From the archives

From The Archives: Creativity And State Recognition

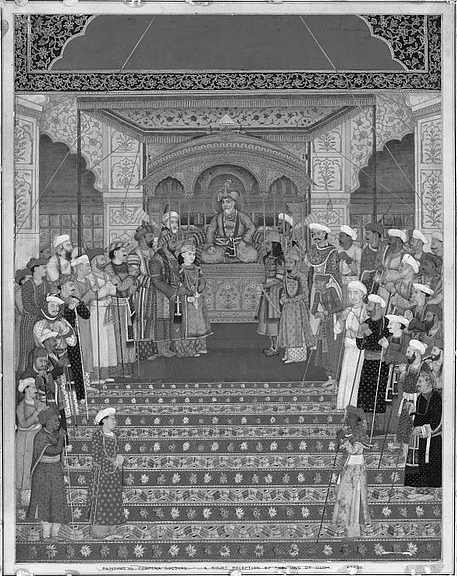

Akbar II in Court

There is a story about a Kullotunga Cola, the conqueror-king, that may not be well known. When the poet Jayamkondar met him for the first time, the king asked the poet where he came from. Jayamkondar replied in a stanza of verse, with great melodic felicity, that he was from Deepamgudi, then a centre of Jain monasticism and Jain scholarship. Impressed by the verse, the king made him the court poet. When Kullotunga conquered Kalinga (broadly now Orissa State) by might of arms, Jayamkondar celebrated the event in a poem justly famous for its dazzling beauties, Kalingattu Bharani.

Royal Patronage

In the good old days, or perhaps the bad old days, for we tend to gild the past, poets flourished because of kings, courts, or patrons of wealth. Certainly, Bhavabhuti and Kalidasa were court poets, though historians may not be certain which Vikramaditya was the discerning patron-monarch. Kamban had Sadayappa Vallal to succour him, and Pugazhendi , Master of the Venba form, had a petty king, Chandran Suvarki to whom he refers with appropriate flattery in Nala Venba. In a Socialist Democratic State, Akademis have to come to the aid of the creative writer, the maestro of Music, the painter who is inspired, the unforgettable dancer. But can the State ever seek out creativity and crown the possessor with laurels, that Time cannot efface?

This is not to scoff at our Akademis, though I must confess their baptism appear to be a Polyglot and strange. I plead guilty to having been the President or Chairman of a State Akademi concerned with the due recognition of Music, Drama and Dance for three years or more. Only the abuse of my telephone by society ladies anxious to secure grants or provisions of undeserving artistes, whom they keenly wished to succour, proved the fly in the ointment. The office was otherwise enjoyable for aesthetic pursuits have engrossed a great part of my leisure. Nor do I intend the slightest sarcasm, with regard to the most erudite and scholarly persons who actually hold such offices in Akademis, whether at State or Union levels. They deserve and have my respect. But I am on a far deeper and more subtle issue.

By definition, the State is not a persona (except in jurisprudence) and cannot be a Harsha or Vikramaditya or Akbar or even Jehangir. Harsha was a dramatist of some distinction, Mahendra Varman Pallava was both creative and a great Rasika, indisputably Swati Tirunal was a fine Sahitya Karta, and composer. Can a democratic State ever seek out and discover true creativity which may be smouldering in some despised corner, or flaming angrily in poverty, drunkenness or a slum? Does not the State merely crown with laurel (acrimonious controversies apart) some brow already crowned by recognised achievement, and even these laurels, may the not fade very quickly? Of course, there are fortunate exceptions, but I do assert that they are not detractions from the thesis.

True creativity, inspiration, is the strangest goddess. Even time, cannot always and unalterably, set a signature upon her visits. Even the most prestigious prizes that the world can offer may tempt her only to a scornful smile. Affluence may not bar her courtship, nor stark poverty, degradation, torturing illness. Tagore, whose mini-biography I have been reading, had his share of tribulations, but was born with a silver spoon, and never worked for his livelihood. When Barathi died in Triplicane (and this is one of my memories of boyhood), there was no cash in the house for poor Mrs. Chellammal Barathi to pay for the cremation expenses.

To proceed further afield, Francois Villon was a proclaimed thief, and narrowly escaped hanging. He has written some of the most marvellous Ballads in world literature. Gauguin died in utter poverty and ill-health. Chatterton committed suicide in his teens – it was sheer malnutrition. As Browing wrote – “What porridge had John Keats?” Tennyson, adored while alive suffered utter eclipse and even contempt, after his death. Thanks to Elliot, Harold Nicolson, et al, we now rightly feel that in many passages, he was a great poet.

Even the Nobel Prizes for literature make dismal, disquieting reading. Tolstoy was passed over for some one now forgotten. Kipling was crowned when Meredith was alive. Who remembers Selma Lagerlof, Knut Hamsun? I do feel that we should not have heavy cash prizes that are fortunes of, for the recognition of art form of aesthetic-creative achievements. The blessing may shroud a curse; the worst impact may be on the awardee himself. It profits nothing that you gain the whole world, if you thereby lose your soul. I think of those most noble lines of Boris Pasternak, commencing “It is not seemly to be famous”.

"To give yourself, this is creation,

And not defean or eclipse,

How shameful, when you have no Meaning,

To be on everybody's lips!"

What is the moral that we should not have Akademis awards? Certainly not. Akademis, however baptised, are essential, for poverty, lack of leisure, the bondage of hack-work, do tend to blight creativeness. The goddess may well triumph over any terrestrial obstacle, but that is no ground for neglect of the Artiste. Pensions for those who have achieved something that has a glow or splendour, and who are in dire need, are really a form of enlightened investment. But I feel that the best kind of Akademi is like the Academy of France, self-appointed, self-crowned, autonomous. It is true that Paris also seethes with politics, the curse of our times, and I read that De Gaulle stood in the way of a great writer for years. I have relished several of our Sahitya Akademi publications, but it is reported that many publications or Award-books, cumber the shelves unsold. This may well be a Non Sequitur, for Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads did not sell either. But there it is.

Living is both marvellous and intricate, and does not easily admit of crude generalisations. This is why Morality is a fragment, Ethics lags behind the complexities of our feelings, and a prostitute in Dostoevsky may be touched by a noble flame, unknown to the most chaste heroine of an insipid Victorian romance. In writing all this, I have really no moral to offer, for, to draw a conclusion is to stop being meditative. Creativity is the strangest of phenomena the democratic State, as a discerning Patron of Arts, must have the humility to recognise that Harsha, Mahendravarman Pallava, Kulottunga Cola, or Swati Tirnal had far greater genius advantages in hailing at sight the true flame of genius.

This article was authored by M Anantanarayanan (Former Chief Justice, Madras High Court) and was published in the 5 March 1977 edition of Swarajya.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest