Ideas

Assam Fallout: Time To Experiment With Dual Citizenship Categories

- India should not be squeamish about taking the lead in Citizenship Act changes.

- The world will follow, for there is no escape from demographic reality and constant fears over identity threats.

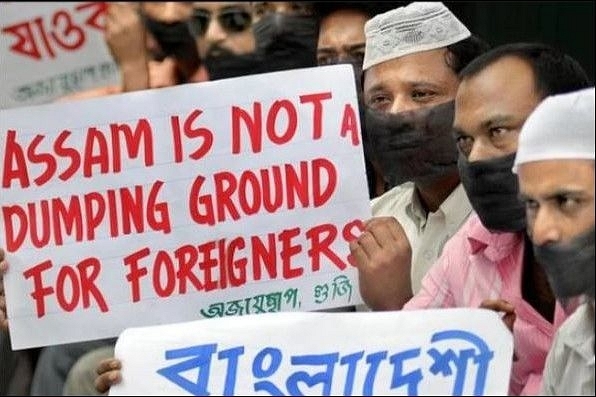

People in Assam protest against the settlement of illegal immigrants in the state. (Daily Sokal)

It is interesting how, in just a matter of weeks, the entire media discourse over illegal migrants in Assam has changed. In fact, suddenly there is concern over all north-eastern identities.

In the second half of 2018, the big media story from the North-East was the National Register of Citizens (NRC). The media outrage was about how the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was trying to make four million people stateless, as this was the number of people who had not been able to prove their claims to having lived in or entered Assam before 1971 in the final NRC draft. The media highlighted stray cases of genuine citizens who were left out in the draft to hint that almost nobody was an illegal migrant.

Now, with the BJP-sponsored Citizenship (Amendment) Bill halfway through (the Lok Sabha has passed it, but the Rajya Sabha may well demur), the conversation is suddenly the exact opposite: about how the bill will allow Bengali migrants, especially persecuted Hindu and other minorities, from Bangladesh to claim citizenship in Assam and other states of the North-East.

The argument now is that the bill, if passed by the Rajya Sabha, will undo clause 6 of the Assam Accord, which says that “constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards, as may be appropriate, shall be provided to protect, preserve and promote the cultural, social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people”.

The double-think involved is this: to fulfil the promises made in clause 6 you can do positive things like promote Assamese culture and language, even while incorporating political and social safeguards in the Constitution. It does not require the mass deportation of illegal immigrants, especially those who faced persecution in Bangladesh. Clause 6 is not necessarily in conflict with the Citizenship Amendment Bill, but to the average Assamese, or even the wider north-eastern population, it is the physical presence of a large number of Bengalis that seems threatening to their culture. They want most of them physically out.

Clearly, there is a problem with the timing of the Citizenship Amendment Bill, as it seems to negate the deportations promised under NRC. Logically, it should have come after the NRC process was completed, and the Assamese had seen substantial numbers of illegals either deported to Bangladesh, or offered alternative residencies in other states. This is what has created a complication that will cost the BJP dear. But the BJP must be complimented for the courage it showed in trying the push the bill through, despite bogus 'secular’ opposition to it. It has kept the faith with its core base even at the cost of losing out in the North-East, where it has built a formidable political presence over the last four-and-a-half years.

However, the lesson to learn is not that the bill is wrong in terms of intent or content, but that the whole concept of citizenship needs re-examination when ethnic identities are under threat not only in the North-East, but almost anywhere in the world. Whether it is the US, or Europe or many other countries, local populations are entirely uncomfortable with mass migration that tends to change demography irreversibly. The only three places which have escaped the turmoil are China, Japan and Korea, which do not allow even limited immigration.

Since identity matters to everybody, but immigration is also needed to bring in workers who are willing to do jobs that the locals won’t, the world needs to reconsider the whole concept of citizenship laws in this context.

The current assumptions underlying most citizenship laws are the following:

One, all residents who become citizens ought to be treated equally under the law. It need not be so: we can have two types of citizenships, with different entitlements under the law.

Two, any child born in any country, even assuming its parents are illegals or non-citizens, automatically is entitled to citizenship. This can be made conditional in future.

Three, residents who have spent a certain number of years working or living in a country are automatically entitled to citizenship through a process of 'naturalisation’. This need not be the case at all. Work permissions and residency permits can be delinked from full citizenship or entitlement to one.

The above principles need to be challenged in a world where ethnic, religious, linguistic, and national identities are under threat not only by illegal migration, but also legal ones; by demography (higher birth rates, etc) as much as technological and other changes. Migration can be caused by both push and pull factors. The push factor could be persecution and poverty (as in the case of Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Afghan Hindus and others), or the pull factor (even better livelihoods and wages in a more prosperous country, as is the case with Indian IT workers in the US).

It is foolish to believe that migrations can be reversed without force and violence. This is unsustainable and inhuman. However, it is equally foolish to obfuscate issues relating to identity and political power shifts caused by unlimited migration.

Citizenship laws need to address these challenges by moving away from their own earlier assumptions. So, on the one hand, countries that want cheap labour through immigration (the US, Europe, India), should grant easy residency and work permits, but with the clear understanding that work permissions cannot ever be converted to citizenship or the right to vote. This way the ethnic and political demography does not change adversely for the locals.

Citizenship need not be automatic for new migrants even after a process of naturalisation. This means a whole lot of conditions should be met – including fluency in the language, respect for the local culture, and a willingness to abandon key aspects of the immigrant’s previous social mores – before citizenship can be granted. Mere birth in a country should not be an entitlement to citizenship if your parents were not citizens. Even here, conditions can be imposed. The right to stay, study, marry and work can remain, but citizenship will follow only after conditions are met.

It is worth recalling that when the Parsis settled in southern Gujarat after fleeing persecution in Islamic Persia, three conditions were imposed on them for being given refuge by a local prince: they had to speak the local language, follow local marriage customs, and could not carry arms. In exchange, they could practice their religion freely and manage their community affairs autonomously.

There is no reason why similar conditions should not be imposed on immigrants to any country in the twenty-first century. In India, for example, the conditions could include compulsory learning of the language of the state of domicile, formal respect for all Indic religions and traditions, and non-involvement in any kind of religious conversion activities.

In the case of illegal migrants to Assam, since deportation of persecuted Hindus and Bangladeshi minorities is unconscionable, and the deportation of Muslims is not feasible, the logical thing to do is to disenfranchise the latter while granting them work and residency permits. We can fast-track citizenship for those who can never return to their home nation (Bangladesh). Conditions can be imposed even on this group with regard to compulsory learning of Assamese (for those who stay there), and Hindi or Malayalam or Tamil if they are shifted to other states.

Proselytising activities by all such immigrants should be banned, and breach of this promise should involve cancellation of their citizenship rights. Equal citizenship rights can be given in the next generation.

In Assam, the threat to ethnic identities is compounded by changes in religious demography too, with Muslims now accounting for 34 per cent of the population. This is a tipping point from where the Muslim voice in power can only get stronger. One can safely predict that huge political and social upheavals loom large if local identity concerns are not addressed.

India should not be squeamish about taking the lead in Citizenship Act changes. The world will follow, for there is no escape from demographic reality and constant fears over identity threats.

Liberals may demur and claim that individuals have many identities, but this does not mean some identities do not matter more than others. As long as humans cherish the idea of preserving and protecting broader group identities, citizenship rules have to address the issue.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest