Politics

Delhi Elections 2020: Unless AAP Vote Share Shrinks More Than 15 Per Cent, Kejriwal Is Set To Make A Comeback

- Unless AAP loses over 15 per cent of its vote share, and most of that to BJP, Kejriwal looks set to return as Chief Minister for another term.

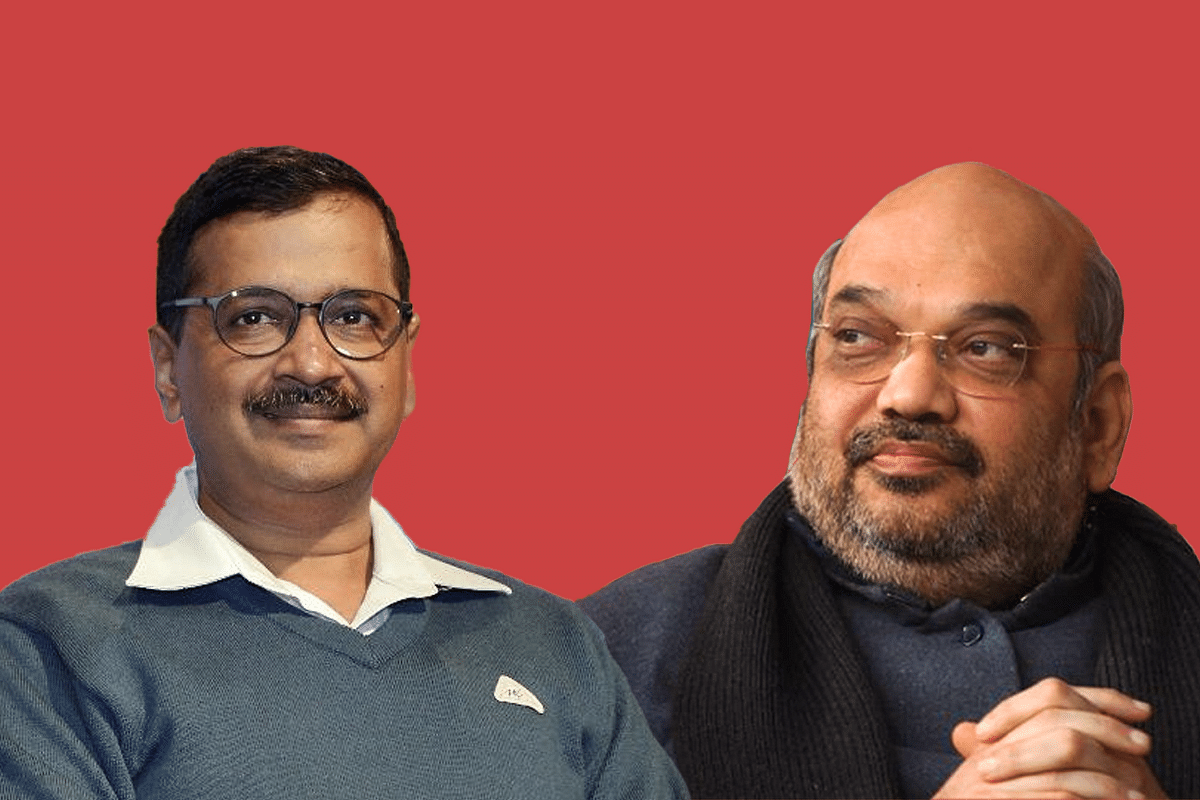

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal (left) and Home Minister of India Amit Shah.

Delhi — India’s only city-state, will elect a new legislature in February. It is a firm citadel of Aam Admi Party (AAP), led by Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal. The party won 67 out of 70 seats, and 54 per cent of the popular vote, in 2015.

Electoral forecasting is skewed in Delhi, because its residents vote very differently in provincial and national elections.

In both 2014 and 2019, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) swept all seven Lok Sabha seats with commendable margins. To compound predictive issues, both the 2013 and 2015 assembly elections were tri-partite affairs, with the Congress party progressively losing a substantial portion of its traditional vote base to the AAP.

As a result, the BJP held on to its assembly vote share, but won only three seats in 2015; and, in most cases, AAP victory margins shot up to over 20 per cent.

Under such circumstances, trying to figure out which set of votes might move which way, where, and to whom, becomes a guessing game — exciting for psephology geeks, but imprecise.

Consequently, it makes more sense to study the impact of a vote swing away from AAP, because it is the dominant party both in terms of vote shares and victory margins. Such an approach also aids in testing the validity of a recent opinion poll by ABP News for Delhi.

The numbers are:

The first step then, is to tabulate the 2015 results seat-wise, and conduct sensitivity runs on possible changes in AAP victory margins due to negative vote swings away. By this approach, the principal question, of who the beneficiary of that vote swing might be, is taken out of the equation. This is also, indirectly, an indicator of just how large the 2015 mandate was for the AAP.

Four runs were made on AAP victory margins, to simulate AAP results, at different magnitudes of vote swings away from the AAP.

The outcomes are interesting:

As the graph below highlights, the AAP position appears robust enough to weather even a 15 per cent erosion in vote base. What this means is that the AAP would be able to garner a simple majority even if it loses a bulk of the new votes it collected in 2015, on account of the size of their victory margins.

Interestingly, what this analysis also indicates, is that the projections remain the same, irrespective of whether AAP votes shift to the BJP, or the Congress, or both.

However, a clear inflexion point is seen: beyond a 15 per cent negative vote swing, the AAP starts to lose seats more materially. And yet, even at this stage, because of the first-past-the-post system, the AAP could, technically, still manage a higher seat tally if the vote-shift away goes more to the Congress than to the BJP.

But will that happen? The recent ABP News opinion poll doesn’t think so.

According to its poll, the AAP largely holds on to its 2015 vote share but gets eight seats less than the last elections. The Congress continues to bleed votes, coming down to a stunning 5 per cent, and the BJP too, is shown to lose 7 per cent of the vote share from 2015.

This doesn’t make sense numerically or electorally, because the poll forecasts vote shifting from the BJP and Congress to ‘Others’.

At the same time, both the BJP and Congress’ seats go up, while the AAP’s seat tally comes down. It might have made some sense if the 16 per cent ‘Others’ component was classified as the undecided vote, but to assign 16 per cent to ‘Others’, when past state results give only 3 per cent to ‘Others’, appears to be a glaring incongruity. In addition, at no place has the poll specified who these popular, phantom ‘Others’ are.

How can the BJP’s seat tally go up from three to eight when it loses 7 per cent of its vote share to Others (meaning that the AAP victory margins not only remain intact, but actually improve)? How can the Congress improve from zero to three when its vote share falls by half to 5 per cent? And why would the AAP lose eight seats when the poll predicts that its vote share will remain essentially undisturbed?

Obviously, one interpretation is that the poll perhaps represents an electorate in flux; a citizenry still in the process of making up its mind.

Consequently, one may conclude only with a qualitative assessment:

Unless the AAP loses over 15 per cent of its vote share, and most of that to the BJP, Kejriwal looks set to return for another term as Chief Minister.

In which case, making BJP the capital’s bogeyman won’t make the Congress Delhi’s favourite — not by a long shot.

Ergo, the ongoing, orchestrated protests, sit-ins and vandalism will not benefit the non-BJP, non-AAP forces electorally. Their efforts are wasted. Meaning, it’s time the ‘freedom brigades’ went home, and time for normal, civilised electoral service to resume.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest