Ideas

Is Christian Conversion Missions in India, Social Reform? The case Of Pandita Ramabai

- Humanities education in Indian universities is a minefield of prejudices with its discourse around the Hindu society couched in the language of nineteenth century missionaries, like Pandita Ramabai.

- It’s important to put Indian civilisation, its culture and tradition in the right perspective.

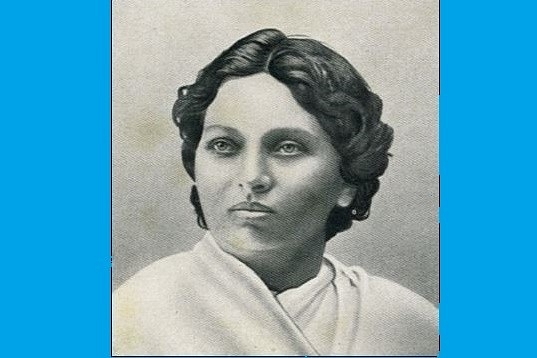

Pandita Ramabhai

While many of us may not be aware of Pandita Ramabai, she has a pervasive presence in the Indian academia. The life of Pandita Ramabai is featured in National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) text books and is studied in depth in the postgraduate humanities courses. These academic texts variously describe her as a social reformer, the first Indian feminist, and an icon of women’s education.

Marxist historians and Christian missionaries have written hagiographical tomes glorifying her as the champion of women’s liberation, applauding her effort to dismantle ‘Hindu patriarchy’ and “Brahmanical hegemony”. In a certain postgraduate class at the University of Mumbai, students are taught that Ramabai converted from a religion whose dharma shastra considered women “worst than the ghosts and spirits” to the “gender egalitarian impulse of Christianity and its compassion to sinners.”

So, who is Pandita Ramabai and what is her contribution to the Indian society? Born in 1858 in a Brahmin family, Ramabai was conferred the title of ‘Pandita’ at the age of 20 by the Calcutta senate for her proficiency in Sanskrit. Widowed at 22 years, she started an organisation Arya Mahila Samaj to promote the welfare of women. The following year, she went to England for higher studies and during her stay there, formally converted to Christianity under the Anglican Church of England. After a few years in England, she travelled to America to solicit funds for starting a residential school for high caste Hindu widows.

During her fund-raising campaign she authored the book, The High Caste Hindu Women to highlight the plight of Hindu women. This work is hailed by the academia as the first “Indian feminist manifesto”. Citing Manu Smriti, “the greatest authority next to Vedas”, Ramabai brings to fore the condition of Hindu widows in the most sordid manner. She described Hindu widows as someone “sacrificed on the unholy alter of an inhuman social custom…crushed under a fearful weight of sin and shame, with no one to prevent their ruin” and the need “to rescue the little widows from the hand of their tormentors.”

No rhetorical device was left unused to implicate Hindu texts and its traditions for the condition of Indian women. While purporting to be objective, she produced an atrocity literature par excellence, following the template of nineteenth century missionary writings on India. She wrote that the Rajput men kill their girl child as easily as “destroying a mosquito or other annoying insect” while a “Brahman of a high clan will marry ten, eleven, twenty or even one hundred and fifty girls.” The practice of sati was described in all its gory details, and the Brahmins were held responsible for its propagation

After painting this repugnant picture of the Indian society, she revealed her missionary agenda. In her words, “I believe that those who regard the preaching of the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ to the heathen so important as to spend in its accomplishment millions of money and hundreds of valuable lives will deem it of the first importance to prepare the way for the spread of the gospel by throwing open the locked doors of the Indian Zenanas (homes).”

And how will the locked door of Indian zenanas be opened for the spread of Gospel. She wrote, “(By) giving education to the women, whereby they will be able to bear the dazzling light of the outer world and the perilous blasts of social persecution.”

Two remarkable elements stand out – first, even in the nineteenth century, the Americans were sending millions of dollars to convert the “heathens” (these millions have increased to billions in the twenty-first century) and secondly, how the education of “heathen” women in missionary schools is the first preparatory step for the eventual conversion to Christianity.

(Few years later Swami Vivekananda in America would come under attack from Ramabai’s American supporters for giving a more sympathetic account of Indian society. To such canard, an anguished Swami Vivekananda wrote to his friend, “I am astonished to hear the scandals the Ramabai circles are indulging in about me. Don’t you see Mrs. Bull, that however a man may conduct himself, there will always be persons who invent the blackest lies about him? At Chicago I had such things every day against me. And these women are invariably the very Christians of Christians!”)

Missionary Activity In India

In 1889, she started Shanti Sadan in Mumbai as a religious-neutral residential school for high caste widows. However, from the very beginning, the school ran into controversy as her covert proselytising activity became known. With reports emerging of rampant conversions, the shocked guardians withdrew their girls from the school. Undeterred, Ramabai, redoubled her proselytising mission. She later relocated her school to Kedgaon (near Pune) and rechristened it as Mukti Sadan, to fully highlight the missionary character of her institution.

Inspired by numerous revelations and visions of the Holy Spirit, Ramabai coveted the “spiritual children” through conversion. Once, while converting 15 girls to Christianity at a mission camp, she “offered thanks to the Heavenly Father for having given me fifteen children, and I was, by the Spirit, led to pray that the Lord would be so gracious as to square the number of my spiritual children before the next camp meeting took place.” Six month later she had her “225 souls”.

Her greatest success in missionary effort came during the famine years of 1896-1900 in Maharashtra and Central India. She housed a few thousand famine-stricken orphan girls and widows of minor age, who were then baptised enmasse to Christianity and their faith ‘strengthened’ through a controversial method called revivals.

During these revivals, the Holy Spirit descends on the group of praying women, and manifests itself in physical sensation of burning, speaking in different tongues, loud clamour, prophecies, healings and miraculous signs. These rapturous manifestations are ‘evidence’ of the outpouring of the Spirit. Thousands of minor girls were baptised and went through such “revivals” at her mission house. Such manifestation of the Spirit for the “first time in India” was hailed by Christian organisation across the world.

Meanwhile, Ramabai ‘s desire to gain “spiritual children” during the time of famines was unabated. One of the financial backers of Ramabai’s mission, Alexander Boddy of Anglican Church, commented that the famine situation in India presents, “great opportunities and great difficulties to the brave band of workers at Mukti.”A missionary at Ramabai’s mission wrote that “a good number of the ablest and most heaven-blest workers for Christ in India, were once famine orphans.”

Proselytising during the time of natural calamity is a well-known missionary activity. It is easy to harvest souls when the target is vulnerable and in dire need of help. Ramabai was probably the first missionary in India to apply this tactic successfully on such a mass scale. Bal Ggangadhar Tilak was furious with Ramabai’s method of converting famine-stricken orphans and widows by preying on their helplessness. He described the Mukti Sadan residents as “widows caught in Ramabai’s net during the unique opportunity of the famine years”.

Funds flowed from across Europe and America to support her conversion missions. Such was the financial clout of her mission, that she regularly sent financial support to missions in Korea and China. The Anglican Church considered Ramabai, a former Brahmin woman, as an invaluable resource to proselytise among the upper caste. She was, according to them, “one of India’s daughters whom we hoped God was training to carry a ray of light back to that benighted land.”

Ramabai’s proselytising activity amongst young girls continued for 33 years before she passed away in 1922. In the process, she created many more Ramabais. Her mission house became a hub of producing “Bible women”, where the girls would receive “a thorough training for some years”, after which they would “go out as teacher or Bible women to work in different mission.”

Ramabai started her public career with an initial impulse to work for the welfare of widows but later became a fundamentalist missionary, with the goal of having as many “spiritual children” as possible. The vulnerable famine-stricken orphans and widows of minor age come to her residential school in good faith, not knowing they will be coerced into converting to Christianity through controversial means of Holy Spirit ‘revivals’. Her fundamentalism led her to re-translate the entire Marathi Bible to rid it “of certain words which express idolatrous ideas”.

Now the question is why does Indian academia call her fervent missionary effort as social reforms and that too in such hagiographical terms? Does the NCERT and humanities department believe that withdraw women from Hinduism is social reform? Is the term ‘social reform’ only applicable when the target of ‘reform’ is Hindu society?

It’s shocking that the entire academic discourse around Hindu society is couched in the language used by nineteenth century missionaries (which were later picked up by Dr B R Ambedkar). The Indian academia, it seems, has internalised the missionary critique of Hinduism and has taken upon itself to highlight the ‘evils’ of this ‘benighted’ religion. Humanities education in Indian universities is a minefield of prejudices, and to emerge from its academic trenches without developing a profound aversion towards Indian civilisation – its culture, its traditions, its worldview, its philosophy – is well-nigh impossible.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest