Editor's Pick

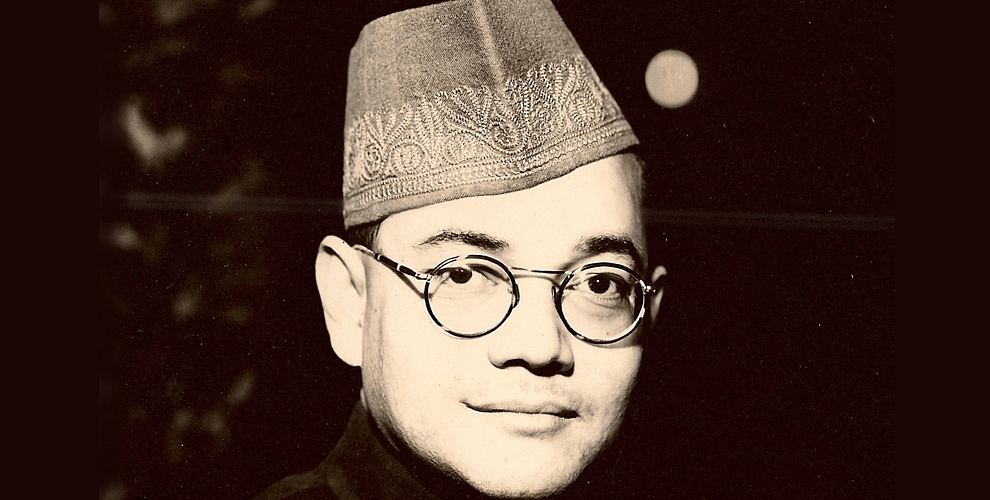

Netaji Records Stay Classified for Fear of Violence

People may have been wondering since Monday what made the NDA government refuse to declassify Netaji-related files that its leaders had demanded when they were in the Opposition. Here are the possible answers. The second part of the Swarajya series on the mystery surrounding Netaji’s death.

Every time the Prime Minister’s Office is approached for declassification of Subhash Chandra Bose-related files through the Right to Information Act, the office’s refusal is couched in phrases that speak of the fear of souring relations with foreign states. But it is the Home Ministry, the nodal agency in the Netaji disappearance case, which has been more forthcoming with some further explanation.

Of course, the ministry did not come out with the explanation on its free will. It had to be nudged into doing it.

In 2006, then Home Minister Shivraj Patil dismissed the Manoj Mukherjee Commission report whose conclusions had rattled the Government of India. The commission had evidence that the story of the plane crash which killed Netaji was a Japanese ploy to give him cover so that he could fly towards the Soviet Union.

Patil made several misleading statements in Parliament to defend the government’s arbitrary dismissal of the report. “Now, you know Japan had fought against Russia or the Soviet Union. Germany had fought a war against the Soviet Union…And even after this, do you think he would have gone to Russia?”

There is enough documentation available today to demonstrate that months before the Second World War came to an end, Bose had been working on a plan.

“In order to destroy our common enemy, Britain, both Japan and the Provisional Government should try every possible means and help each other. Therefore, I earnestly request Tokyo to act as ‘go-between’ and let me approach Soviet Russia,” he told the Japanese according to a document declassified in 1997, now available in New Delhi’s National Archives.

“Once I have been given an interview with the Russian Ambassador, I have perfect confidence in my success in persuading Russia to help our independence movement and at the same time I am sure that I can do something to improve the relations between Japan and Russia, and it might serve to decrease the menace Japan is feeling on the Manchurian side.”

According to a top secret document of 1950s vintage that the government now claims is untraceable, Bose told one of his aides subsequently that “although the Soviets had declared war against the Japanese, it would be desirable to be arrested by the Soviet authorities in Manchuria because we could later negotiate with them and might persuade them to accept us as their friends and not enemies”.

In early 1990s, a Russian scholar (later a witness before the Mukherjee Commission) chanced to see in the KGB archives a letter Bose had written in October 1944 to Yakov Malik, the Soviet Ambassador in Tokyo, seeking the USSR’s support for India’s freedom. The letter bore a comment from the People’s Commissariat of State Security (NKGB) to the chief of the 5th Division of the First Command of NKVD—the forerunner of the KGB. But Indian governments, including that led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, made no serious attempt to access the Russian intelligence archives for this and other records.

Another declassified report reads: “In November 44 there was a general rumour…that SC Bose was preparing to leave for Moscow in order to place all information about the Indian freedom movement before the leaders of the USSR…In December 1944, Lt Sadhu Singh of HQ, First Div, INA, was acting as QM of the YE-U rest Camp, informed B 766 that SC Bose had left for Moscow and was soon expected back in Tokyo.”

In order to get to the bottom of the matter, in 2006, Sayantan Dasgupta, Chandrachur Ghose and I (in a group we named ‘Mission Netaji’) filed a Right to Information application with the Ministry of Home Affairs for certain records about Bose’s fate. The ministry refused to give them to us, and the matter reached the full Bench of the Central Information Commission for a disposal.

In the commission’s final order, available on their site , the ministry stated its considered view in the following words: “…there are 308 more exhibits running into 70,000 pages”.

“That the documents sought under the RTI Act are voluminous and top secret in nature and may lead to chaos in the country if disclosed”.

“The above documents are sensitive in nature, the public disclosure of which may lead to serious law and order problem in the country, especially in West Bengal.”

The commissioners, some of them retired top bureaucrats, were flummoxed by the stand taken by the ministry.

“On the one hand, they (MHA) have reiterated that there is nothing the Government seeks to hide in this respect… On the other hand, they have mentioned that since the documents are voluminous, they need time to examine then and then in the same breath, they say that the documents are so sensitive in nature that if disclosed could lead to chaos in the country.”

So, this is it. The ‘gospel’ from the Raisina Hill about certain Netaji-related records! I find many wisenheimers, many of them Bengalis, giving arguments for not doing anything about the mystery. “Let’s move on, let’s forget about old issues”—the sort of a thing that people first started saying in the good old days of Chacha Nehru.

It is our own Government that is not willing to move on. Indeed there are top secret Netaji-related records with our Government—or at least they were there when Manmohan Singh was Prime Minister—whose disclosure would trigger a political earthquake in India.

This is a problem that Prime Minister Narendra Modi has inherited. But we do not expect him to do a Manmohan Singh on the Netaji matter.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest