Magazine

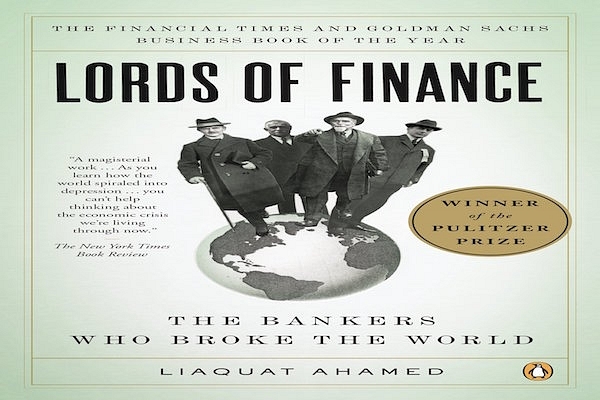

Book Review - Lords Of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke The World

- The book details the personal histories of four central bankers who faced the twentieth century’s toughest economic crisis

Image Credit: Amazon

Published in 2009, Lords of Finance won the FT Best Business Book of the Year award. Seven years later, it remains relevant for understanding the challenges of managing debt, de-leveraging and avoiding a global economic depression. The book, of course, is not fiction. But, it is as fascinating and gripping as a thriller.

Lords chronicles the turbulent economics of the world between the end of World War I and the commencement of World War II. It lets us peep into the lives of four men who governed the most powerful central banks of that time—Benjamin Strong at the Federal Reserve, Montagu Norman at the Bank of England, Hjalmar Schacht at the Reichsbank in Germany, and Emile Moreau at the Bank of France.

Schacht, who was sent to jail for his association with the Nazi party in its early years, dissociated himself well before the Nazi atrocities began. Nor did he agree with their economic policies. He laid the foundation for German hyper-aversion to inflation. To a large extent, he deserves to be credited for extinguishing German hyper-inflation.

Reminding readers of the relevance of the past to the present and the future, the book underscores the cyclical nature of history as most Indic philosophies would tell us. Life and history are not linear. The US was permanently scarred by the Great Depression. The scars hurt even today. Who would want to relive a 50 percent plunge in the index of industrial production, a 25 percent unemployment rate and 4,000 banks failing in one year?

For Ben Bernanke, the scholar who had studied the Depression in depth, the global crisis of 2008 was the ideal stage to test out his theories. As Chairman of the Fed, he unleashed liquidity abundantly. Though a menu of alphabet soups, it worked. The worst effects of the Great Depression were avoided. Neither production nor employment plunged as much as they did in the 1930s. Nor were there so many bank failures. After two to three quarters of funk, economic activity resumed from the summer of 2009.

Bernanke shares his first name with Benjamin Strong, one of the four central characters of Liaquat Ahamed’s classic. Strong died in 1928. Ahamed notes that he would have handled the unfolding economic crisis in the 1930s far differently and effectively than his successors did. But that is a good situation to be in. It is good to be missed on stage than to be present and disappoint one’s fans and observers.

The measures that Bernanke put in place in 2008-09 have continued long after the crisis has abated. Indeed, they have been expanded further. Perhaps, that is where the modern central bankers have departed from the four “lords of finance”. Ahamed’s heroes might have been uncomfortable about entrenching the unconventional and unorthodox policy measures their modern counterparts have taken.

Lords abounds with anecdotes. President Herbert Hoover doctored the monthly labour market reports:

The book’s central message is that the debt burden imposed on Germany at the end of World War I proved to be too much for the country to bear and, eventually, for the world. Now, as then, too much debt might turn out to be the Achilles heel of the world economy with as much, if not greater, disastrous consequences.

The final word has to be Norman’s. In 1948, he wrote:

Maybe, he spoke for Bernanke, Yellen and Draghi, for they may not be as honest as Norman was in admitting to their policy impotence.

The author is an independent financial markets consultant based in Singapore.

This article was published in the July 2016 issue of our magazine. Do try our print edition - only Rs 349 for 3 print issues delivered to your home + 3 months digital access. Subscribe now!

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest