Magazine

Women Of Substance

- The Pancha Kanyas (Five Virgins) of our epics embody the defiance of patriarchal notions of sexual morality. And none of them were “virgins” in the usual sense; indeed, all had sex with more than one man. Their stories have never been as significant as they are today.

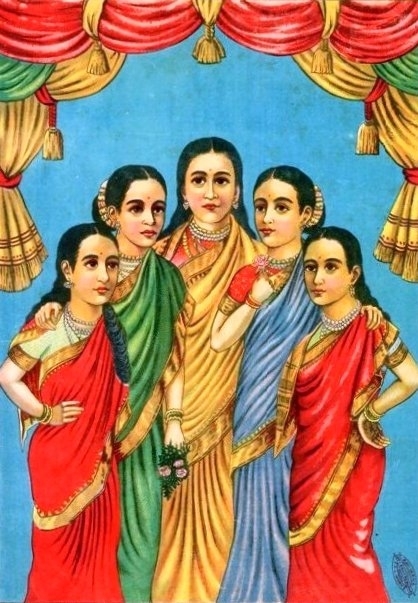

Panchakanya/Photo credits: Wikipedia

There is a traditional Sanskrit exhortation that goes: Ahalya Draupadi Kunti Tara Mandodari tatha panchakanya svaranityam mahapataka nashaka “Remembering ever the virgins five—Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Tara and Mandodari/Destroys the greatest sins.”

Two things about this verse stand out: the use of the epithet kanya (virgin, maiden), not nari (woman); and the unusual combination of names that redeem the sinner.

There is another traditional verse celebrating five satis or chaste wives: Sati, Sita, Savitri, Damayanti and Arundhati. Are then Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Tara and Mandodari not chaste wives because each has “known” a man, or more than one, other than her husband? If so, why should invoking them be extolled as redemptive? Moreover, why is the intriguing term kanya applied to them?

Of this group, Ahalya, Tara, Mandodari belong to the Ramayana, while Draupadi and Kunti are celebrated in the Mahabharata, Harivamsa and the Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata and Bhagavata Puranas.

The first point to keep in mind is that Valmiki and Vyasa’s great compositions are designated as kavya, or truth perceived by a kavi (seer-poet). Hence, in evaluating the characters they have created, it is necessary to probe beneath the surface reality to reach the eternal truths on which these are founded.

When an exhortation such as this has been handed down over a millennium, it cannot be dismissed as a meaningless conundrum. Given the fact that western-style feminism holds sway in modern India, it is important to comprehend what this intriguing verse seeks to convey.

AHALYA

The name Ahalya itself has a double meaning: one who is flawless; also, one who has not been ploughed, that is, a virgin. According to the Uttarakanda Ramayana, Brahma, after having created her from what was unique and loveliest in all creatures, entrusted her to the care of the sage Gautama and later, presumably when she had reached maturity, gifted Ahalya to him as his spouse. Indra, however, resented this; he had presumed that this exquisite woman was meant for him.

In the Adikanda, Vishvamitra states that when Indra, assuming Gautama’s form in his absence, approached Ahalya, she knew it was Indra in disguise, but, out of curiosity, consented to grant him sexual favours. Thereafter, she told Indra, “I am gratified. Now leave this place quickly, best of gods! Protect yourself and me from Gautama in every way.” But Gautama returned as Indra was departing and because of his curse, Indra’s testicles fell off. Ahalya was condemned to perform penance in that terrible forest, hidden from all, fasting, subsisting on air, sleeping in ashes, tormented by guilt. Gautama ordained that she would be purified of delusion and greed by offering hospitality to Rama and then would be able to rejoin him.

The Adikanda account is frank about Ahalya’s conscious choice to satisfy her curiosity. The sole beautiful woman in creation, she is the eternal feminine responding characteristically to the ardent, urgent, direct sexual advances of the ruler of heaven who presents such a dazzling contrast to her ascetic, aged, forest-dwelling husband. Although Ahalya has already had a son, Shatananda, by Gautama, her womanhood remains unfulfilled. The kanya is not just mother but also beloved, and this aspect has not been actualized in her relationship with Gautama. As the first kanya not born of woman, she has the courage to go with her inner urge. The Uttarakanda version is exculpatory, as is only to be expected in a later addition to the epic. In this version, Agastya says that infuriated at Brahma gifting Ahalya to Gautama, Indra raped her. Though Ahalya protests that she could not recognize the disguised Indra and is not guilty of wilful wickedness, Gautama says that he will take her back only after Rama has purified her.

We witness here a male backlash that condemns the woman as soiled even though she may not be at fault.

In the Kathasaritsagara version, Indra flees in the form of a cat but is still cursed. On Gautama’s asking who has been in the cottage, Ahalya answers that it was a majjara (Prakrit for “cat” or “my lover”). She is then punished by being turned to stone.

This is actually not a physical transformation, but symbolises social ostracism and the consequential psychological trauma, in which the oppressive guilt throttles the vital spirit. Ahalya becomes a living automaton, denying her emotions, feelings and self-respect, and is shunned by all. Even as mother, she finds no fulfilment; Shatananda abandons her in the forest despite referring to her as renowned.

Rama regards her as blameless and inviolate. When he and Lakshmana touch her feet in salutation, this recognition restores her self-respect and her status in society, so that she truly lives again. Vishvamitra repeatedly refers to her as mahabhaga, most virtuous and noble. For him, Ahalya was not a fallen woman. She had been true to her independent nature, fulfilling her womanhood in a way that she found appropriate, although unable to assert herself finally.

In this unique type of sexual encounter with non-husbands, that is neither rape nor adultery, lies the key to the mystery of the five “virgin” maidens.

TARA

Tara, wife of Bali, is a woman of unusual intelligence, foresight and self-confidence. When her brother-in-law Sugriva comes to challenge Bali after being defeated once, she warns her husband against responding, pointing out that appearances are deceptive, for normally no contestant returns to the field so soon after being soundly thrashed. Moreover, she has heard that Rama has befriended him. By brushing aside her wise warning, Bali gets killed by Rama’s arrow. To ensure that her son, Angada, is not deprived of his father’s throne, Tara becomes Sugriva’s consort.

When Lakshmana, furious at Sugriva not providing the promised help for rescuing Sita, storms into the city of Kishkindha, it is Tara whom the terrified Sugriva sends to tackle him. Approaching Lakshmana with intoxicated eyes and unsteady gait, the seductive Tara effectively disarms him. She gently reprimands Lakshmana for being unaware of lust’s overwhelming power which overthrows the most ascetic of sages, whereas Sugriva is a mere vanara. When Lakshmana abuses Sugriva, Tara fearlessly intervenes, pointing out that the rebuke is unjustified and details all the efforts already made to gather an army. Once again, as when tendering advice to Bali, Tara shows her superb ability to marshal information. Thus, she acts as Sugriva’s shield while ensuring that her son Angada is made the crown prince.

MANDODARI

Valmiki has hardly written anything special about Mandodari except that she warns Ravana to return Sita and has enough influence to prevent his raping her. Further, like Tara, she accepts her husband’s enemy and brother, Vibhishana, as spouse, either at Rama’s behest, or because it was the custom among the non-Aryans for the new ruler to wed the enthroned queen. But in the Adbhut Ramayana, we find Mandodari violating Ravana’s injunction not to drink from a pot in which he has stored blood gathered from ascetics. By doing what she felt moved to do, Mandodari shows she is not her husband’s shadow.

The consequence is that she becomes pregnant, and discards the newborn female infant in a far-off place. Which happens to be the field Janaka ploughs to discover the orphan Sita.

Tara and Mandodari are parallels. Both offer sound advice to their husbands who recklessly reject it and suffer. Then both deliberately accept as their spouse the younger brother-in-law responsible for the deaths of their husbands. Thereby, they are able to keep the kingdom strong and prosperous as allies of Ayodhya and continue to have a say in governance. Neither can be described as shadows of such strong personalities as Bali and Ravana.

KUNTI

In the Mahabharata, Shura of the Vrishnis gifts his daughter Pritha, when just a child, to his childless friend Kuntibhoja (she is then renamed Kunti). She grows up motherless in Kuntibhoja’s home and is handed over, in teenage, to the eccentric, irascible sage Durvasa. Her foster father warns that should she displease the sage, it will dishonour his clan as well as her own. We know that she is strikingly lovely, for Kuntibhoja exhorts her not to neglect any service out of pride in her beauty. She heeds his words and Durvasa grants her the boon of being able to summon any god by chanting a mantra.

Kunti, like Ahalya, is curious. She wishes to test whether Durvasa’s boon really works. Perceiving a radiant being in the rising sun, she invites him, using the mantra. Surya will not return unsatisfied. He cajoles and browbeats the nubile maiden, assuring her of unimpaired virginity and threatens to consume the kingdom if denied. Mingled desire and fear overpower Kunti’s reluctance and she stipulates that the son thus born—Karna—must be like his father.

Kunti is a remarkable study in womanhood. She chooses the handsome Pandu in a swayamvara only to find Bhishma snatching away her happiness by marrying him off immediately to Madri. She insists on accompanying her impotent husband into exile and faces an incredibly horrific situation: her beloved husband insists that she get son after son by others. It is in this husband-wife encounter that Kunti’s individuality shines forth.

At first, she firmly refuses, saying, “Not even in thought will I be embraced by another.” Although this is somewhat ironic as she has already embraced Surya and regained virgin status after delivering Karna, it is evidence of her resolve to maintain an unsullied reputation. Nothing must interfere with the chances of a restoration to the throne.

That is why she does not tell Pandu about Karna even when he enumerates various categories of sons, including one born to the wife before marriage. Children born with the sanction of her husband would be a completely different proposition from one born to her as an unmarried princess. Pandu urges that she will only be doing what is sanctioned by the northern Kurus, that the custom of being faithful to one’s husband is very recent, and cites the precedents of his own mother and stepmother, Ambalika and Ambika, and even quotes a scriptural directive for implicitly obeying the husband’s commands: “The woman who,/ Commanded by her husband to procreate children, refuses,/ Is guilty of the sin of infanticide.”

This has no impact on Kunti, who is far stronger than her husband. She gives in only when Pandu abjectly begs her, and, with delightful one-upwomanship, only then reveals her boon.

Vyasa’s account of Kunti’s encounter with Dharma, the first god she summons after marriage, is wonderfully succinct: “He smiled./’Kunti, what can I give you?’/She smiled,/ ‘A son.’” There is no coy coquetry here, no bashfulness. A need is voiced to someone who is known, and is fulfilled.

When Kunti summons Vayu, she is described as smiling shyly, for he is a stranger. Kunti will not be dictated to by Pandu in choosing the person who will impregnate her. Her smile indicates precisely her assertion of freedom of choice, selecting the father of her son four times over.

Later, when Pandu urges her to give him more sons, she bluntly refuses, quoting the scriptures to him, just as he had: “The wise do not sanction/A fourth conception, even in crisis./ The woman who has intercourse/ With four men has loose morals;/ The woman who has intercourse/ With five is a prostitute.” (Remember here that Kunti has not revealed to Pandu that she slept with Surya, so Pandu believes that she has had sex with only three men)

Along with sagacity, she shows remarkable control over herself. She will not going to go on indiscriminately satisfying her sexual or maternal urges.

Kunti’s maturity and foresight, and use of the learning from experiences to arrive at swift decisions that benefit both society and her children, set her apart and above all characters in the Mahabharata, except perhaps Krishna. She brings up five children in a hostile court, bereft of relatives and allies. It is she who alerts Yudhishthira to the secret message in Vidura’s parting words when they are going off to Varnavata. It is she who gets the Nishada woman and her five sons drunk in the house of lac so that no evidence is left of the Pandavas’ escape from the gutted dwelling.

Kunti’s decision to proceed to Panchala—the traditional enemy of Hastinapura—is also well thought out. It is aimed at winning Draupadi, the daughter of King Drupada, to forge a princely alliance with the kingdom and challenge the Kauravas.

Draupadi becoming the common wife of the five brothers was also the result of Kunti’s foresight. Earlier, Vyasa had already briefed her about Draupadi being fated to have five husbands because of the boon Shiva had given her in a previous birth.

Kunti knows that the only way to forge an unbreakable link among the five is not to allow them to get engrossed in different wives. Any split will only frustrate the goal of getting control of Hastinapura.

Till now, their lives have been governed by her and have revolved only around her. She can be replaced only by a single woman, not five, if that unified focus is to persist.

Hence, Kunti deliberately asks that whatever has been brought should be shared and enjoyed as usual. After “discovering” her “mistake”, her only worry is that something must be done so that her strategy does not fail. Yudhishthira’s speech to Drupada amply clarifies that the decision is Kunti’s, though the brothers have eagerly acquiesced, each having Draupadi in his heart.

It is also a magnificent tribute to the total respect and implicit obedience of the brothers to Kunti. Despite all the paeans to Gandhari’s virtues, her complete failure as a mother to command any respect from Duryodhana only serves to highlight the qualities which make Kunti pre-eminent among all women in the Mahabharata.

In Panchala, Kunti chooses to stay in the hut of a potter. She brings up her sons from virtually the lowest rung of society to become rulers of the kingdom. In that process, she turns necessity to glorious gain. The enforced exile brings her sons into intimate contact with the common people, so that it equips them as true rajas, those who discharge the duty of pleasing their subjects.

Hereafter, Kunti retreats into the background, giving up pride of place to Draupadi. Proof of her astonishing self-effacement is seen in the Pandavas not consulting her when invited to the dice game, which is very unusual, given her overarching influence over them till the marriage. This first instance of her removing herself from the decision-making role leads to disaster.

After this, she emerges from the shadows to intervene decisively thrice. When her sons are exiled, she decides to stay back in Hastinapura as a silent but constant reproach to Dhritarashtra about her sons’ violated rights. Later, in the Udyoga Parva, she tells Krishna, who has come on a peace mission, to urge Yudhishthira to fight for their rights as Kshatriyas must.

To secure the safety of her sons, she takes the conscious decision to undergo the trauma of acknowledging her shame to her first-born, kept secret so long. Though Karna rejects her request, in that apparent failure lies Kunti’s victory. For, she obtains his promise not to kill any Pandava but Arjuna. Moreover, she effectively weakens him from within. While he knows that he is battling his mother’s sons, they are only aware that he is the detestable charioteer’s son who must be slain for his crimes against Draupadi and—later—Abhimanyu.

Kunti has that rare capacity to surprise us which distinguishes the kanya. When all that she had worked for has been achieved, she astonishes everyone by retiring to the forest with, of all persons, Dhritarashtra and Gandhari, to spend her last days serving those who were responsible for her sufferings. Kunti’s reply to her sons’ anguished questions is that she had inspired them to fight so that they did not suffer oppression, and that having glutted herself with joy during her husband’s rule, she has no wish to enjoy a kingdom won by her sons.

How effortlessly she transcends the symbiotic bonds of maternity! Seated calmly, she accepts death as a forest fire engulfs her. It is profoundly significant that the epic declares her to be the incarnation of siddhi, fulfilment.

She is indeed the consummation of womanhood and the archetype of the modern phenomenon which is of such concern all over the world today: the Single Mother.

Making her own way in a hostile world, she establishes her sons and ultimately sublimates the ego. Finally, she transcends the self to give up her life, reconciled, made whole, calm of mind, all passion spent.

Kunti is a “virgin” in the Jungian sense. Originally, this word connoted precisely the opposite of what it has come to mean. Ishtar and Aphrodite, the goddesses of love in ancient Mesopotamia and Greece, were called virgins. The later patriarchal cultures denounced them as immoral and wanton. The boon of virginity is not just a physical condition but refers to an inner state of the psyche which remains untrammelled by any slavish dependence on another, on a particular man.

DRAUPADI

Like Ahalya and Sita, Draupadi is ayonija, not born of woman. She is invoked by a sacrificial rite to wreak vengeance. Like her mother-in-law Kunti, she “knows” more than one man. Yet, hers is an immeasurably greater predicament. Where Kunti’s encounters were momentary, Draupadi has to live out her entire life parcelled out among five men within the sacrament of marriage. But like Kunti, she remains a virgin, regaining that status after each marriage. According to Villipputhur’s Tamil version of the epic, Draupadi bathes in fire after each marriage, emerging chaste like the pole star.

A true “virgin”, Draupadi has a mind of her very own. At the swayamvara, it is her categorical refusal—wholly unexpected—to accept Karna as a suitor that alters the entire complexion of that assembly and, indeed, the course of the epic itself.

Panchali is fully conscious of her beauty and its power, for she uses it in getting her way with Bhima to kill Kichaka when the Pandavas are living incognito, and with Krishna in turning his peace mission into a declaration of war.

The manner in which Draupadi manipulates Bhima to destroy Kichaka is a fascinating lesson in the art and craft of sexual power. She does not turn to Arjuna, knowing him to be a true disciple of Yudhishthira as seen during the dice game. Bhima alone had then roared his outrage. Now she seeks him out at night, snuggling up to the sleeping Bhima. As Bhima awakens, Draupadi addresses him in dulcet veena-like tones. To rouse his anger, she narrates all her misfortunes, even how she, a princess, has now to carry water for the queen’s toilet and particularly mentions how she swoons when he wrestles with wild beasts.

Finally, in an ineffable feminine touch, she extends her palms to him, chapped with grinding unguents for the queen. His reaction is all that she had planned for so consummately. Kichaka’s fate is sealed.

When the lustful Kichaka has been pounded to death by Bhima, she recklessly flaunts the corpse before his kin, revelling in her revenge. They abduct her and she is again saved by Bhima from being burnt to death.

Earlier, during the dice game, Draupadi shocks everyone by challenging the Kuru elders’ concept of dharma in the midst of a crisis where the modern woman would break down. She succeeds in winning back freedom for her enslaved husbands. Karna pays her a remarkable tribute, saying that none of the world’s renowned beautiful women have accomplished such a feat: like a boat, she has rescued her husbands who were drowning in a sea of sorrows. When Dhritarashtra offers her three boons, she takes two and with striking dignity, refuses to take the third, because with her husbands free and in possession of their weapons, she does not need a boon from anyone. No 21st century feminist can surpass her in being in charge of herself. Can we even imagine any woman having to suffer attempted disrobing with her husbands sitting mute; then facing abduction in the forest and having to countenance her husband forgiving the abductor; be molested again in court and be admonished by her husband for making a scene; then be carried off to be burnt alive; thereafter, when war is imminent, witness her husbands asking Krishna to sue for peace; and finally find all her kith and kin and her sons slain—and still remain sane?

An illuminating contrast is Shaivya, wife of Harishchandra. She does not utter a word when Vishvamitra drives her out of her kingdom, belabouring her with a stick because she is too exhausted to move swiftly. She herself suggests to Harishchandra that since she has fulfilled her function by presenting him with a son, he should sell her to pay Vishvamitra what he requires. When the Brahmana to whom she is sold drags her by the hair, she remains silent. This is precisely the conduct of a sati who utterly wipes out her own self and lives only in, through and for her husband.

The kanya’s personality, on the other hand, blazes forth quite independent of her spouse and offspring. She seeks to fulfil herself regardless of social and family norms. Thus, Draupadi does not rest till the revenge for which her father had invoked her manifestation is complete and the insult she suffered has been wiped out in blood. When she finds all her husbands, except Sahadeva, in favour of suing for peace, she brings to bear all her feminine charm to turn the course of events inexorably towards war. Pouring out a litany of her injuries, she takes up her serpent-like thick glossy hair and with tearful eyes urges Krishna to recall these tresses when he sues for peace. Sobbing, she declares that her five sons led by Abhimanyu and her old father and brothers will avenge her if her husbands will not.

Draupadi is the only instance we come across in epic mythology of a sati becoming a kanya. The Southern recension of the epic states that in an earlier birth as Nalayani (also named Indrasena), she was married to Maudgalya, an ill-tempered sage afflicted with leprosy. She was so utterly devoted to her abusive husband that when a finger of his dropped into their meal, she took it out and calmly ate the rice without revulsion. Pleased by this, Maudgalya offered her a boon, and she asked him to make love to her in five lovely forms. As she was insatiable, Maudgalya got fed up and reverted to ascesis. When she remonstrated and insisted that he continue their love life, he cursed her to be reborn and have five husbands to satisfy her lust. Thereupon she practised severe penance and pleased Shiva, obtaining the boon of regaining virginity after being with each husband. Thus, by asserting her womanhood and refusing to accept a life of blind subservience to her husband, Nalayani the sati was transformed into Yajnaseni the kanya.

In his 1887 essay Draupadi, Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay notes that Panchali is pre-eminently a tremendously forceful queen in whom woman’s steel will, pride and brilliant intellect are most evident, a befitting consort indeed of the mighty Bhima. He also points out that she represents woman’s selflessness in performing all household duties flawlessly but detachedly. In her, he sees exemplified the Gita’s prescription for controlling the senses by the higher self. Since a wife is supposed to present her husband with a son, she gives one to each of the Pandavas, but no more, and in that exemplifies the conquest over the senses, as in the case of Kunti. Once this duty is over, there is no sexual relationship between her and the Pandavas. That is why, despite having five husbands, Draupadi is the acme of chastity.

Ultimately, the fact that Draupadi stands quite apart from her five husbands is brought tellingly home when not one of them—not even Sahadeva of whom she took care with maternal solicitude, nor her favourite Arjuna—tarries by her side when she falls and lies dying on the Himalayan slopes, nathavati anathavat (husbanded, yet unprotected). That is when we realise that this remarkable “virgin” never asked anything for herself. Born unwanted, thrust abruptly into a polyandrous marriage, she seems to have had a profound awareness of being an instrument in bringing about the extinction of an effete epoch so that a new age could take birth. And being so aware, Yajnaseni offered up her entire being as a flaming sacrifice in that holocaust, of which Krishna was the presiding deity. This feature of transcending the lower self, of becoming an instrument of a higher design is what seems to constitute a common trait in these ever-to-be-remembered maidens. Remembering them daily, learning from them how to sublimate our petty ego to reach the higher self, we transcend sin.

THE KANYAS AND MODERNITY

The theme of loss is common to the kanya. Ahalya has no parents, loses both husband and son and is a social outcast. Kunti loses her parents and then her husband. Mandodari loses husband, sons, kinsmen. Tara loses her husband. Both have to marry their younger brothers-in-law who are responsible for their husbands’ deaths. Draupadi finds her five husbands discarding her repeatedly: each takes at least one more wife; Yudhishthira pledges her like chattel at dice; and, finally, they leave her to die alone on the roadside like a pauper.

Among the five, it is Ahalya who remains unique because of the nature of her daring and its consequence. She is the only one whose transgression becomes known and is therefore punished for having done what she wanted to. Because of her unflinching acceptance of the sentence, both Vishvamitra and Valmiki glorify her.

None of these maidens breaks down in the face of personal tragedy. Each continues to live out her life with head held high. This is another characteristic that sets the kanya apart from other women.

The kanya, despite having husband and children, remains alone to the last. This is the loneliness at the top that great leaders bear as their cross. Motherlessness characterises all of them—Ahalya and Draupadi have unnatural births, Kunti grows up without a mother, nothing is known of Tara’s mother. Mandodari’s mother, Hema, is just a name. The absence of a mother’s nurturing, love, and handing down of tradition leaves the kanya free to experiment, unbound by shackles of taught norms, to mould herself according to her inner light, to express and fulfil her femininity, achieving self-actualisation on her own terms. One is tempted to use a modern cliché to describe her: a Woman of Substance.

Writing about these kanyas, Nolini Kanta Gupta, the late scholar and secretary of the Aurobindo Ashram for half a century, says, very appropriately: “In these five maidens, we get a hint or a shade of the truth that woman is not merely sati but predominantly and fundamentally she is shakti.” He notes how the epics had to labour at establishing their greatness in the teeth of the prejudice that woman must never be independent, but always be a sati, known for her single-minded devotion to her husband. This, he says, is typical of the Middle Ages. The ancient relationship, he says, was the converse. In the Mahabharata, we find confirmation of the freedom enjoyed by women in the past. In the Adi Parva, when Pandu is persuading Kunti to have children by another man, he says:

“In the past, women/ Were not restricted to the house,/ Dependent on family members;/ They moved about freely,/ They enjoyed themselves freely./ They slept with any men they liked/ From the age of puberty;/ They were unfaithful to their husbands,/ And yet not held sinful…/ They greatest rishis have praised/ This tradition-based custom;… / The northern Kurus still practise it…/ The new custom is very recent.”

“We moderns also”, Gupta continues, “instead of looking upon the five maidens as maidens, have tried with some manipulation to remember them as sati. We cannot easily admit that there was or could be any other standard of woman’s greatness beside chastity.”

In the new millennium, are we too not moving cyclically towards a similar condition where the relationship between a man and a woman is not permanent and exclusive externally, where the sexes mingle freely, expansively, on equal terms, progressing towards fulfilling one’s potential? That is why the exhortation to recall the five virgin maidens is so relevant now. The past does, indeed, hold the future in its womb.

The author is a retired IAS officer, and a PhD in Comparative Literature for his research on the Mahabharata. He has authored and edited more than 30 books and published numerous articles in India and abroad on Public Administration, Comparative Mythology, Mahabharata, Homeopathy, Management and Human Values. The current article is an edited version of a piece published originally in March 2001 on the website boloji.com.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest