Magazine

From Bansi Lal To Manohar Lal: A Short History Of Haryana’s Politics

- Uptill very late in his tenure, Manohar Lal Khattar looked out of place in his job.

- Today, as Haryana goes into elections, he looks set to return with a crushing majority.

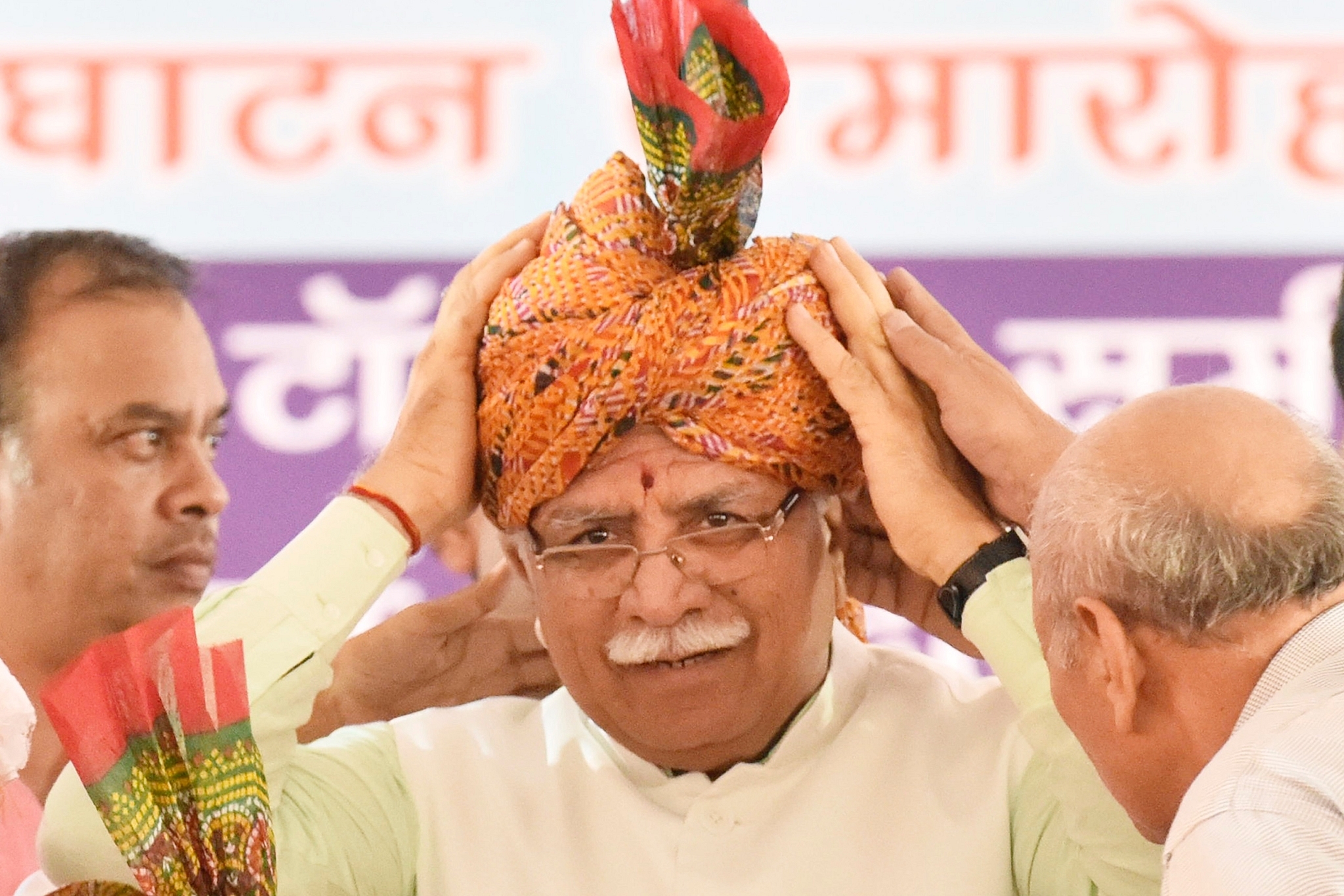

Manohar Lal Khattar, Chief Minister of Haryana.

Haryanvis are, perhaps, one of the most stereotyped people in the country. So is their politics. And without good reason.

The state is much maligned for ushering in the culture of ‘Aya Ram, Gaya Ram’ politics marked by horse-trading, defections and frequent switching of loyalties based on prevalent power equations, where ideology takes a backseat and loyalty to self-preservation trumps everything else.

It also has earned a bad reputation for its corruption culture, nepotism, and dynasty rule. But it would be unfair to single out Haryana and give it a monopoly over these ills of electoral politics, which are found in abundance throughout the country.

Haryana earned the dubious title of ‘Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram’ in its very first election to the state assembly in 1967 thanks to Gaya Lal, an independent legislator from Pataudi who joined Congress, then defected to United Front, then back to Congress and then to Front again — all in a fortnight.

Of course, some of Gaya Lal’s colleagues were even bigger serial defectors than him, but it was he who became immortal thanks to the then Congress leader Rao Birender Singh declaring at a press conference that ‘Gaya Ram was now Aaya Ram’ when the legislator defected to Congress from United Front.

The tradition continues to this day. Most of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) current Members of Parliament (MP) and Members of Legislative Assembly (MLAs) in the state are either veteran leaders who have attached themselves faithfully to the saffron outfit after hopping multiple parties in their career.

Post the BJP’s thumping victory in the Lok Sabha elections, scores of leaders from other parties have crossed over to the BJP, and now the situation is such that the party is spoilt for choice in ticket distribution with at least five to six claimants on each seat.

Haryana is notorious for its dynasties too. It is a land of Lals and lals. There are Lals and then there are their lals (children). Bansi Lal, Devi Lal, Bhajan Lal are three most prominent former chief ministers who have left behind a rich legacy.

After Bansi Lal’s son Surender Singh, a minister in Hooda’s first government, passed away in a chopper crash in 2005, his daughter-in-law Kiran Chaudhary assumed the reins of the dynasty. Her daughter was elected MP from Bhiwani in 2009 but lost badly in 2014 and 2019.

Devi Lal’s son Om Prakash Chautala became chief minister four times — only father-son duo to achieve the feat of climbing the highest political office in the state.

Chautala is currently serving a 10-year jail term in Tihar for corruption along with his younger son Ajay Chautala. Abhay Chautala, his elder son, ran the party in their absence until earlier this year when Dushyant and Digvijay Chautala, sons of Ajay, split the party in half to form their own outfit over differences with their uncle and grandfather, who was pulling the strings from prison.

Now, Ajay and his sons don’t see eye-to-eye with Abhay, his sons and senior Chautala.

Bhajan Lal broke away from the Congress in 2007. He was miffed with the party high command for choosing Hooda over him as chief minister. After he passed away in 2011, his son Kuldeep Bishnoi took charge but with little success.

He merged the party with Congress in 2016. His son, Bhavya Bishnoi, contested from Hisar Lok Sabha unsuccessfully against Chaudhary Birender Singh’s son, another dynast.

Singh, after spending decades in Congress, had jumped ship in 2014 and moved to BJP.

Veteran Congress leader and freedom-fighter Chaudhary Ranbir Singh Hooda couldn’t become chief minister but son Bhupinder Singh Hooda did and how. He served two full consecutive terms (well, almost full — nine-and-a-half years as he had called elections six months early in 2009), the only one to do so in the state’s history.

His son, Deepender Hooda, became MP from Rohtak Lok Sabha three times in a row only to be defeated in 2019 in the second Modi wave. He had escaped the first one. Current Gurgaon MP Rao Inderjit Singh is the son of Rao Birender Singh, Haryana’s second chief minister who was in office for less than a year.

There are multiple tiny dynasties too whose writ doesn’t extend beyond their hometown districts. If I have missed mentioning any significant one, blame it on the state because we have too many to keep a track of.

Apart from being ideology-free and dynasty-ridden, Haryana’s politics can also be accused of being plagued with regionalism. Bhajan Lal’s tenure saw the development of Hisar at the cost of other parts of the state.

Chautalas were accused of looking after their own fief while ignoring those areas which didn’t vote for them. But if someone who has got the maximum flak on this front, it is Hooda.

It’s not because he practised regionalism any more fervently than his predecessors but because he remained in power for 10 straight long years. People weren’t habituated to being ignored for so long.

And on top of all these afflictions, there was blatant corruption at the highest levels in the government, which tormented Haryanvis for decades. If Sonia Gandhi’s son-in-law made the headlines for getting land in the state at throwaway prices this decade, it was Indira Gandhi’s son in the 1970s for the Maruti plant in Gurgaon.

Haryana also became one of the rare states whose former chief minister was successfully convicted for indulging in blatant corruption. While Chautala is still serving his sentence, Hooda has been charge-sheeted by both the Central Bureau of Investigation and Enforcement Directorate.

But despite all these imperfections and defects of the political system, the state has managed to rise as one of the fastest growing in the country. And chief ministers from Bansi Lal to Hooda have played a critical role in helping achieve that.

Bansi Lal, hailed as the modern state’s first vikas purush (development man) electrified all villages way back in the 1970s, launched the much touted highway tourism project, built schools every few kilometres, set up industrial complexes in different areas in his seven-year-long term as chief minister from 1968 to 1975.

Devi Lal didn’t know much about governance but he is considered a pioneer in launching social welfare policies.

Bhajan Lal transformed Hisar into a modern city. Hooda did the same with Rohtak, Jhajjar and Sonipat — areas hitherto ignored by his predecessors. But if there is one thing which he will be remembered for, it is crafting Haryana’s success story in sports.

He also deserves some credit for transforming Gurgaon by inviting modern industries and firms to set up shop in the state. However, his government didn’t care to build infrastructure in the city to match its sprawling growth — one reason why Noida stole the march on Gurgaon.

It has only recently started catching up on infrastructure, thanks to the efforts of Nitin Gadkari and Chief Minister Khattar. Chautala also claims credit for making Millenium City out of a rocky village.

But as with other major cities which sprung up post 1991 economic reforms, Gurgaon’s success is also largely due to private enterprise as well as its proximity to the national capital.

Haryana was also the benefactor of Green Revolution and reaped rich dividends. The leaders of the state as well as people have also had the good judgement of always siding with the party in power at the Centre, ensuring a same-coalition government in Chandigarh and Delhi, translating into “good running of double engine” as Prime Minister Narendra Modi likes to put it.

In this backdrop, the BJP came to power in 2014 for the first time in the state riding on the coattails of Prime Minister Modi as well as due to anti-incumbency sentiment against a decade-long old government which had earned notoriety for being corrupt and focusing on only select pockets for development.

After a gap of 18 long years, a non-Jat became chief minister when BJP selected Manohar Lal Khattar — the fourth Lal — to head the government.

He faced fierce opposition from outside the government and a muted resistance from within his party’s state unit.

Barring a few in Sangh circles, he wasn’t well known even in the BJP let alone among the masses who hadn’t heard of him before the election. Everyone was betting against him and wishing for him to stumble, fail and fall.

He did fail. Repeatedly. At least that’s how everyone saw it. Soon after assuming charge, he came under fire for how his government handled violent followers of Rampal who had defied court orders of arrest and was hiding in his ashram in Hisar.

In early 2016, the Jat reservation movement which turned violent and claimed more than 30 lives, almost did him in.

Chief Minister Khattar had barely recovered from that, when the mayhem unleashed by followers of Dera Sacha Sauda in Panchkula in early 2018 again seemed to prove his detractors right. They again bayed for his blood. But the party bosses in Delhi kept their faith in Khattar.

Until last year, Khattar didn’t seem to be in control. The only thing that was going in his favour was his clean image. He had put an end to all kinds of corruption, which Haryana was infamous for. But it wasn’t enough. In fact, it was proving counter-productive especially among the party cadre.

Given the lack of ideological or party loyalty, leaders and people flock to a party in the hope they will get personal favours when in power.

But Chief Minister Khattar was in no mood to dole out government jobs to the party faithful or even entertain requests from ministers or his MLAs for transfers or contracts for their loyalists.

But soon Khattar’s fortunes took a turn for the better. In December 2018, BJP swept mayoral polls in five big municipalities of Rohtak, Hisar, Karnal, Panipat and Yamunanagar.

It was truly an inflection point. Those who were sure that Chief Minister Khattar will be a one-term wonder, started realising the gravity of one past incident.

It dawned on them how gravely the violence during Jat quota agitation has polarised the state even in areas where Jats had minimal presence.

One month later, it won the Jind by-poll with a huge margin in Jat heartland. It fielded a non-Jat against Jat candidates ran by Chautalas and Congress.

The demographics did the rest. But it wasn’t just that. Yes, polarisation was the biggest factor but there was more, something which analysts had also overlooked.

Khattar’s war on corruption may have been resented by his own partymen the most but it was starting to bear fruit on the ground. Just before the Jind election, the state government announced results for 18,000 Group-D jobs and Jind came third with over 1,600 applicants qualifying.

In fact, the areas which bagged the most number of jobs were not BJP strongholds. The party had lost there in 2014. This proved to the people that the jobs were being given in a transparent manner.

In his five-year tenure, Khattar government has given more sarkari jobs than what the state governments of Hooda and Chautalas did in the last 15 years before 2014.

How could no one — from the shrewdest seasoned politicians to wily political operatives who stayed in power for years — crack this easy puzzle: that this could work wonders in a state crazy for sarkari jobs? It took a novice like Khattar to understand its importance.

Because these vacancies are filled in a totally transparent manner, people from lower and poor sections of the society have benefitted the most. With bribe culture gone and merit the criterion, students have started focusing on studying rather than worrying about arranging money for cooling palms of corrupt middlemen or running behind politicians wasting time.

Coaching classes are coming up everywhere. The amount of goodwill Khattar has earned among masses with just one move, especially among the youth, has only one parallel that I can think of: when Devi Lal had started monthly pension for the old-age folks in 1977.

Khattar has also ended the culture of regionalism — favouring one’s hometown district or those areas which vote for you — over others. When people see public works being done in constituencies which didn’t vote for the BJP in 2014, it strikes them as something of an alien concept.

Now, there is no waiting for someone from your area to become chief minister to see vikas.

While the ‘Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram’ culture is alive and kicking, Chief Minister Khattar has introduced a new governance model to Haryanvis: free of corruption and graft, which works for all parts of the state’s citizens based on their needs and not on their political affiliations. It is due to this culture that those politicians, especially dynasties, which thrived on regionalism or personal loyalties, have been dealt a body blow.

No wonder that Khattar is all set to return for a second term and this time with an even much bigger majority. The opposition is merely fighting for relevance, not to win.

Of course, the BJP has been able to achieve it all by polarising the state along Jat-non-Jat lines, however strongly it may deny that fact. This has been the price that the state has paid for Chief Minister Khattar’s good governance.

He has cleaned up a lot of mess but Haryana has got infected with this deadly virus like never before. One hopes that in the next five years, the state gets itself rid of this poison of caste tensions and rises to new highs.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest