Politics

It’s Time For Modi To Do A Vajpayee On Reforms; It Will Silence Foreign Critics Of Article 370 Move

- If Modi is to seize the initiative and silence his foreign critics and help India reverse the current slowdown, he has to do a Vajpayee.

- This is the right time for staking a claim to the title of India’s biggest economic reformer since Narasimha Rao.

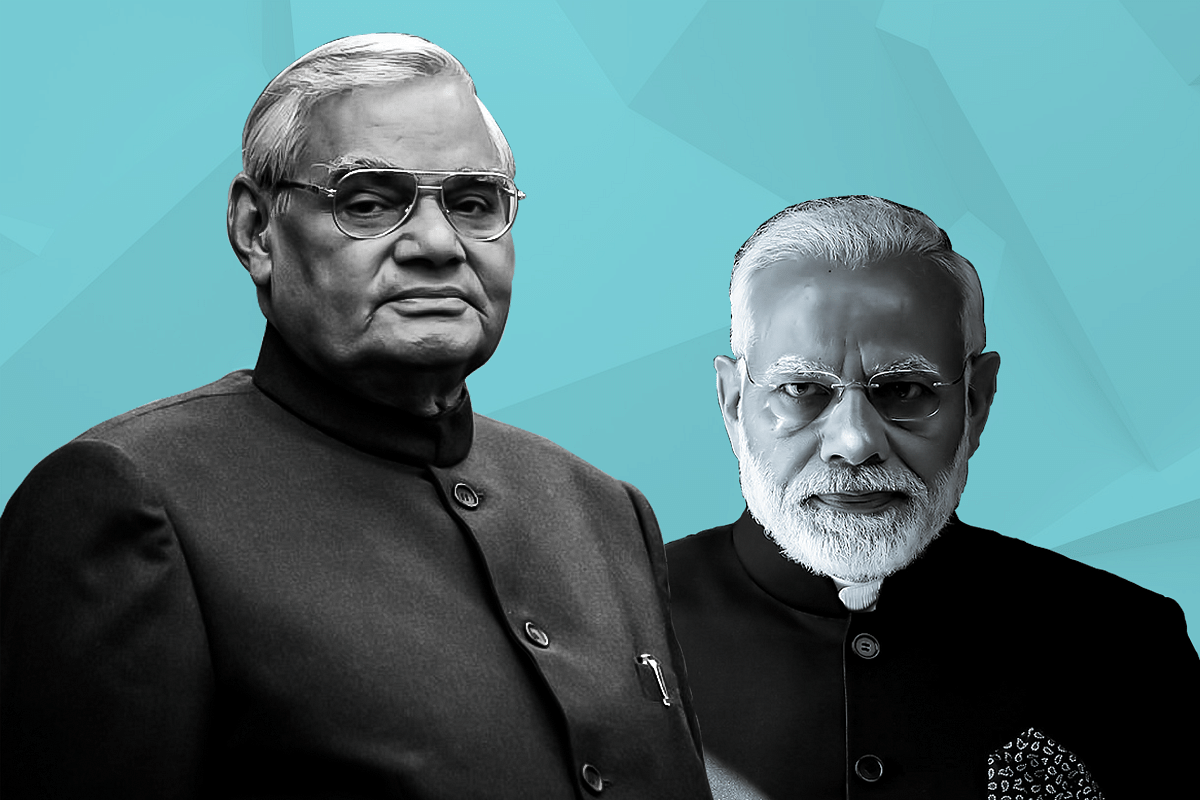

Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi.

The spate of anti-India news in Western media, precipitated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s bold moves to end Jammu and Kashmir’s isolation by extending the Indian Constitution to that border state, should be used as a goad to push bolder economic reforms.

If Modi and Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman use this opportunity to do this, all this agenda-driven Western propaganda against India will come to naught. Western critics are essentially hypocrites; if they see an economic benefit from reform, they will support the worst autocracies (China, for example), and alter their opinions.

In this, Modi could take a leaf out of Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s notebook.

After the 1998 Pokhran-II blasts, India was in the international doghouse as the then US president Bill Clinton imposed sanctions, and India additionally faced an economic slowdown. After the dotcom bust of 2000, Vajpayee was faced with two choices: continue to fight India’s isolation diplomatically, or take up reforms to overcome both the sanctions and revive the economy.

Vajpayee launched the Golden Quadrilateral highways development programme to boost infrastructure investment and also privatised many public sector companies (VSNL, IPCL, Balco, Hindustan Zinc and Centaur Hotels).

Controlling stakes in Maruti were handed over to Suzuki for a hefty premium. The Electricity Act was amended to allow consumers to shift away from their current suppliers, and bankrupt state electricity boards were given a lifeline by converting their overdues to bonds.

People today remember Vajpayee for his reform, but not the circumstances that forced him to embrace them with a vengeance. It was the prospect of being reduced to a global pariah after the post-Pokhran-II sanctions that made this a priority.

Also, the domestic infrastructure push was necessitated by the post-Nasdaq global recession and domestic slowdown.

Put simply, Vajpayee’s reforms were as much prompted by necessity as conviction. The same as P V Narasimha Rao’s in 1991.

In Modi’s case, he is a committed reformer in some areas – the goods and services tax, the insolvency code, the direct benefits transfer subsidy delivery reforms are some examples – but he is less gung-ho about privatisation.

In the post-Article 370 scenario, where some countries like Britain, not to speak of China, are willing to take an anti-India line, the strongest response will not just be effective diplomacy, but economic opening up.

Last week, the government liberalised rules for shares with differentiated voting rights (DVRs), by eliminating the 26 per cent limit for DVRs after a new issue of capital. The condition of three years of profitability has also been removed.

While this is expected to help promoters of startups to retain their ownership of companies even after inducting fresh capital from private investors, this change could also facilitate the sale of government companies while formally retaining a controlling stake.

In the budget, the Finance Minister said that the government was open to reducing its stake to below 51 per cent as long as there were other public sector entities holding some of the shares.

However, this makes little sense except as a stopgap. It means other public sector entities will be stuck with shares they cannot ever sell.

A far better way would be to dilute the government’s economic stake and hand over management to private promoters in public sector companies even while retaining 51 per cent voting power in the short term.

This will – in the interim – allow the government to keep the unions in good humour. At some point, though, government has to change the law to allow for a formal and effective strategic sale without retaining control.

It is worth recalling that Vajpayee’s privatisations came to a dead halt when the unions and politicians opposed strategic sales of Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum. They challenged the privatisation of ownership when the laws nationalising them had not been changed.

The DVR law should allow for effective change, with the legislative changes to follow after the event. But it is still best to change the law first, privatise next.

If Modi is to seize the initiative and silence his foreign critics and help India reverse the current slowdown, he has to do a Vajpayee. This is the right time for staking a claim to the title of India’s biggest economic reformer since Narasimha Rao.

It should also be satisfying to call the bluff of Britain, China and other countries trying to fish in the troubled waters of the Dal lake.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest