Magazine

The Other Side Of Indira Gandhi: How She Helped Save India’s Wildlife Habitats

- There was much that was wrong with Indira Gandhi. But her invaluable contribution to preserving India’s wildlife and natural habitats cannot be overestimated.

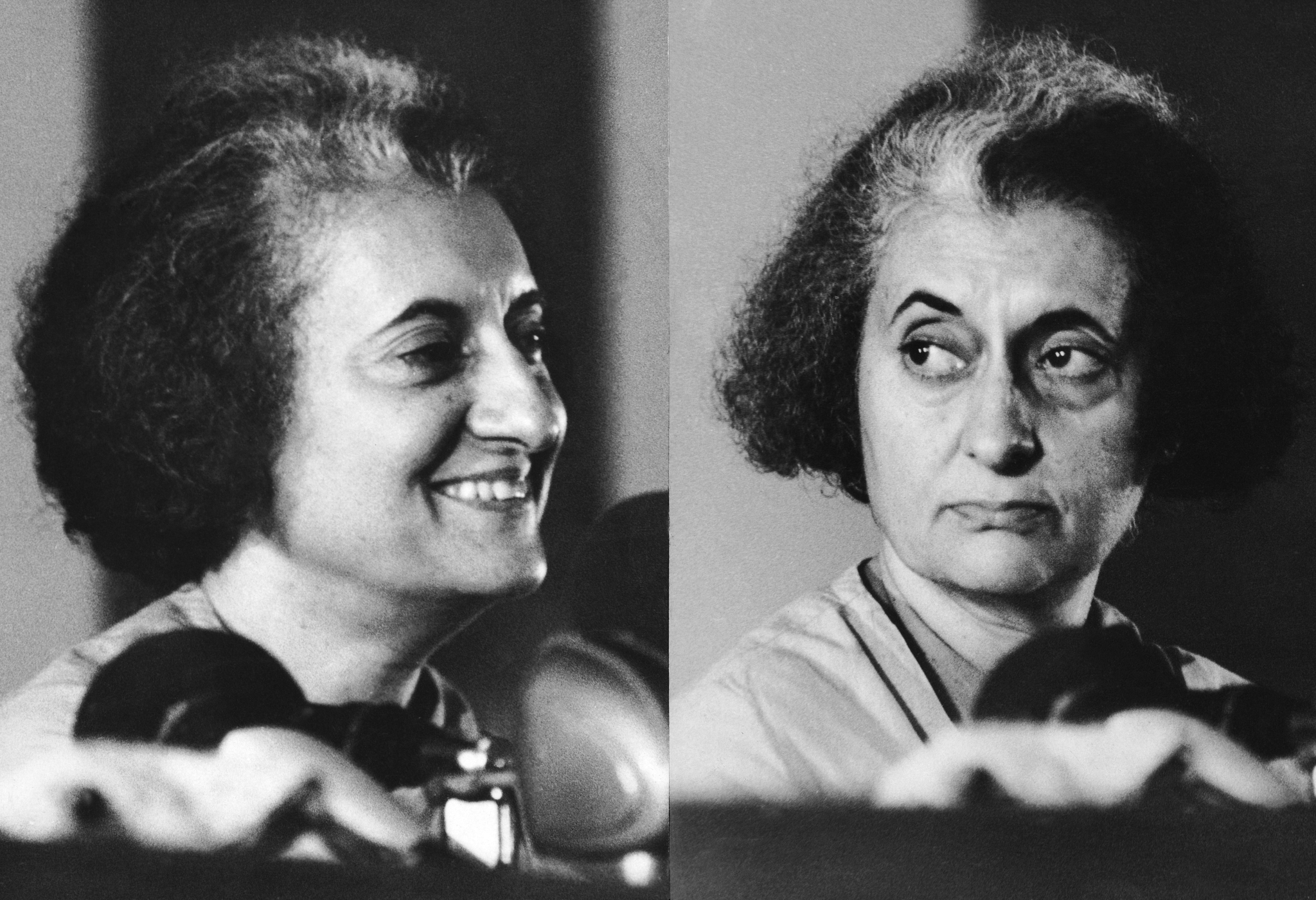

Indira Gandhi (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Indians are generally not very good at biographies. We like to write hagiographies or we like to write lampoons. Rarely does one come across a sympathetic biography which retains balance and which provides fresh insights, not just on the subject of the biography, but on the times that the subject lived in, the events that impacted the subject and the prevailing zeitgeist. We also tend to prefer wide perspectives which result in a lack of fever-pointed focus.

This book is different. It is about a protean personality who is central to the history of India in the 20th century. But by retaining a sharply delineated perspective, it avoids many pitfalls and engages the reader in a supple and substantive manner. This is a book about India, a beautiful but fractured land. It is also a book about a multi-layered complex leader who had her share of encomiums and controversies. As one closes the book, one is swept by a sense of nostalgia, of missed opportunities, but also a sense of fulfillment and an inner conviction that the landscapes of India and the harried denizens who inhabit these landscapes will somehow survive and will continue to give a measure of joy to our descendants.

This book needed to be written. And I for one am glad that it has been written. The structure of the book is very impressive and serves its purpose very well. It is a chronological book. At the beginning of each chapter, there is a brief summary of wider events, especially political events of the concerned period and this summary is printed in charming italics. The rest of each chapter is given over to Indira Gandhi’s intense love affair with the environment, in particular the Indian environment—ecology, birds, rocks, trees, flowers, tigers, turtles, water bodies, mountains—think of it and the subject is covered in enchanting detail.

Hamlet advises the players on their way to Elsinore to “hold a mirror up to nature”. Jairam Ramesh is a good pupil of Hamlet. He simply refuses to show off and intrude into the narrative. Instead, he “holds up” Indira’s letters, diaries, speeches, even her “notings” in the reams of papers and files generated by our bureaucracy, to bring to life a complex personality and her intrepid battle to “save” the land that she clearly loved so much. The book does not try to assess everything about Indira’s politics or her role in Indian and world history. It focuses on just one aspect of Indira—and in doing that it achieves an epiphany rarely seen in works by revisionist historians who seek limelight for the author rather than for the subject.

In February 2008, I wrote a piece in The Indian Express. I quote from there: “Whatever good or bad impartial historians may say about Indira Gandhi’s performance while in power, no one will deny that she had a passionate feeling for the soil and stubble of this land of ours and had a great love affair with the hapless denizens of our forests. She will definitely be remembered as the leader of free India who banned shikar and tried her best to preserve the environment.” Ramesh has written a long, comprehensive, insightful book that simply demonstrates the truth of this assessment of Indira Gandhi. The roots of so-called great political happenings stem usually from the personal. From early in her life, Indira was exposed to the fact that even during long years in prison, her father retained an intense interest and a love for the birds that managed to get past the “stone walls” of the jail. Their shared mystic relationship with the mountains can in part be attributed to their persistent obsession with the land of their ancestors. But it also demonstrates a rather unique relationship that virtually all Indians have with the Himalayas. Shiva of course lives there. Parvati is referred to as “Himagiri-tanaya”—daughter of the Himalayas. Fifteen hundred years ago, Rajasimha Pallava built the Kailasanatha temple in Kanchipuram in the distant south and the Rashtrakutas chiseled out the magnificent Kailasa in Ellora in the distant Deccan, demonstrating that Kailasha, both as a physical object and as a metaphor for the infinite have been deeply embedded in our collective unconscious for a long long time.

In Chapter 10 of the Gita (probably its most resonant chapter), Krishna says: “Sthaavaraanaam Himalaya”—“Among mountains, I am the Himalaya”, again underlining the centrality of the Himalayas in our culture. In his Meghadootam, Kalidasa refers to the Himalayas as the “measuring rod” to be used for the earth itself. Indira did not escape the influence of nature and nurture.

Here are just a few quotations from Indira which Ramesh scatters throughout the book: “Through the ages, India’s thinkers have been inspired by the beauty and majesty of the Himalayas and their sacred associations.” “The Himalayas have shaped our history: they have moulded our philosophy; they have inspired our saints and poets.” “I don’t think the waters of Kashmir can be compared to those of any other country….Ever since I first saw the chinar (sic), I have been lost in admiration. It is a magnificent tree.” “In Kashmir there is always an element of sadness or is it melancholy. Perhaps it is due to willows & their droopy look reminding one of Davies’ poem on the kingfisher: ‘So runs it in thy blood to choose/For haunts the lovely pools & keep/In company with trees that weep.’” “Somehow the sight of such mountains (Everest, Kanchenjunga) gives me a special feeling, I feel aglow from inside.”

As I went back and re-read these quotations in the pages where I had placed bookmarks, it suddenly struck me that Indira Gandhi’s relationship with larger issues associated with the environment is best understood by looking at her references to the Himalayas. While she is intensely aware of ancient and sacred relationships, she also indulges in the immediacy of the experience. The Himalayas inspire not just on account of grand visions, but on account of willows, chinars, kingfishers and the like. She was touched by landscapes, flora and fauna in a very direct way. In June 2008, I wrote another piece in The Indian Express from which I quote: “To love India is to love her hills, valleys, plains, plateaux, estuaries, deltas, marshlands, deserts, rivers, lakes, water bodies, habitations and wildernesses and of course to love the plants, trees, animals and birds that have been with us mythologically and biologically for ever.” And if there is one leader in our history who had this love in tangible, meaningful and effective ways, it was Indira Gandhi.

Some years ago, I met a young man who runs an eco-tourism outfit near one of our national parks. During a late evening conversation, he told me: “The only Indian leader we admire is Indira Gandhi. Without her, there would be no national parks, no wildlife. People working in my field are not bothered about all the other issues for which she gets criticised.”

Many of us keep talking about the excesses of the Emergency or the mishandling of Punjab. But I believe that the young man’s observation is also of great importance. As you read Ramesh’s book, you realise that there is not one sanctuary, one national park, one biosphere in the country which did not benefit from the healing touch of Indira.

Young Indians today flock to these places as part of their indulgence in adventure tourism—hiking, mountaineering, trekking, whitewater rafting, bird-watching and so on. It is important that they should be made aware that all of these experiences would be denied to them but for the decisive, hard-fought battles of Indira Gandhi. You name the place and it crops up in her endless and excruciatingly stubborn correspondence with leaders, bureaucrats, wildlife enthusiasts and unexpected “friends”. Bharatpur, Mudumalai, Gir, Dhulia, Kalakkadu, Dachigam, Kaziranga, Manas, Periyar, Silent Valley, Sariska, Kanha, Chilka, Sultanpur, Corbett, Dudhwa, Tal Chappar, Ranebennur, Velavadar, Bandipur, Palamau, Keibul Lamjao, Diju, Satkosia, Suhelipar, Sunderbans, Kacchh, Pirotan, Porbandar, Bhitarkanika, Namdapha, Pulicat, Nilgiri,Nanda Devi, Wandoor—I have lifted all these resonant names from Ramesh’s book as he quotes from the persevering correspondence of the seemingly tireless Indira.

It wasn’t just sanctuaries and national parks that got her attention. She was concerned about the hills and valleys of India with a passion bordering on the extreme. In her correspondence with dozens of politicians and bureaucrats, she “fought” to preserve the beauty and the natural splendours of Matheran, Mahabaleshwar, Mussoorie, Dehra Dun, Kulu, Manali, and of course Kashmir. And she did not forget urban habitats like the Delhi’s Ridge, Kolkata’s Salt Lake, Chennai’s Guindy, the Adyar estuary and its Snake Park and Mumbai’s Borivali. She was also very concerned about the fragile eco-systems of the North-East, of the Andamans and of Lakshadweep.

And you would think that a powerful leader like Indira would have had it easy. Forget it—this is India. All of us as ordinary citizens are puzzled, intimidated, harassed and stymied by the weird world of India’s bureaucracy. Guess what? Even prime minister Indira Gandhi faced this tripwire all the time. It is not uncommon to find officials and leaders simply not replying to her letters. Like us common folk, she has to follow up! And then of course, there are committees—the bane of modern Indian history. I am sorry, I should have said “committees and commissions”—except that like most bewildered Indians I cannot tell the difference. Indira Gandhi too has to wait endlessly for reports from these august bodies—some never get delivered, some get delivered after years and virtually all of them come up with recommendations which are completely indecisive and which most of the time require the creation of more committees. It is an extraordinary tribute to Indira Gandhi that despite her imperious reputation, she actually put up with these dysfunctional inefficiencies of our much-vaunted federal democracy. It is an even greater tribute to her that she got so much accomplished.

It seems incredible today to think that Indira actually faced opposition when she wanted to ban shikar and the trade in the skins of wild animals. But that was exactly the state of affairs when she became prime minister in the 1960s. As recently as 1971, a certain Shyama Charan Shukla, then chief minister of Madhya Pradesh, was actually upset by what he refers to as “the sudden ban on shooting of tigers”. According to the worthy Mr Shukla, this ban had “considerably disturbed the commitments of shikar outfitters with foreign clients”. He goes on to write that since in the previous year, 29 tigers had been hunted in Madhya Pradesh alone (Dear Reader: Believe me, this is true—the authentic correspondence has been “outed” by Ramesh!), only 29 permits were given in 1971. Luckily for us, due to some bureaucratic mix-up (ah—that glorious Indian phenomenon) only 11 permits were issued (bureaucratically, “issued” is distinct from “given”). And perhaps due to the ineptitude of the hunters, only three tigers were shot. You and I would say that it’s three too many. But in 1971—I’m not talking of 1871, when we can blame the bad British for everything—the fact that Indira had to keep writing letter after letter against the practice of hunting tigers, tells you something about the entrenched mindsets and vested interests that she had to deal with.

Reading the extended correspondence on how to control diplomats who misused their privileged status to indulge in hunting is another horror-comic experience.

Suffice it to say: Indira saved the tiger for us. Of course, she was helped and supported by many. Lord Curzon stands out in our history as the person who forced through the Preservation of Ancient Monuments Act, thus saving at least some of our architectural heritage. Indira’s achievement is probably far more impressive than Curzon’s. Let’s just think of the scale of her achievement. To quote her own words: “Project Tiger is the largest conservation programme adopted for a single species in any country so far.” The naturalist Dillon Ripley pithily captures how the Tiger goes beyond the tiger. “The resounding success of Project Tiger in India has demonstrated in a graphic way how the complete protection of a habitat, ostensibly for a single endangered species, can bring about a total resuscitation and rehabilitation of the entire ecosystem.”

Two of the most important laws that have helped abate and control, if not eliminate the wanton destruction of our fair land—the Law for Protection of Wildlife and the Law for Conservation of Forests were pushed through by Indira Gandhi “almost single-handedly”, as Ramesh points out and pretty much establishes. And while many of us associate her with the tiger, Ramesh does point out that she actually started Project Lion, on behalf of the sovereigns of Gir, a year before Project Tiger took off.

And it was not just these two so-called royal creatures that caught her attention. It is astonishing to see how passionately and diligently and with excruciating attention to detail, she worked to preserve for all of us: hanguls, bustards, Siberian cranes, gharials, flamingoes, Olive Ridley turtles, macaques and even species of the humble deer. How many leaders of the world can say that they actually contributed to preserving in the wild, one of God’s (OK—evolution’s) magnificent creations? Indira can make that claim.

I do realise that this book review is turning out to becoming a bit of a panegyric for Indira Gandhi. Coming from someone usually given to understatement and satire, this represents an extraordinary compliment to the biographer and his subject. Talking about the subject, it is simply remarkable to see how much prescience and perspective Indira Gandhi possessed. She fought relentlessly with the bureaucrats and politicians of states as far apart as Madhya Pradesh and Kerala against the introduction of non-native commercial mono-culture trees. Pretty obvious today. But it required a powerful prime minister’s intervention not that long ago. Let’s take a look at some extracts from her speeches and letters to realise that in more ways than one she anticipated the vocabulary and the phraseology that we take for granted today.

She adds lustre to a dull official file on “land policy” in 1973: “This is not simply an environmental problem but one which is basic to the future of our country. The stark question before us is whether our soil will be productive enough to sustain a population of one billion by the end of the century at higher standards of living than now prevail.” An elementary content analysis would suggest that the sting is in the tail. Our people are entitled to and will have higher standards of living in three decades. The land policy, whatever it be, needs to take that into account. In April 1975, she had this to say in a public message: “…the utilisation of natural resources must go hand in hand with conservation…. The increasing needs of our population are fast encroaching upon forests and pasture areas. Our forests must be preserved because of a variety of benefits as well as their crucial influence on climate.” And to think that university academics were yet to coin the expression “climate change” in 1975! Look at the way she articulates high ideals and practical empiricism at the same time: “India’s rich flora and fauna are under severe threat. The denudation of forests has wideranging harmful consequences. The climate is affected, landslides take place, river beds get silted, hence humans suffer, while many species of wildlife and valuable plants become extinct.”

This gets us to one of Ramesh’s crucial arguments. Indira Gandhi was one of those unusual environmentalists who combined idealism and realism. Ramesh makes the point that she was not a “one-dimensional environmentalist”. She tried hard to strike “a balance between ecology and economic growth”. And what consistently comes through is that she stuck her neck out to take this “middle path” even at the cost of alienating extremists on both sides. It is tough to maintain courage in the face of seductive reductionist arguments and their hysterical supporters. That is why Ramesh is correct when he describes as “churlish” those scholars who have accused her of “top-down environmentalism”.

Anyone who has tried to set up a small institution or run a small business in India knows of the endless stream of obstacles, hurdles, headaches and traumas that this involves. To achieve something so vital and constructive on both a national and on numerous local canvases, in a country where proverbially nothing gets done, is something that needs to be praised and cherished. It does not merit armchair criticism. Incidentally, Indira’s correspondence with so many grassroots workers and leaders like Sunderlal Bahuguna, Veer Bhadra Mishra, Swami Chidananda and others, demonstrates that she was well aware of the importance of bottom-up environmentalism also. She was sensitive not only to responding to popular sentiments but for the need to create an atmosphere where environmental concerns get embedded in our larger national dialogue: “This is not a matter for the government alone. Effective protective and other measures must rest on enlightened public opinion. Every attempt must be made, especially in our schools and colleges, to educate young people about the urgency of conserving the environment.”

Ramesh makes an interesting point that Indira Gandhi had a “deep-seated belief that nature and culture were two sides of the same coin”. Her passionate interventions with insensitive local bureaucracies, pleading with them, imploring them, trying to persuade them to take care of a variety of heritage sites like Jaisalmer, Khajuraho, Mahabalipuram, Konarak, Bhubaneshwar, Fatehpur Sikri, Kushinagar, Sravasti, Brajbhoomi Parikrama Complex, Agra Fort, Delhi’s Red Fort, Hampi, Alchi Monastery in Ladakh, Bharatpur Fort, Elephanta Island—again, a long list of resonant names lifted from the mirror that Ramesh’s book is—confirms Indira’s place along with Curzon on this score. She had the imagination to try to create a National Trust along the lines of the one in the UK. A watered-down INTACH did come into being in 1984, demonstrating that there always seem to be “good” reasons in our country to sidestep best practices. Her efforts with India’s heritage monuments were certainly not marked with the same measure of success which she had with our forests and our wildlife.

One cannot close this review without saying something that needs to be said, despite the controversies that may arise. Indira Gandhi definitely and categorically had an Indic, Hindu view of the environment. It was not an accident that made her give the name Dakshin Gangotri to India’s station in Antarctica. At Stockholm, in her famous speech, she said: “Modern man must re-establish an unbroken link with nature and with life. He must again learn to revoke the energy of growing things and to recognise, as did the ancients in India centuries ago, that one takes from the earth and the atmosphere only so much as one puts back into them.” She then quoted from the Atharva Veda: “What of thee I dig out, let that quickly grow over, let me not hit thy vitals, or thy heart.”

In July 1984, just a few months before her death, she wrote: “For countless centuries, Indian civilisation has proclaimed the oneness of all existence and unity of life and non-life.” This contrasts with the anthropocentric view of many cultures, that the creator meant for man to dominate this planet. Luckily for us, Indira was able to combine this ancient vision with a practical modern scientific perspective and, against substantial odds, translate this vision into practical policies, institutions, projects and actions.

If we have allowed some of her organisational efforts to deteriorate and partially atrophy in recent years, the fault is ours. Again, luckily, perhaps we have time to correct it and preserve our country as one “where the black bucks roam” as is said in the texts of antiquity.

Perhaps, with Indira, we need to forgive (though never forget) her drawbacks and start thinking also of the best portions of her legacy. To this end, Ramesh has made a definitive contribution.

My recommendation: Please buy many copies of this book and give them as gifts to all young people.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest