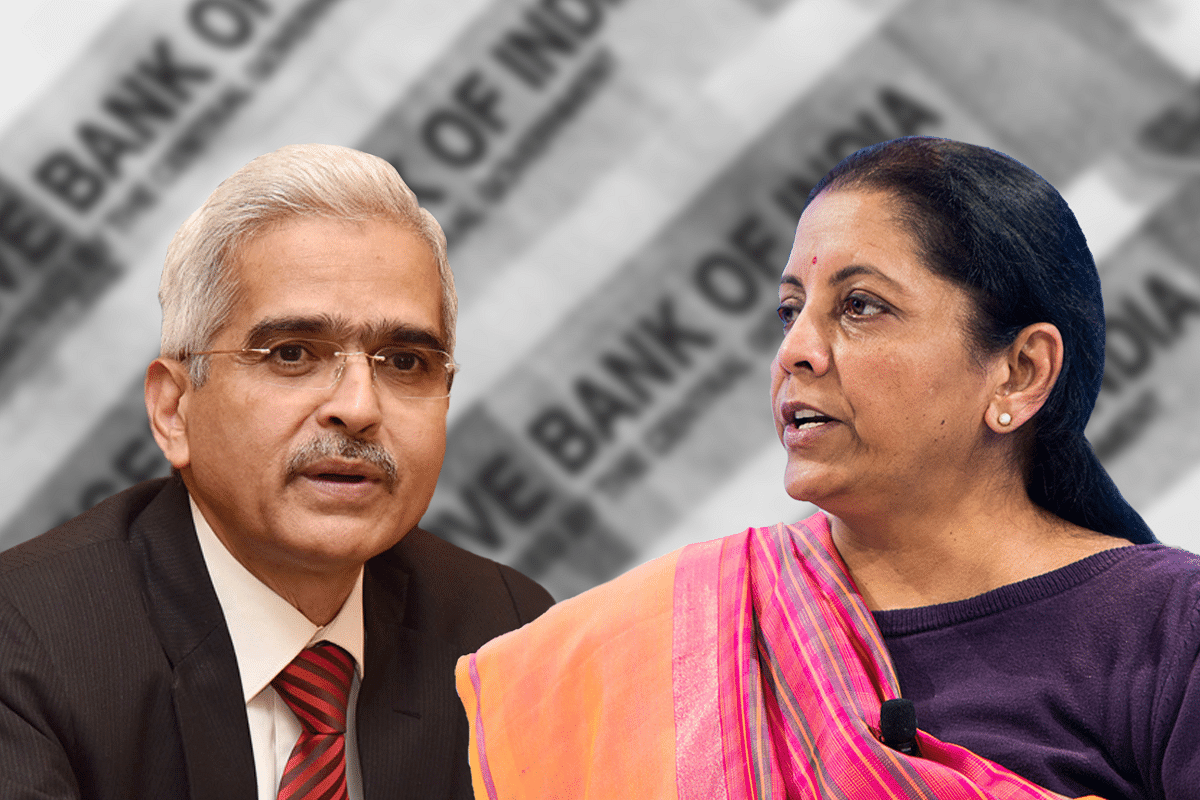

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das.

Since March 2019, successive columns have explored how the world has changed significantly over the last few decades — and that this change needs to be acknowledged more so by our policymakers, economic thinkers, and central bankers.

At the crux of this rethink is the fact that fiscal deficits do not matter as much as we think they do.

This stems partly from what is termed as Modern Monetary Theory (read a joint article with Pragya Gugnani that explains Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) here).

The other reason is that there are only two binding constraints on the fiscal front and they are in the form of Balance of Payments constraint and inflation.

Both of which, are more a function of how the fiscal expenditure is utilised rather than an increase in the expenditure itself.

The present pandemic has forced governments to insulate their economies from the extent of disruption that has been caused due to lockdowns and other such measures.

Consequently, countries have rolled out expansive fiscal programmes to prevent bankruptcies. India too has rolled out a similar programme — along with an ambitious reforms package.

However, to assume that there is limited fiscal space would not be entirely correct.

This is important as I’ve previously argued the limited fiscal space which requires the RBI to do heavy lifting on the recovery — however, proactive monetary policy can ease fiscal space and enable the government to act.

This is the essence of MMT and it explains the expansive packages announced by several advanced economies.

To put things in perspective, advanced economies in total have a debt equal to 128 per cent of the global gross domestic product.

In contrast, in the post-war year of 1946, this figure was up to 124 per cent.

The key point here is that the expansive debt after the World War led to a higher rate of growth due to industrialisation and improvements in productivity and consequently, the debt-to-GDP improved much faster than what was anticipated.

India’s low productivity levels, massive slack in factor of production, especially land and labour along with significant investment opportunities are similar to the conditions that existed in several advanced economies immediately after the two world wars.

This implies that even a higher debt-to-GDP ratio for the current financial year — and for a few more years should not be a constraint on our ability to provide the economy with a growth revival stimulus.

This is of essence as we must recognise the risks posed by an incomplete recovery which could permanently put a ceiling of 6-6.5 per cent on our potential rate of growth.

This will have severe implications for job creation and create several problems due to demographics which would eventually cause social unrest.

At present, nobody knows the extent of permanent damage of the pandemic to global economies but what is well known is that the government needs to step up and play a major role in restoring economic activity to the pre-pandemic levels.

While the present package by the government has done well to restrict the extent of economic damage, it will not be sufficient to revive growth.

Restarting growth would require the government to spend — and spend in a manner that does not deteriorate either the balance of payment or induce inflation.

This becomes important as an increase in MGNREGA wages and other such measures will be permanent drags on our fiscal front and are not advisable.

It is also important to remember that our government has faced several challenges in terms of raising tax and non-tax revenue, which is precisely why any permanent fiscal commitment would be viewed by investors as inconsistent with our medium-term fiscal consolidation plan.

While many may point out at the limited fiscal space available with the government, there are ways in which more space can be carved out without any downside risks to inflation or our external account.

It is important that we prioritise growth at this juncture and doing so requires bold thinking and decision making on part of our policymakers — and that is precisely where it must use the power of 303.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest