Politics

Hindu Democracy, Punyabhoomi And The Idea Of Bharat

- A 'right wing force' — which BJP is oft called — is an epithet rooted in short-sightedness. What the party really stands for is 'liberal conservatism'.

- Here's why.

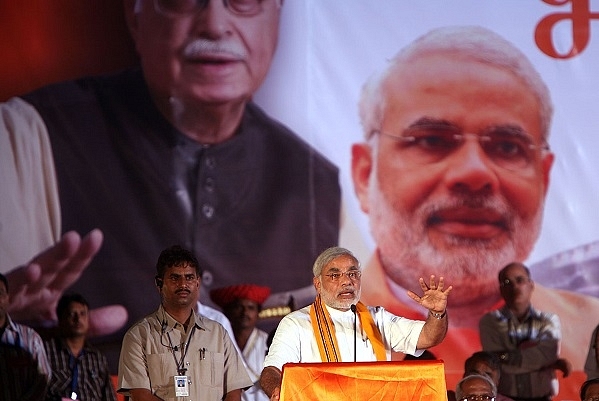

Narendra Modi during a rally.

In my previous article, I described the BJP as a Hindu Democratic Party, in an evidence-based manner by interpreting their recent record of legislative and executive actions.

On this basis, it was demonstrated that they do not even qualify to be considered a traditional right-wing or even traditionally conservative party.

Among interesting feedback to the article was confusion that it implies the BJP is like the Democratic Party of the USA.

This view is wildly off the mark, but it underscores that the default Indian political understanding broadly divides politics into modern liberalism (akin to the US Democrats/British Labour) and traditional conservatism (like the US Republican Party/British Conservatives).

This is a very narrow binary view that does not reflect the reality of Indian politics at all.

A second and very pertinent piece of feedback is that the original article appears to impose a western construct (Christian democracy) upon India. However, that’s not quite the case, as this article describes.

Christian democracy is simply an umbrella term for a range of European parties who all have a common imperative with the BJP — the preservation of a homeland safe for their faiths, while also maintaining a functional modern democracy, i.e. not a theocracy.

Hindu Democracy : A Form of Liberal Conservatism

The BJP’s recent legislative record is wide ranging. Some laws address core political objectives: the elimination of Article 370 and the CAA law and the pursuit of UCC.

Others address reformist goals like the farm laws, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, and the GST. Other recent legislative actions are very liberal minded — supporting workers compensation rights, consumer rights, maternity care and abortion rights and transgender rights.

In political science, this is liberal conservatism. The conservative basis is forward looking — it just values orderly evolution that focusses on preserving the basic cultural fabric of the land.

If the underlying basis is too rigid, it becomes a right wing traditional polity or theocracy, instead of a liberal conservative entity. Hinduism is a forward- looking religion that enables this.

There is no ‘compromise’ or ‘hypocrisy’ in liberal conservatism. The BJPs support, for example, of maternity, abortion or transgender rights is not driven by the modern feminist or LGBT movements.

Those groups are not sole guardians of these rights. Rather, it reflects the fact that Hinduism itself respects women and has never been antagonistic to the third gender; the western approach to these is alien to India; the factual legislative record shows that the BJP has evolved its own independent, native liberal doctrine.

Arguably, the Anglophone liberal versus conservative dichotomy reflects the lack of evolution of polities in both the US and UK, as compared to India.

This backwardness of their politics shows up in the pronounced polarisation of their local politics. Modern democracies in lands with strong cultural moorings have often tended towards liberal conservatism — the BJP in India, the Christian Democrats in Germany, Austria and Italy, the LDP in Japan, the Liberal Party in Australia being examples.

Neither the US nor UK have a political party that is avowedly liberal conservative; the only significant party of the kind in the Anglosphere is the Liberal Party of Australia (LP).

The LP’s conservatism in Australia was primarily racial — Robert Menzies, who was their Prime Minister from 1949-1966, was a strong supporter of the White Australia policy.

The term Hindu Democratic Party is derived from the most well known mainstream form of liberal conservatism involving religion and native culture as a base — Christian democracy in Europe.

But why associate the BJP with a western construct at all? This is a very good question. Several features of the western political spectrum simply do not apply to India. Such terminology cannot be carried over wholesale without any nuance.

However, we live in a global world today. As India grows in power and influence, we interact more with the world. It is important to understand how politics is interpreted by the outside world, and to have a well considered description of Indian political mainstream using a best approximation, even if the association cannot be perfect.

Liberal Conservatism: The Dominant Politics of Strongly Rooted Cultures

An interesting behaviour seen post-World War 2 is that all modern democratic nations that have either strong religious or native cultures, or are the punyabhoomi of major faiths, have all developed liberal conservatism as the principal local political form.

In Germany, Konrad Adenauer’s CDU came to power in 1949, and dominated German politics, having collectively ruled for over 50 of 70 years.

Besides Angela Merkel and Adenauer, Helmut Kohl and Ludwig Erhard are famous Christian Democrats; Merkel and Erhard were practising Lutheran Protestants, the other two Catholics.

In Italy, Alcide de Gasperi’s Christian Democrats came to power in 1946, and that party continuously ruled until 1981, and then came back to power again a few times.

In Israel, the Likud Party has been the dominant political force since the 1970s, with leaders like Menachem Begin, Ariel Sharon and now Benjamin Netanyahu being Likud leaders.

In Japan, the Liberal Democratic Party has dominated postwar politics. Everyone from first PM Shigeru Yoshida to Hayato Ikeda — famous for driving their postwar economic miracle — to Shinzo Abe were LDP leaders.

In Ireland, a Catholic bastion, the Fine Gael and Fianna Fail — founded by their longest serving leader Eamon de Valera — have dominated politics.

All these parties have something in common — they are liberal conservative ones, and the majority classify themselves as Christian Democratic. Italy and Ireland are homes of Catholicism. Germany the home of Protestantism/Lutheranism, Israel the Jewish homeland and Japan the home of Shintoism.

It is not a coincidence that they all developed analogous polity right upon foundation.

The organic rise of the BJP is a similar story. From a more traditionally conservative origin in the Bharatiya Jan Sangh days, it evolved into a more right wing populist entity and rapidly gained a stable vote share of at least 20 per cent in every general election.

Over the past two decades, it has solidified itself as the principal political pole of India.

Neither the US nor UK have a native faith. While there is a Church of England, that is simply the result of a political split — King Henry VIII wanted an annulment but the Vatican wouldn’t grant one. So he split and created his own church for convenience.

The US is a young frontier country with a stagnant two-party system.

Hindu Democracy: A Liberal Conservative Approach to Dual Imperatives.

Countries that are both a democratic society and the home of a major faith realise that they also safeguard that faith, while simultaneously managing the uniform policy imperatives of being a modern democratic society.

They all maintain legal secular rights for individuals. However, they all make it clear that politics serves the culture, and not the other way around. Therefore, the dominant culture will always receive a first-among-equals treatment by polity, even when individuals from different faiths are treated alike from the perspective of basic law.

This distinction arises from the fact that politics does not hold a land together. Its culture does. India has a dominant culture that’s readily visible to everyone from a natural born person to a stranger looking from outside in.

That culture is Dharmic. India safeguards Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism.

The power of Dharmic culture over polity has demonstrably manifested itself in the fact that the moment the artificial basis of Nehruvian western liberal-socialism weakened, the BJP’s liberal conservative polity took hold rapidly within less than two decades.

It has since cemented itself under Narendra Modi, while the Congress has been reduced from over 75 per cent of Lok Sabha to under 10 per cent — essentially a large regional party.

A country that had no other basis for socio-political cohesion would simply have fallen apart into civil war, as many countries have. Had India lacked such a basis for cohesion, the end of the Congress would have been the end of the political nation state of India.

However, that did not happen. India has instead politically united into the strongest form in several decades. So much so that assorted wags hyperventilate that India is ‘authoritarian’.

Why Did The BJP’s Emergence Take So Long ?

Given this political history, a question remains — if countries with such strong religious and cultural foundations took a common approach, why didn’t India do so at its inception?

At this point it might be somewhat clear — it almost did. People like Sardar Patel and S P Mukherjee advocated this path.

One can take a look at the dire situation in 1948-50: Muladi massacre, Barisal riots, Anderson bridge massacre, Sitakunda massacre and more just in Bengal, with even more in Punjab.

Each day brought more grim news.

S P Mukherjee, among others, argued strenuously for a population transfer. Objections to this included the difficulty of transferring crores of people, treatment of property and more; those in favour argued that at least non-Muslims must be allowed to move to India.

Nehru opposed this, with fatal consequences for millions of Hindus. The arguments came to a head when S P Mukherjee quit the government during the Nehru-Liaquat Pact and founded BJP’s predecessor — the BJS.

Mukherjee later died in custody while protesting the imposition of Article 370. Sardar Patel’s demise preceded Mukherjee’s. With its brightest leaders gone, the BJP took another generation to become a political force.

It has not looked back since.

The BJP retains a historical memory of its foundation. Its first two acts upon acquiring the 2019 mandate that gave it reasonable strength in both houses of Parliament, were to deal with two items its founder fought over — eliminating Article 370 and passing the Citizenship Amendment Act, which serves to fulfill at least partly, the goal of enabling non-Muslim refugees from partition era lands the ability to gain citizenship in India, as Amit Shah explained.

The current position of strength within Indian polity gives the BJP the opportunity to cast the future of Bharat in the terms it should have always been.

This land is the sacred land and guardian of not merely one but multiple great faiths — Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism.

The guardianship of this history and culture cannot be sacrificed at the altar of tactically expedient identity politics. There is much to be done, but it must also be acknowledged that the BJP has been true to its history, and remains the only national party that understands and has the dedication to accomplish the political goal of ensuring that India remains a place where its native faiths and culture can flourish.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest