Magazine

Wily Jinnah’s Flip Flops, Before And After The Partition

- In the days leading up to and immediately following Partition and Pakistan’s birth, Jinnah kept flip-flopping in his public statements, as it suited him.

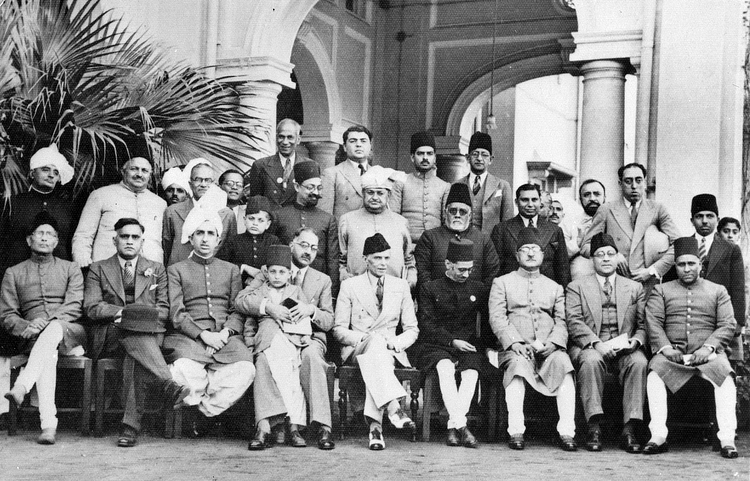

Muslim League leaders after a dinner party given at the residence of Mian Bashir Ahmad, Lahore, 1940. Group portrait with Jinnah seated in the centre. (British Library)

As Muslim refugees from East Punjab streamed into Pakistan following the Partition massacres, Mohammad Ali Jinnah initially reiterated his oft repeated belief in exchanges of population, something he had first articulated soon after the All India Muslim League’s (AIML) Lahore Resolution in 1940 and would repeat, following the Bihar and Garhmuktesar riots in 1946. As he noted, “if the ultimate solution to the minority problem is to be mass exchange of population, let it be taken up on a governmental plane and not left to be sorted out by bloodthirsty elements”.

But as Pakistan faced a flood of refugees, Ghazanfar Ali Khan, the Pakistan Rehabilitation Minister, made it clear that it did not want any exchange of population. Prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan’s statement that the government of Pakistan was absolutely opposed to migration of Muslims from Delhi, the western parts of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh (now Uttar Pradesh – UP) and areas outside East Punjab came as a major psychological blow to UP Muslims.

Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman’s exit to Pakistan after having joined the Constituent Assembly as the leader of the opposition and pledging his loyalty to the Indian Union, was the last straw on the camel’s back. Two chartered planes flew the family and its possessions to Pakistan. Incensed Congress members in the UP Assembly asked Muslim League (ML) MLAs to resign, forfeit their citizenship and move to Pakistan. Congress MLA Charan Singh declared that the “inexorable logic of Partition of Mother India on a religious basis can admit only of two peaceful solutions of the problem, namely an exchange of population or an unqualified denunciation of the two-nation theory by the Muslim Leaguers and the launching of an active enthusiastic campaign by them for the unification of the two dominions. There is no other middle path. Not all the efforts of our Nehrus and (Govind Ballabh) Pants can bring peace to this unfortunate land otherwise.”

The UP Congress president on the other hand added that the Congress could not be fooled by the professions of loyalty to India so freely and frequently made by Muslim Leaguers nowadays. Their sole aim seemed to be to enter the Congress by backdoor methods and get a share in the administration. “I want to tell the Leaguers your infiltration tactics and sabotaging would not succeed. We know you have always betrayed the country, you stabbed us in the back and so we will give you your proper place.”

The ML also faced Dr B R Ambedkar’s wrath since the Pakistani government was barring Scheduled Castes from migrating to India as it cited the maintenance of essential services in Pakistan as the reason. He condemned Pakistan and Hyderabad for violence against Scheduled Castes and attempts to forcibly convert them to Islam. Sri Prakasa, the UP Congressman who was sent to Pakistan as India’s first High Commissioner, notes that when he asked Liaquat Ali Khan why these people were being barred from going to India for a month to see their families, Liaquat responded, “Who would clean the streets and latrines of Karachi if they did not come back?” Significantly, Ambedkar added that “the union of Hyderabad with India must be insisted upon because the geographical unity of India is indestructible and no state can be allowed to violate it”.

The AIML met for one final time in Karachi towards the middle of December 1947. It led to some fireworks. Jamal Mian launched a frontal attack on the Pakistan government and objected to the use of the term “Muslim state” in the official resolution of the council of the ML. The young man reportedly burst out, “For God’s sake do not call yourself a Muslim state and thereby blemish the fair name of Islam. You have exploited Islam enough. I beg you to call a halt now. The ways of your government and the behaviour of your governors and ministers are not those of Muslim states. If you persist in calling yourself a Muslim state, we would expect the same standard of behaviour from you as those of our pious Caliphs. You know, you cannot lead the life of those pious men when bribery and corruption reigns supreme under your aegis.”

He also launched a frontal attack on Jinnah. “We put you on the highest pedestal. We acknowledged no other leadership. We put complete faith in you to guide our destiny. When you unceremoniously bid us farewell, leaving us in the lurch, our ship became rudderless and destruction stares us in the face. We are not afraid of our annihilation provided we are assured that Pakistan which you have built by sacrificing us will be worth living for those who are there. Unfortunately, what we see now gives us no such hope.”

He was lustily cheered when he attacked the ministry and the behaviour of its members. Jinnah had earlier swatted away such arguments by deploring the “insidious propaganda” that “minority provinces” Muslims had “been let down by the ML, and that Pakistan is indifferent to what may happen to them”. He bluntly stated that “they were fully alive to the consequences they would have to face remaining in Hindustan as minorities but not at the cost of their self-respect and honour. Nobody visualised that a powerful section in India was bent upon ruthless extermination of Muslims and had prepared a well-organised plan to achieve that end. This gangsterism, I hope, will be put down by the Indian government.” The next day, Jamal Mian dropped his amendment for the deletion of the term “Muslim state”.

Muslims were by now largely seen as fifth columnists and their loyalty to the Indian Union was demanded through public obeisance to the symbols of the new nation. Leader reported that three assistant masters of Government Jubilee High School in Gorakhpur – Abdur Rahman, Abdur Rahim, and Shabbir Hasan – had been pulled up by the authorities for their failure to salute the national flag on 15 August. Explanations were demanded for their behaviour, and when given, deemed inadequate. The report noted that they were going to be given another opportunity to clear their names by saluting the flag in front of staff and students.

In contrast to their position in UP, the mohajirs (the Urdu-speaking people who migrated to Pakistan) went on to wield considerable influence in Pakistan in its early days, shaping the idea of Pakistan in ways that would have a lasting impact on its identity. We may begin this side of the story with the Qaid-i-Azam, who, though not a mohajir from UP, was certainly a migrant from Bombay. A few days before Viceroy Lord Mountbatten’s momentous 3 June declaration, Jinnah confidently remarked to an American diplomat taking leave of him: “I tell you we are going to have Pakistan – there is no question about it. Delhi will soon be of no importance whatsoever.”

But as Independence approached, the Qaid, mindful of the incredibly tense communal situation following the horrific massacres of Muslims in Bihar and Garhmuktesar and the apprehensions felt by Muslims in Hindustan made a soothing remark. He grandly declared, “I am going to Pakistan as a citizen of Hindustan. I am going because people of Pakistan have given me the opportunity to serve them. But this does not mean I cease to be a citizen of Hindustan. Just as Lord Mountbatten who is a foreign citizen has accepted the Governor Generalship of Hindustan in response to the wishes of its people, similarly I have accepted the Governor Generalship of Pakistan. But I shall always be ready to serve the Muslims in Hindustan.” The same sentiment, more than his touted secularism, would motivate Jinnah’s 11 August speech a few days later. But this statement itself was in sharp contrast to earlier remarks wherein Jinnah flatly noted that “I do not regard myself as an Indian”. Before leaving for Karachi, the Qaid sold his Delhi residence on Aurangzeb Road to his old friend Seth Ramkrishna Dalmia who promptly converted it into the headquarters of the Cow Protection League and asked 10 August to be celebrated as Cow Day in the country. Jinnah had tried to sell his Malabar Hill residence in Bombay in 1944 to the Nizam of Hyderabad but the deal never materialised and the property was ultimately sealed by the Government of India. On the other hand, Liaquat Ali Khan’s property was leased to the government of India by Begum Raana Liaquat for two years and hence was not requisitioned.

In any case, Jinnah’s bold optimism about a “moth-eaten, truncated Pakistan” that he had rejected a few years earlier, echoed the sustained confidence and public enthusiasm that both ML elites and cadres displayed in the run-up to Partition. Fiercely protective of Pakistan’s sovereignty, Jinnah made it clear that Pakistan would never agree to a constitutional union with India. American journalist and photographer Margaret Bourke-White, who met Jinnah at his Viceregal residence soon after, described his demeanour in terms of “a fever of ecstasy”. As she wrote, his “deep sunken eyes were points of excitement” and “his whole manner indicated that an almost overwhelming exaltation was racing through his veins”. Jinnah reminded her that Pakistan was “not just the largest Islamic nation but the fifth largest nation in the world”. This dual emphasis on Pakistan as the leader of the Islamic world and a major modern state in the world of nations, a new Medina as it were, standing on the vista of breathtaking possibilities, reflected a widespread sense of excitement about the prospects of this new nation state. But balancing these twin imperatives in a creative roadmap that would enable Pakistan to realise its potentialities posed a formidable challenge to the new nation state.

Jinnah himself struggled to find the right balance or give content to this new project as he shepherded Pakistan’s early destiny. When Bourke-White pressed Jinnah to reveal his plans for Pakistan’s constitution, the constitutional lawyer most suited to “correlate the true Islamic principles with the new nation’s laws” stuck to generalities, remarking, “Of course it will be a democratic constitution; Islam is a democratic religion… Democracy is not just a new thing we are learning. It is in our blood. We have always had our system of zakat – our obligation to the poor… Our Islamic ideas have been based on democracy and social justice since the 13th century.” Jinnah’s famous 11 August 1947 speech, praise for which would land L K Advani in hot water 60 years later, was perhaps an attempt at restoring some balance, but it only created much confusion and consternation in Pakistan.

Jinnah however soon reverted to his artful ambiguity on the matter. In a speech to the Sindh Bar Association in Karachi on 25 January 1948, he even seemed ready to abandon his earlier stance, which had called for religion to be kept out of politics, denouncing as mischief, “attempts to ignore Shariat Law as the basis of Pakistan’s constitution”.

His ambivalence on the matter can further be gauged from his refusal to throw the ML’s doors open to all of Pakistan’s religious communities, stating that “time had not yet come for a national organisation of that kind”. Jinnah’s own colleagues, especially from the UP, were far from ambivalent on the matter. As Sri Prakasa noted, Jinnah was taken to public meetings large and small by “friends he had known in India who would ask the audience, ‘Do you want to be ruled by the Indian Penal Code or the Quran?’ And they would reply, ‘Quran.’”

Along with Islamic democracy, Jinnah called for the inauguration of an Islamic model of economic development, arguing that Pakistan needed to work out its destiny in its “own way and present to the world an economic system based on the true Islamic concept of equality of manhood and social justice”. This model of Islamic development or social justice was at times presented in terms of Islamic socialism but the state in Pakistan was far from approximating this ideal, in part due to Jinnah’s own conservative instincts and in part due to the class composition of the ruling elites.

The charge d’affaires in the American embassy in Karachi noted with astonishment that salaries of provincial governors in Pakistan ranked “far above the salaries provided for almost all the governors in the United States”. He found this ironical “in view of the great lack of capital in Pakistan, the poverty of the overwhelming majority of the people, and the fact that the new government will probably apply to the US for financial assistance in the near future”. It was “more startling” since one of the main criticisms directed against British rule in India was the exorbitant salaries paid to governors and other officials at the expense of the masses.

Excerpted From Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India (Cambridge University Press, 2015), which was cited as the Best book in Global Non-Fiction in 2015 by Newsweek magazine.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest