Politics

Can A Case Be Made For President’s Rule Under Article 356 In West Bengal?

- Interestingly, in 2007, Mamata Banerjee was demanding the use of Article 356 against the then chief minister(CM) Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, citing events where the CM’s party was terrorising the state and using government machinery to intimidate and attack the voters.

- Almost 14 years later, the state finds itself in the same position.

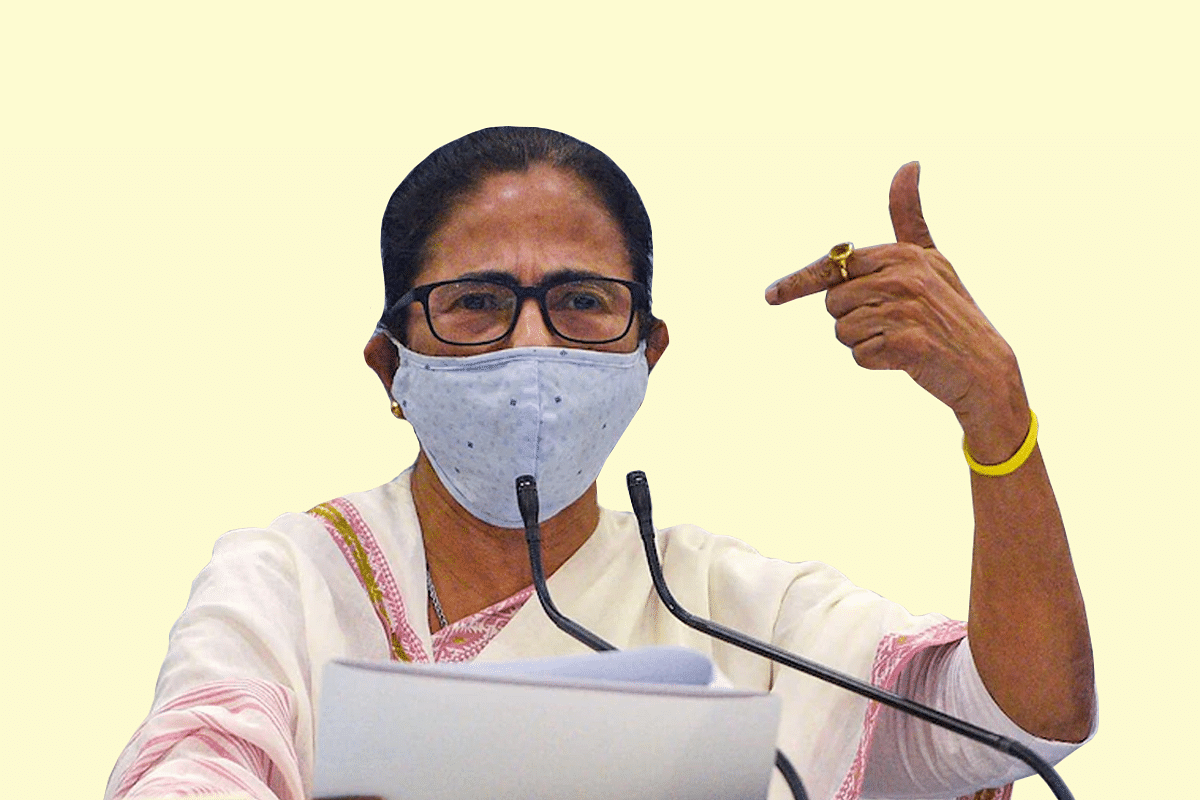

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee

Following the declaration of the state assembly election results in West Bengal on Sunday (2 May), violence has erupted in many areas with the workers of the Trinamool Congress (TMC) going on a rampage against supporters and workers of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

On social media, videos and images surfaced of many BJP offices within the state being vandalised and workers being attacked. In Birbhum, BJP spoke about two women poll agents being gang-raped and many being molested.

Photos have also surfaced of the mortal remains of a BJP worker who was killed in the violence along with women being beaten on the roads, wards being vandalised, shops being burned in Bara Bazar, and houses of the workers being attacked.

On Sunday evening, Avijit Sarkar, a BJP worker from Ward no. 30 in Beleghata in Kolkata, was lynched by the TMC workers.

In a video that was uploaded on Facebook by Sarkar only a few minutes before the lynching, Sarkar spoke about the TMC workers who slaughtered his pets.

In a tweet last evening (3 May), Swapan Dasgupta, a former member of the Rajya Sabha, stated more than a thousand Hindu families were out in the fields to escape the mobs seeking to attack the BJP supporters. There were also additional reports of women being molested in the area. In his tweet, the former MP was seen requesting Amit Shah for additional security.

With reports of violence coming from multiple parts of the state, the question of Article 356 is now on the table. While none of the ministers and spokesmen has advocated President’s rule in the state, the constitutional option could be explored to curb the TMC violence.

The question came up after West Bengal Governor Jagdeep Dhankar summoned the DGP of West Bengal Police along with Kolkata Commissioner in the afternoon on Monday. The governor also tweeted about nine people losing their lives in the violence. Later in the day, the BJP state media cell published the name of six of those workers.

The governor also tweeted about his interaction with Mamata Banerjee and reiterated the concerns around the post-poll-violence, arson, looting, and killings, further speculating the possibility of President’s Rule.

Article 356 of the Constitution of India is based on Section 93 of the Government of India Act, 1935. Citing the failure of constitutional machinery and mechanisms within the state, President’s rule can be imposed.

If the President gets a report from the state’s Governor where it states that the government cannot carry on the governance according to the provisions of the Constitution, there are grounds for President’s rule under Article 356.

Also, under Article 365, the President’s rule can be applied to any state that fails to comply with the directions given by the central government. However, in the case of West Bengal, Article 356 is relevant.

Post the application of Article 356, the governor carries on with the administration of the state as a representative of the President. The legislative assembly stands suspended or dissolved by the President.

Almost all states have seen the imposition of the President’s Rule, with West Bengal witnessing the imposition four times.

With time, strict guidelines were added to ensure a system of checks and balances for the use of Article 356.

The apex court noted that the proclamation of the President’s Rule is subject to judicial review, must be justified by the centre, leaves the court with the option to reinstall the dissolved state government, and that serious allegations of corruption or financial instability cannot be the grounds to impose Article 356.

In the landmark judgement, the court noted that the imposition of Article 356 must not be against the strengthening of secularism within the state.

All in all, the court, in order to crack down on misuse of Article 356, singled it out as an exceptional power. Even the Sarkaria Commission Report in 1983 outlined the use of Article 356 as an exception, not a norm.

There have been commissions suggesting alternative ideas to Article 356 as well. For instance, the Punchhi Commission recommended that the centre should only focus on a troubled area and bring it under its jurisdiction instead of the entire state. The commission stated that the takeover of a troubled area must not last beyond a few months. The idea of a localised emergency was floated.

However, in a recent judgement, the apex court stayed the order from the Andhra Pradesh High Court that was attempting to seek Y S Jaganmohan Reddy’s government's response on an alleged constitutional breakdown in the state.

The Supreme Court labelled the order as ‘disturbing’.

Arguing for the Andhra Pradesh government, Solicitor-General Tushar Mehta argued that the power of Article 356 was vested in the executive and could not be exercised by the judiciary.

The challenge, however, with the idea of imposing Article 356 in West Bengal, would be on deciding the grounds for the phrase ‘the government of the state cannot be carried on in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution has been ambiguous in its interpretation. Reference to Articles 256, 257, and 355 must also be made in this regard.

For the BJP to make a case for using Article 356 in West Bengal, strong evidence would be required for the satisfaction of the governor, and consequently, the President, and also once it is challenged in the Supreme Court.

Also, the violence that is going on in West Bengal right now cannot be equated to a routine law and order situation, for voters are being hunted by workers of the other party, and while it constitutes a violation of fundamental rights, it also indicates a far more serious situation on the ground.

The caretaker government under Mamata Banerjee has been abysmal in its dealing with the violence so far, so the grounds for Article 356 imposition stay strong. The BJP was also under pressure last year as the violence increased in the run-up to the campaign to use Article 356.

Interestingly, in 2007, Mamata Banerjee was demanding the use of Article 356 against the then Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, citing events where the CM’s party was terrorising the state and using government machinery to intimidate and attack the voters. Almost 14 years later, the state finds itself in the same position.

Beyond making a case for Article 356 in West Bengal, the BJP must manage the narrative in the media as well. Here, two huge challenges await the party.

Firstly, putting a brake on the infamous normalisation of political violence in West Bengal. Even in the last 48 hours, most arguments have been about dismissing it outright as routine. For the party now with more than 70 seats in the state assembly, and 18 MPs, the aim must be to expose the one-sided violence in the state, demand curbing, and consequently reset the state politics.

Secondly, the challenge will come from the usual political suspects who would blame the government for avenging the election defeat. From an optics point of view, the government may be seen as meddling in the internal affairs of a state while losing the battle of Covid.

If the failures in handling Shaheen Bagh and Singhu Border protests are any indicators, for the Narendra Modi government, especially Home Minister Amit Shah, the biggest test begins now.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest