News Brief

Hijab Case: Court Should Not Embark Upon The Task Of Interpreting Quran, Says Counsel For Petitioners Calling It ‘Highly Objectionable’

- A petitioner counsel said in the SC that constitution clearly provides that Court should not lay down religion for people to follow and should not interpret religious scriptures.

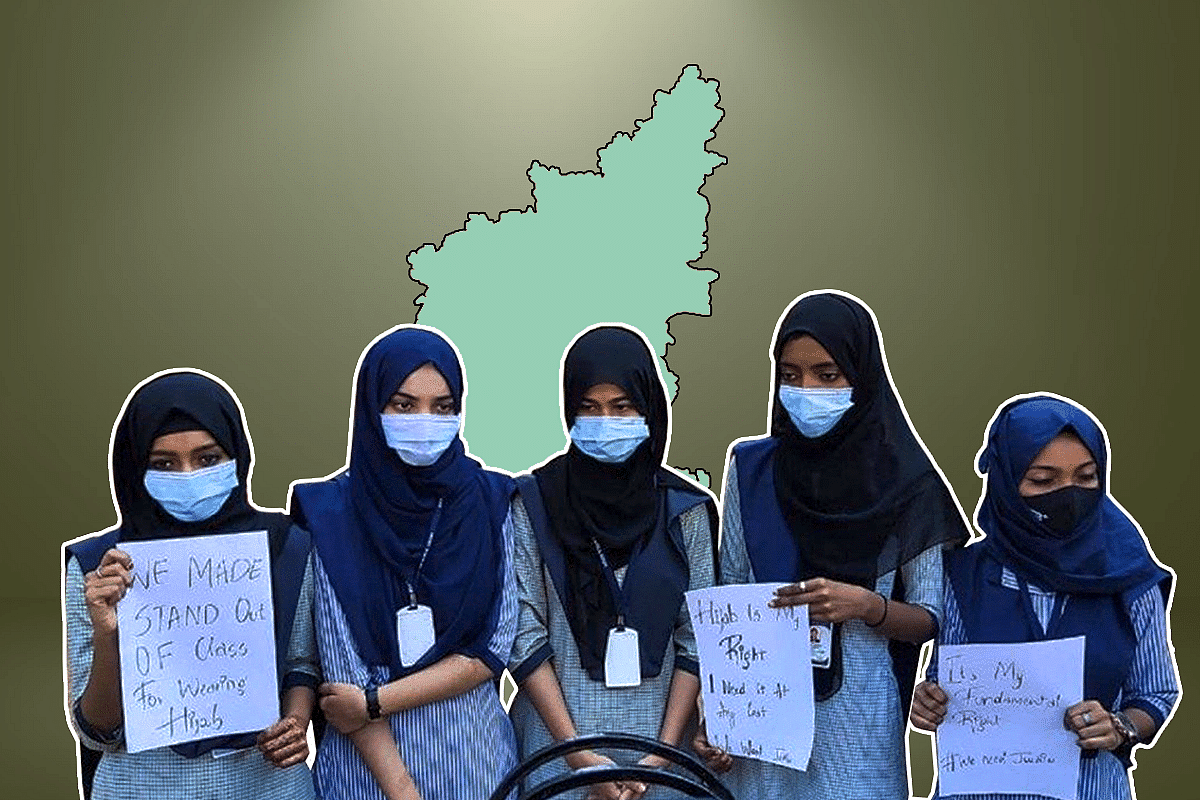

Karnataka Hijab Row

The Supreme Court was told by one of the counsels arguing in the Hijab case that the Karnataka High Court’s act of ‘interpreting the Quran‘ was ’very objectionable’.

A bench of Justices Hemant Gupta and Sudhanshu Dhulia is hearing a batch of petitions challenging the prohibition of sporting the Hijab in educational institutions in Karnataka.

Senior advocate Yusuf Mucchala told the apex court, as reported by Live Law, that there are ’well settled rules of interpreting Quran, with which the Courts are not equipped with’.

Explaining the ‘objectionable act’ to the bench on day 4 of the hearing on Monday (12 September), Mucchala said:

‘It has been held that there cannot be any interpretation of this court of the Al Quran or using one interpretation against another. This is what High Court has done,’ as quoted by Bar and Bench.

Adding further he said, ’Al Quran is Arabic and the courts in India are equipped to adjudge. Even average Indian Muslim reads Arabic as is without the meaning. Thus, in such cases the court should not embark upon the exercise of interpreting Quran’.

He added, as reported, that the constitution ’clearly provides that Court should not lay down religion for people to follow‘ and that the Court should not interpret religious scriptures.

To this Justice Dhulia asked what ’option does the High court have’ when the petitioners went to it claiming it as an essential religious practice.

‘High court gives a decision one way or other and you say it cannot be done,’ said Justice Dhulia.

To which Mucchala responded saying while ‘somebody must have done it erroneously in enthusiasm’, the ‘court should know its limits’.

When the bench pointed out that the counsel was contradicting himself since he had sought it be referred to a larger bench, Mucchala said the essential religious practice must not be invoked in a case of individual right and that ‘somebody must have wrongly applied’.

Mucchala also added that the ‘issue which is to be seen is whether it is essentially religious or essential to religion’.

Before he concluded, he said though some of the petitioners had put the question before the court, the 'court should have said hands off' and that it cannot decide whether it was an essential practice or not.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest