Economy

This is No Way to Make Business Easy

The prime minister and finance minister’s pep talks for the industry are not translating into government action to ease barriers for entrepreneurs and remove disincentives for investors.

While addressing global leaders and investors at the Vibrant Gujarat Summit on 11 January, Prime Minister Narendra Modi underscored his commitment to improving the business climate of the country, saying, “Ease of doing business in India is a prime concern for you and for us. I assure you that we are working very seriously on these issues. We want to make them not only easier than earlier; not only easier than the rest, but we want to make them the easiest.”

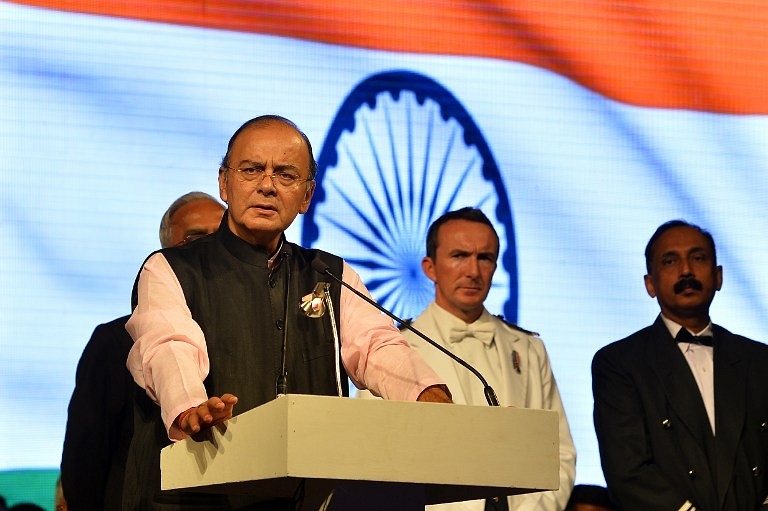

These words, ambitious as they sound, may appear little more than inspired talk to the rational and watchful analysts amongst us. For one, the previous Budget, which was Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s maiden annual financial policy declaration, was quick to mitigate the high expectations held by many quarters. Besides some marginal tax changes and increased government spending, it offered little to none in terms of big-ticket reforms.

Of course, most of the reforms such as diesel deregulation, coal ordinance and liberalisation of FDI in construction and insurance were pushed in the months following the Budget. But then, many of them have failed to manifest on ground. The government’s effort in improving the ease of doing business is one such ‘reform’, the effect of which is conspicuously absent till date.

In a recent report, The Economic Times noted, “75 per cent of new technology start-up firms, ranging from data analytics, mobility and security to cloud that intend to raise seed or venture capital will be domiciled outside the country in 2015.”

According to Sharad Sharma, the co-founder of think-tank iSPIRT quoted in the report, “Three of four new technology start-ups that focus on the global market and plan to raise seed or venture capital will be domiciled outside India.”

This news should come as disconcerting to a government that has spent a bulk of its focus on assuring businesses that things will get easier for them. The news gets even worse when you consider that as much as 40 per cent of India’s employed population works in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). These enterprises also contribute close to 45 per cent of India’s total manufacturing output and accounts for 40 per cent of India’s total exports.

To be sure, the government attended to this issue in the previous budget, albeit not in any productive sense. It announced a fund of funds of Rs 10,000 crore to help different types of raise capital for the SMEs.

The finance minister proposed Rs 200 crore and Rs 100 crore to be set aside for encouraging entrepreneurship among the Dalits and the rural youth respectively. These are merely doles and hardly any different from the subsidies announced for various social schemes.

Plus, there is a strong case to be made for the government to stay out of funding any industrial sector, small or big.

Austrian economist Henry Hazlitt had made the point remarkably when he said,

When the government makes loans or subsidy to a business, what it does is to tax successful private business in order to support unsuccessful private business.

In providing credit to a private business, the government has very few incentives to perform due diligence or investigation to determine whether the funding is being made to the deserving candidate. This is because it uses other people’s money (taxes) to fund businesses as opposed to its own.

Private lenders, on the other hand, use their own money or are directly accountable to the investors whose funds they employ, and hence are far more suited to providing credit to businesses.

This explains why there are not many reasons to be excited about Modi’s credit schemes to small entrepreneurs. On the surface, they may appear glittery. But on the ground, they hardly manifest into visible results. It would be far better had the government were to look at ways of encouraging private investors to invest in start-ups by removing existing barriers to investments. What are some of these barriers?

For one, there is a tax on start-up businesses that has unofficially come to be called as the “angel tax”. It was instituted during the Union Budget of 2012; it is a legacy of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. Essentially, it is a tax that a company has to pay on any fund received by it above the fair market value from an investor.

In very simple terms, if an angel investor provides Rs 25 lakh to an entrepreneur and the fair market value of the business is determined to be only Rs 5 lakh, he has to pay a 30 per cent tax on the remaining Rs 20 lakhs.

What’s worse, the fair market value could be arbitrarily decided by the assessing tax officer — one who has not run or managed any business in his lifetime — at his discretion.

In most cases, the angel investor (who is usually a high net worth individual) invests in a start-up business based on nothing but an idea. This start-up has no sales history, physical assets or goodwill. The investor thus relies on his experience and acute business sense — both of which are absent in the tax officer — to scout new business ideas worth investing in. If he thinks the idea is truly groundbreaking, he attaches a significant premium to it.

Given this fact, if there is anyone, who could possibly know the ‘fair market value’ of the new business, it is the angel investor himself. After all, he risks his own money and, therefore, has incentives to conduct a rigorous check.

The start-up tax levied from new businesses even before they begin operations thus dissuades both angel investors as well as start-ups. Both know that a substantial chunk of the funding will fritter away in taxes and thus will be diverted from any productive use.

Jaitley not only did not revoke this tax in the previous budget, but also instituted another change that was seen as patently destructive for angel investors. Earlier, the horizon for an investment made by an angel investor or private equity fund to be considered long term was one year. This means if an angel investor exited his investment from the start-up after a year, he would be exempt from paying the short-term capital gains tax.

But in the previous Budget, the horizon for an investment to be considered long-term had been extended from one year to three years. This means if the investor sells his investment in the start-up before three years, he will have to pay short-term capital gains tax (which carries a higher tax rate). Additionally, the investor cannot offset losses from one investment against profits from another investment during the same period.

This move is not likely to hurt private equity firms, as most of them remain invested for more than three years anyway. But for angel investors, who are the initial investors in start-ups (even before private equity funds jump in), this change acts as a major disincentive.

It is thus not difficult to see how India’s start-ups are demoralised at their very inception by the regulatory barriers erected by the State. This, even as countries such as Singapore, the United States, the United Kingdom etc offer tax breaks to investors in order to facilitate capital formation.

In its manifesto, the BJP considered the crucial role of the SME sector for the economic development of the country and mentioned that its “overall goal (within the entrepreneurship segment) is to enhance the competitiveness of the SME sector leasing to a larger contribution to our economic growth and employment generation.”

If the government is serious about accomplishing this goal, it must purge the start-up tax immediately and revoke the disincentives that continue to dissuade investors from providing finance to our country’s budding entrepreneurs.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest