Ideas

The Real Challenge Of Defining Hindu Rashtra, From Ambedkar To Savarkar

- Any past or future idea of Hindu Rashtra must emerge from a sense of a sacred geography, which is what Savarkar was beginning to outline in his work on Hindutva.

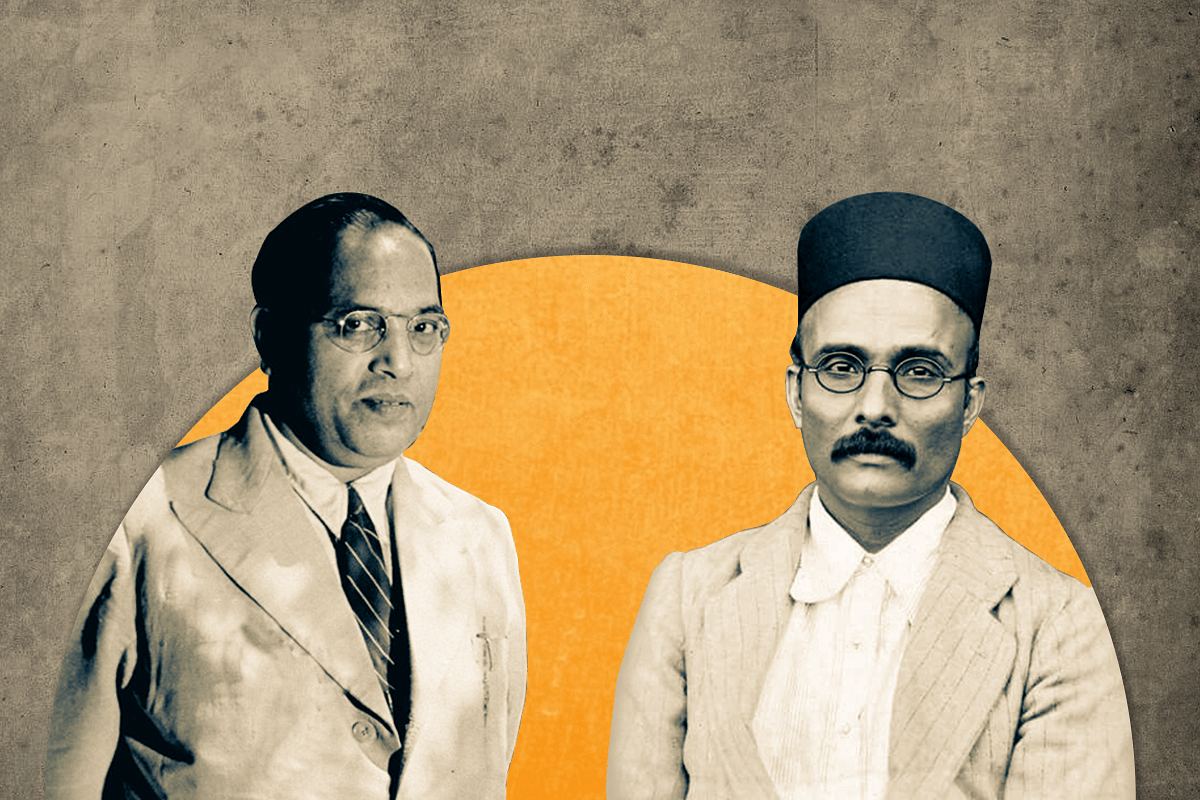

B R Ambedkar and V D Savarkar

One problem with the idea of a Hindu Rashtra is that it is simply undefined even as an idea or ideal. Those who want one are not clear on what a Hindu Rashtra would mean for the citizens of India.

Those who are against the idea are not sure why they dislike it. But they are happy to demonise it, both by linking the worst behaviours of some Hindus or Hindu organisations, or by summarily rejecting it as it would mean India becoming a “Hindu Pakistan” – a theocratic state that defines itself too narrowly and uses violence to impose religious ideas on the whole population which may not be so inclined.

In a recent column in Hindustan Times, Vir Sanghvi, one of India’s best writers in English, including on the subject of food, challenged the votaries of Hindu Rashtra to give us a “what-if” book on what India would have been like if we had become a Hindu nation right at the outset in 1947.

Among other things, Sanghvi points out the problems India would have faced if it had defined itself as a Hindu Rashtra. Among the questions he throws at us are the following: What would Partition have been like? (that is, would we have had more two-way religious migrations if India had declared itself a Hindu Rashtra in 1947 itself?)

What kind of government would we have had? Would we ever have had a claim to Kashmir? Would we have followed a radically different ideology? Would minorities have been second-class citizens in a Hindu Rashtra? What about the North-East? What about the Sikhs? What would happen to caste? Where’s the book (explaining what a Hindu Rashtra would look like)?

Sanghvi has done Hindus who demand Hindu Rashtra a service by asking these questions. But, as we shall see, these are not questions emerging only because a “Hindu Nationalist” Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is in power. Many of these questions were raised as far back as in the 1940s, including by Babasaheb Ambedkar in his monograph on Pakistan, where he agreed with Mohammed Ali Jinnah that Muslims did deserve their own country.

He also pointed out some of the illogic in V D “Veer” Savarkar’s own definition of Hindu Rashtra and Hindutva, and how Muslims should be treated in an undivided India.

The funny thing is he did not raise these questions about other minorities like Christians, even though Christianity is motivated by similar divisive impulses. Even in the last few decades, Christian southern Sudan was separated from Muslim Sudan; Cyprus was divided along religious lines; largely Christian East Timor got independence from Muslim Indonesia. In India, the Christian majority states of the North-East have always nursed a separatist streak, often aided by the church.

But partition or no partition, the questions raised by Ambedkar, and now Sanghvi, cannot be ducked any more.

It would be apt to begin the discussion on Hindu Rashtra by first dealing with the Ambedkar-Savarkar disagreement in the 1940s.

Ambedkar pointed out, not unfairly, that both Jinnah and Savarkar agreed that Hindus and Muslims were separate nations and the only question was whether the country should be divided along religious lines or function separately within the same unified state.

It is worth quoting Ambedkar’s criticism of Savarkar’s position at some length, especially his conclusions.

He writes:

Ambedkar praises Savarkar’s position as bold and clear, something the Congress wanted to obfuscate.

He writes:

But Ambedkar is scathing in his rebuttal of Savarkar’s idea of a unified India, where both Hindus and Muslims lived as separate entities. He said this was illogical, inconsistent and even “dangerous” for the new country.

He wrote:

The above paragraph suggests that when two “nations” – a term defined by Ernest Renan, a nineteenth century French Orientalist – live in one territory, it needs violence and coercion to create one nation out of two. Ambedkar thus criticises Savarkar for being wishy-washy about his idea of a Hindu India.

“Mr Savarkar adopts neither of these two ways. He does not propose to suppress the Muslim nation. On the contrary he is nursing and feeding it by allowing it to retain its religion, language and culture, elements which go to sustain the soul of a nation. At the same time, he does not consent to divide the country so as to allow the two nations to become separate, autonomous states, each sovereign in its own territory. He wants the Hindus and the Muslims to live as two separate nations in one country, each maintaining its own religion, language and culture. One can understand and even appreciate the wisdom of the theory of suppression of the minor nation by the major nation because the ultimate aim is to bring into being one nation. But one cannot follow what advantage a theory has which says that there must ever be two nations but that there shall be no divorce between them. One can justify this attitude only if the two nations were to live as partners in friendly intercourse with mutual respect and accord. But that is not to be, because Mr Savarkar will not allow the Muslim nation to be co-equal in authority with the Hindu nation. He wants the Hindu nation to be the dominant nation and the Muslim nation to be the servient nation. Why Mr Savarkar, after sowing this seed of enmity between the Hindu nation and the Muslim nation, should want that they should live under one constitution and occupy one country, is difficult to explain.” (Sentences in bold are mine, not Ambedkar’s)

However, while Ambedkar is right to point out Savarkar’s inconsistencies and contradictory logic, one should also question what Ambedkar was advocating: basically he was saying that a nation can be forged only through violence (see sentences in bold above), and thus a Hindu Rashtra could have come into being only by suppressing Muslims and their sense of nationhood.

In many ways, thus, Ambedkar was more extreme than Savarkar on the Muslim question, but also off the mark. His views came entirely from the Renan definition of “nation”, which is rooted in the idea of a people with a common memory of joint struggles and staying in a well-defined geographical area that is defensible and separate. In short, this is the Abrahamic, Westphalian idea of the nation-state that evolved in Christian Western Europe, and where geography aided such nationalisms.

In India, several “nations” (as defined by Renan) have existed in the same state, and several “states” have existed separately but whose people have shared a common sense of “nationality”. Here nationality is defined as sharing a common cultural sensibility and a shared sense of “A sacred geography” (the title of a book by Diana Eck on India). India’s sense of nationhood is civilisational in character rather than a Renan equivalent of the nation-state.

Looked at more closely, Savarkar’s sense of a unified India dominated politically by Hindus is not as outrageous as it seems. This is how countries like Malaysia (where the Malays dominate, but Hindus and Chinese have subordinate voices) and Singapore (with the Chinese on top, with Muslims and Hindus in subordinate roles). The Savarkar vision of Hindu Rashtra would thus have resembled Malaysia or Singapore, both successful countries today.

In India, the closest we come to such an arrangement is Kerala, where politics is religiously delineated, with strong Muslim and Christian parties pushing their agendas. What is missing is Hindu domination at the top, as Hindus are represented by weak caste-based parties (the Nairs and Ezhavas have their own parties). In short, Kerala is the opposite of what a Savarkar would have wanted, by allowing the minorities to rule like the majority.

The problem is Congress secularism, as Ambedkar himself pointed out in his tract on Pakistan. Ideally, the Congress should have been a Hindu party at the top of a coalition of other religious parties, but it has turned out to represent nobody in the end. Is it any surprise that for two successive elections it has been reduced to the size of a regional party?

Coming back to the idea of Hindu Rashtra, Ambedkar accepted the Renan, Westphalian sense of nationhood, ignoring the more nebulous – but more appropriate – Indian notion of nationhood that is civilisational in nature. Thus, any past or future idea of Hindu Rashtra must emerge from this sense of a sacred geography, which is what Savarkar was beginning to outline in his work on Hindutva. The work of defining Hindu Rashtra is still incomplete, and one hopes we will be able to get a clearer picture of not only what it is, but what it should be as we proceed with this series.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest