From the archives

Srinivasa Ramanujan – The Man Who Knew Infinity

- A brief biography of Srinivasa Ramanujan from our archives, written by M S Kalyasundaram for the 26 April 1958 edition of Swarajya.

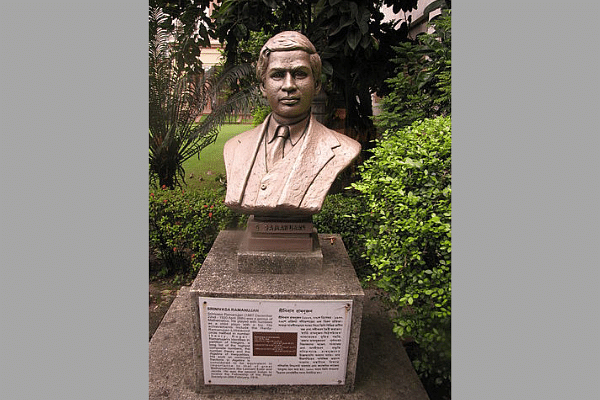

Bust of Srinivasa Ramanujan, Indian mathematical savant, in the garden of Birla Industrial & Technological Museum (AshLin/Wikimedia Commons)

On the 26th of April, thirty eight years ago, a great light went out. That light was a mathematical wonder, answering to the name of ‘Ramanujam’. In his, “Men of Mathematics”, E. T. Bell writes of him :

“When a truly great one like the Hindu Ramanujam arrives unexpectedly out of nowhere, even expert analysts hail him as a gift from heaven: his all but supernatural insight into apparently unrelated formulas reveals hidden trails leading from one territory into another, and the analysts have new tasks provided for them in clearing the trails.”

Ramanujam was the son of a poor clerk – Srinivasa Ayyangar, working in a cloth-dealer’s shop in Kumbakonam. His mother was from Erode – which has some significance for this narration. Goddess Namagiri of Nammakkal in Salem district nearby, seems to have had a mystical influence over him. He often explicitly stated that he saw solutions to difficult problems and also the final forms of fundamental theorems- to be filled and justified later – in dreams inspired by Namagiri Devi.

Ramanujam was born on 22nd December, 1887. Contrary to certain popular reports, he showed evidence of all-round merit quite early and won a studentship.

While he was in the second form he posed the question, “What is the ultimate truth of Mathematics?” While yet in the lower forms, Ramanujam mastered Progressions and Trigonometry. B.A. students used to take their difficulties to him. But it is doubtful if his rapid intuitive approach was of help to them. A shock was in store for him when some magnificent work of his was found to have been discovered and published by the great Euler, more than a century back·

Ramanujam stowed away his papers under the tiled roof in his house and kept on. When he was in the sixth form, a copy of Carr’s synopsis of Pure Mathematics was lent to him. He solved all the new and difficult problems without the help of other books or teachers, inventing new techniques as he marched along. Prof. Hardy has recorded that it was a book of no great value but has become immortal by having opened rich vistas to Ramanujam’s strange and hungry mind.

Ramanujam passed his Matric creditably and joined the F.A. class with a ‘Subrahmanyam Scholarship’. But during that year he lost himself so much in mathematical research that he neglected the other subjects and failed in the Junior F.A examination and, consequently, lost his scholarship.

Then came a period of depression and frustration and, on top of it, bad advice. Nothing is known of what he did in that period of wilderness except that he wandered right into the Telugu districts. But,all the time his stout notebooks were being filled with his findings.

In 1909, his marriage took place and it became necessary for him to settle down and earn a livelihood.With the help of Dewan Bahadur R. Ramachandra Rao, he secured a clerical post in the Madras Port Trust office.

Ramanujam’s work began to appear in the Journal of the lndian Mathematical Society. He was encouraged to send some of his findings to Prof. G.H Hardy, Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. His first letter, vetted crudely by his well-wisher pointed out an error in a statement published by Hardy! Hardy sensed a genius at once and suggested that Ramanujam go over to Cambridge without undue delay, but religious scruples stood in the way.

Finally, Ramanujam got his mother’s permission to travel overseas and the Madras University again rose to the occasion and sanctioned a scholarship of $250 tenable for two years, as also grants for traveling, outfit, and so on. The period was later extended to April, 1919. Ramanujam arranged with the university that Rs 60 be remitted out of it every month to his mother.

He reached Cambridge and got a place in Trinity college. The college supplemented his scholarship with $60 per annum. Professors Hardy and Littlewood became Ramanujam’s teachers and filled the gaps in his self-acquired knowledge. But both of them repeatedly and graciously admitted that they learnt a good deal from him, and considered association with him an extraordinary piece of good fortune for themselves. Hardy has written that he was “afraid of destroying Ramanujam’s spell of inspiration” and of his “profound and invincible originality…the flow of which showed no signs of abatement”.

Vital work filled Ramanujam’s notebooks and flowed into the best of European mathematical journals, and triggered off others’ works. Great was the praise showered on him repeatedly.

But, in May 1917 his health showed signs of failing. Tuberculosis was suspected. But he could not leave for the warmth of his homeland with a war on. February of 1918 brought heartening news. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society(F.R.S), the first Indian to be so honored. He was only 30 then.

In October of the same year, he was elected a Fellow of Trinity college, Cambridge. It was a coveted honor. It carried a fellowship of $250 per year for a period of six years, with no duties or condition attached.

The Cambridge University also suggested to the Madras University to make Ramanujam free for life from economic cares. The Madras University extended his scholarship by five years, undertaking to meet all his travelling and other expenses incurred in the cost of mathematics and even contemplated, on the advice of Prof. Littlehailes, creating a Professorship for Ramanujam.

But fate laughed at these generous plans. Ramanujam reached Madras in April, 1919. The best medical men in the city did their best to save him. But he passed away on 26th April 1920, survived by his wife and parents. He had no children.

Even when he was writhing with pain, he worked in bed, till four days before his death.

Prof. Hardy has recorded that simplicity, humility, gratitude for the least suggestion received from co-workers were Ramanujam’s charactersitcs, and that ‘F.R.S’ sat lightly on him.

In the last letter which he wrote to the Madras University before leaving England, he evinced great sympathy for poor students and revealed his plans to help them “as the total amount of money to which he would be entitled would be much more than he would require in India”.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest