Movies

I Watched Shikara And Everything I Feared About The Movie Is True

- Shikara, while purporting to narrate the story of the exodus Kashmiri Hindus, ends up trivialising the story of their pain in characteristic Bollywood style.

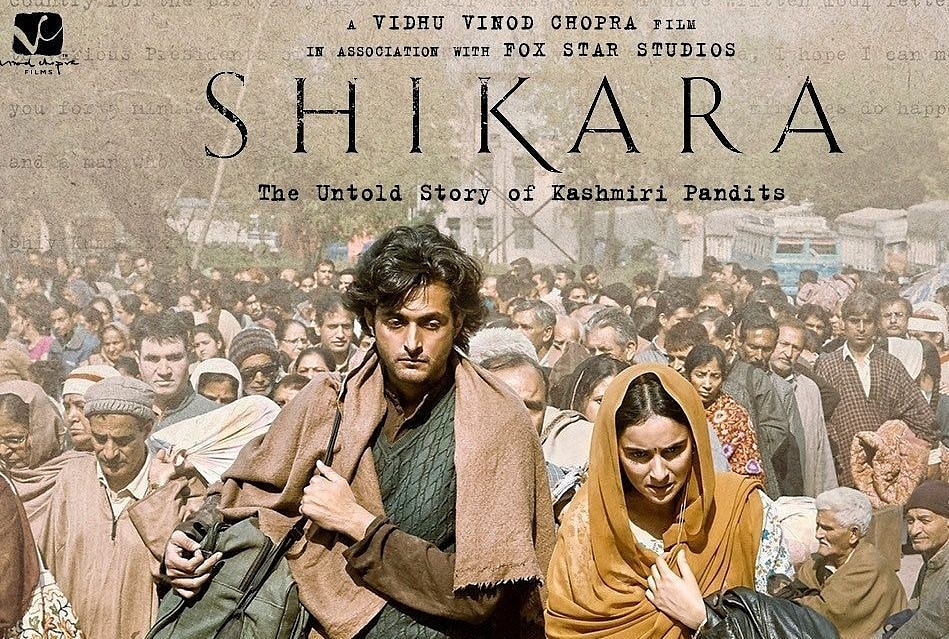

The poster of the film ‘Shikara: The Untold Story of Kashmiri Pandits’ (Twitter/@VVCFilms)

Shikara was sold to us as the untold story of Kashmiri Pandits. If the early teasers, trailers and Twitter outreach were an indicator, this was Bollywood’s first attempt at showcasing the crimes committed against the Kashmiri Hindus and their resulting ethnic cleansing from the Valley.

However, for a large part, the movie shies away from the brutal horrors the Kashmiri Pandits were subjected to in the late 1980s and early 1990s, especially the night of 19 January 1990.

A disclaimer would be in order here: this author was hesitant to watch the movie at first. Also, the review will contain spoilers, readers who have not seen the movie yet and plan to watch it may choose to stop here, please.

The story is told through the eyes of a Kashmiri couple, merry in their innocent love. The first few sequences of the movie focus on capturing the harmony that prevailed amongst the different communities that resided in Kashmir before the exodus.

We meet Shiv, a professor, and his wife Shanti. Shiv’s friend, Lateef, is a celebrated Ranji cricket player who makes it to the local newspapers for his ‘hurricane hundreds’. Also, we meet Aarti, Shanti’s friend. Lateef confesses his love for Aarti on the day Shiv and Shanti are getting married.

The story moves on from the innocent romance of the couple to the tragedy when Lateef’s father, a local party-worker for a state political party, is hurt in a clash with the police.

The injuries Lateef’s father sustains result in his death. However, we are not given any information about the clash between the party workers and the police, what caused the clash in the first place, or why did the police resort to violence. The death is attributed to the police or the state action without any credible explanation and the story is conveniently pushed forward.

What follows is a series of apologetic sequences.

Lateef, driven by the grief of his dead father, walks away from a career in first-class cricket to the life of a terrorist. Facilitating the kidnapping of his own friend Shiv from his college, he brings him to an isolated hideout to warn him against the imminent violence that was planned to be unleashed against the Hindus in the valley — “Indian agents”. The warning is projected as one coming from a friend to a friend. Of course, we are supposed to ignore the thousands of Kashmiri Hindus and their families who were not recipients of such a ‘friendly’ warning.

This is just one of the many examples where the story chooses to divert away from the brutal reality. Terrorists looking to rip apart Kashmiri Pandits are termed as ‘few boys up to mischief’ by their neighbours from the majority community.

What comes as a major disappointment is when the story moves to the night of 19 January 1990. The horrors, crimes, rapes, and murders, all the atrocities that have been documented, are skimmed over with convenience that is both shocking and absurd.

The sloganeering of the terrorists, the men with a clear-cut objective of burning down Hindu homes, is drowned in a needless background score. The insurgents, in one of the critical scenes, are not even properly shown, and the story portrays them as mere shadows as if to shield their faces, their names, the identity, and their ideology. It portrays them as if they almost did not exist.

The violence that was unleashed against the Pandits is carefully ignored as if it was just a few scattered incidents. The aptest description of violence against the Kashmiri Pandits is an aerial shot of smoke presumably from their burned homes (one can count 3-4 homes amongst the scores within the frame).

The escape of the Kashmiri Pandits is purposefully reduced to a scene where the protagonist’s family is seen being helped by a Muslim family, and that’s all we are told about the escape before the scene cuts to hundreds of Kashmiri Pandits are stranded on a highway.

In the garb of the protagonist’s wife trying to save her apple tree and the temple within the house, the story trivialises the threat Kashmiri Hindu women faced in those days. It is widely known that many were raped and killed.

There is also a jibe at the slogan of ‘Mandir Wahin Banyenge’, an attempt to dilute another sensitive matter. It’s as if the filmmakers wanted to examine the extreme they could go to in being carelessly ‘’unserious’ about the story they were claiming to tell.

In the latter part of the movie is a sequence that seriously tests the patience of its audience. We meet Lateef, 18-years after 1990, a terrorist who proudly claims killing men of the Indian Army. He follows it with a monologue to justify the violence, attributes it to the leaders in Delhi, and then goes on to mention the killing of the Kashmiri Pandit woman he wanted to marry — Aarti.

Right after this, the protagonist tells Lateef that he will soon be fit enough to play cricket again.

The only truthful element of the story is the part where the protagonists visit their house in Kashmir. Even in its shoddy camera work, that one sequence, to some extent, documents the cleansing of the Pandits from the Valley.

To sum up, the state is portrayed as the bigger enemy here. Everyone is shown in despair, but the story behind this despair, behind this helplessness, is omitted. Those in despair are without a voice because of the political correctness the filmmakers choose to resort to.

‘Few boys up to mischief’ did something and over 400,000 Kashmiri Pandits had to leave their homes, we are told.

The movie is so predictable that you can see the potholes in this story from a mile away, yet so unpredictable that you will be amazed by the pseudo-secularist diversions it takes at almost every second sequence, leaving you jolted in anger and exasperation.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest