From the archives

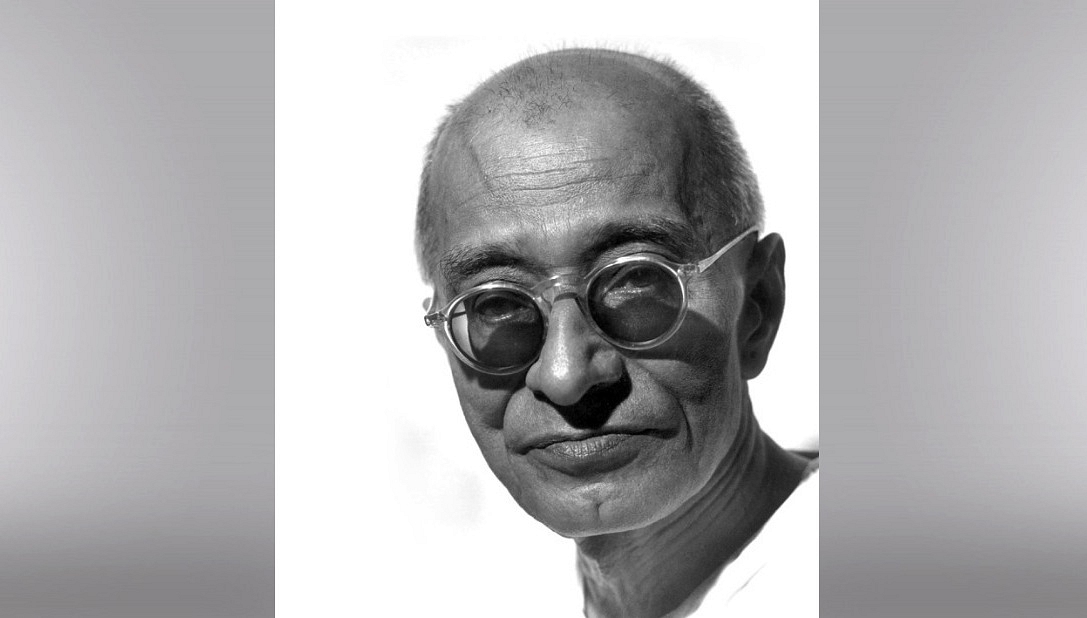

Acharya Kripalani in 1969: Rajaji Was No Friend Of Unregulated Capitalism

- 10 December is the birth anniversary of the scholar, writer, philosopher, administrator and statesman, C Rajagopalachari ,‘Rajaji’. To mark this occassion we reproduce below a tribute to Rajaji written by Acharya J.B. Kripalani in the December 6, 1969 issue of Swarajya. In this piece, Kripalani talks about Rajaji’s contributions to the freedom movement; his career as apolitician and an administrator; and of his deepest convictions.

Rajaji

By Acharya J.B. Kripalani

I salute Rajaji on his ninety-first birthday. He is almost the last of the old guards, under whose leadership we fought the Freedom fight by weapons that injured nobody and nobody was the victor or the vanquisher, but justice was established. Gandhiji taught us that not only must our aims be high but the means of achieving them must be as pure.

Rajaji, then a young lawyer, with a brilliant career at the Bar or the Bench before him, joined Gandhiji at the very commencement of the satyagraha struggle in 1920. It was in his house that, in the small hours of the morning, Gandhiji conceived the idea of giving the call to the nation to commence the truthful and non-violent fight for Freedom, by a nationwide day of fast and prayer. It is on record that this message of Gandhiji reached the remotest corners of India at a time when there were not many newspapers and the radio was unknown.

When in 1921 Gandhiji was convicted of sedition for his article in his paper Young India, entitled “Shaking the Mane of the British Lion”, for six years, Rajaji became the Editor. Since then, with a small interval, he has been fighting battle after battle for his views. It was often said of us, the young people who followed Gandhiji then, by our critics that they unquestionably followed his lead, that they were blind followers. Nobody could say that about Rajaji. As a matter of fact, Gandhiji has said somewhere that Rajaji and myself spoke our minds out frankly.

Not only did Rajaji differ from Gandhiji in his attitude towards Jinnah and the Muslim League, but also from all the members of the Working Committee and the general opinion in the country. Notwithstanding this, Jinnah did not trust him. He suspected a clever trick in the formula Rajaji had evolved for separate Pakistan. This became clear when Gandhiji met Jinnah for talks after his release from the Agha Khan Palace in 1944. During the Quit India Movement, Jinnah did not accept Rajaji’s solution. Rajaji has, in his life, shown that, if convinced of the rightness of the cause he advocated, he would stand by it even if he were alone. It is not unoften that he has advocated lost causes.

When in 1952, Rajaji became the Chief Minister of united Madras after Independence, he wanted and enforced discipline not only in the administration but among the legislators. Often, under the Congress governments, the legislators interfered in the work of the administration. This resulted in corruption, nepotism and indiscipline. He had to resign his office because he introduced basic education which was misinterpreted by his colleagues in the Congress who did not understand the educational problem in India. His opposition to Hindi, though it makes him a little unpopular in what is called the North, has not deprived him of the respect due to him as a patriot, statesman and scholar.

He is a great intellectual of our time, though, like Gandhiji he is not classed as a “progressive” writer, as he does not use communist jargon. He is a powerful writer in English. But he is even more so in his mother-tongue Tamil. He has not only written books on Hindu philosophy but also books for children. His Ramayana has been translated into several Indian and foreign languages.

He is a powerful debater. At the Gaya Congress session, a young man then, he argued his case as a ‘no-changer’ against veteran leaders like Das and Motilal. He did it with such a wealth of argument and eloquence that his view prevailed. Das had to resign his Presidentship of the Congress. It is dangerous to engage in controversy with him. He would often overwhelm the opponent with similes and metaphors. He would also relate stories, real or imaginary, to confuse him. However, it often happens that his arguments though irrefutable, fail to convince his opponents. They feel that he is playing some intellectual trick upon them, which they find themselves unable to refute. Also he rarely loses his temper. If he believed in violence, he would kill his opponent, without a trace of anger appearing on his face.

Today he leads the Swatantra Party which he has created. He believes that in a democracy, reforms can be carried out through “step-by-step”- as the British say, from precedent to precedent. Whatever modernisation maybe introduced in India, must be in the conformity with our age-old values and our culture. He, like Gandhiji, believes that India can only prosper and progress only in the conformity with the genius of the people. That is her national swadharama. She need not mould her life after the fashion of other nations. That way lies danger.

It is said that Rajaji stands for the status quo and for private enterprise. But he is no friend of unregulated capitalism. He believes in free competition when the possibilities are really equal. He is as much against monopolistic capitalism as against monopolistic ownership and management of commerce and industry by the State. The latter can be more dangerous than unregulated capitalistic ownership, which cannot altogether avoid competition. He does not call the present monopoly of various industries and branches of commerce as ‘nationalisation’ but by its proper name ‘Statism’. In the West it is called ‘State capitalism’. He is against the indiscriminate issue of licenses, permits and quotas by which our Government, in its pursuit for power, collects large sums of money to manipulate the elections. This has led to wide spread corruption amongst politicians and administrators.

Rajaji, however does not want chaotic freedom of private industry. He stands for healthy competition under strict supervision of an honest Government working for the welfare of the masses. He does not believe that people can be forced by a Government to be happy. They must seek happiness in their own way, the Government creating favourable conditions for it. What ideas will ultimately prevail in India is in the lap of the future. The present trends are all outlandish. India seems to have lost her soul in imitating others. Not that way does a nation truly build itself. How does it benefit a man if he loses his soul and gains the whole world? This also holds good in the case of a nation.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest