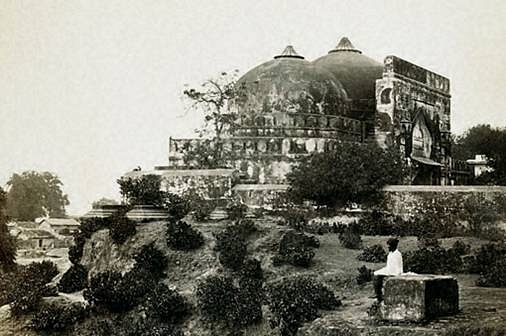

The author had been in Ayodha on 6 December, 1992, watching the domes of the Babri Masjid fall. She revisited the town 17 years later, almost to the day. Today, on the 22nd anniversary of one of the most historic events of post-Independence India, she remembers the various Ayodhyas she encountered.

Apparently, Bharatiya Janata Party workers in Ayodhya and Faizabad are planning to mark December 6—the anniversary of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992—as Bhagwa Divas (Saffron Day), with saffron flags on temples and homes, and lights and diyas. (Party leaders are supposed to be frowning on this.) Will this resonate with the Ayodhya I saw in 2009, I wonder.

That was an Ayodhya with a Ram Lalla Mobile Store run by a 20-year-old Muslim.

An Ayodhya where a 20-something Hindu, whose family runs a mutt, told me, “Roti mil jaaye, to Ram kya, mein to Shyam aur Ravan ka bhi naam japne ke liye tayyar hoon (If I get roti, I am ready to chant the names of Ram, Shyam and even Ravan.).”

An Ayodhya where a Muslim taxi driver, whose house is right next to the barricades protecting the disputed site, said he wants the Ram temple to be built—it will get him more business. He regularly transports people from Faizabad railway station to the temporary structure housing the Ram Lalla idols at Ayodhya and helps them with other logistics of the actual darshan.

An Ayodhya where the administrator of a mutt complains, not about a grand temple not being built, but about drains and garbage.

I had been sent to Ayodhya by the newspaper I was then writing for soon after the report of the M.S. Liberhan Commission that enquired into the demolition was made public.

Strangely, the dates and days I went there were the same as they were 17 years earlier, when I had first gone to Ayodhya. I reached Faizabad (the twin town, seven km away) on 1 December, as I had done in 1992. It was a Monday, as in 1992. I checked into the same Sham-e-Awadh hotel that had been home to the press corps in 1992. The reception and dining hall seemed the same. The rooms, however, were new and swanky. But when I picked up the phone to make the first calls, I discovered that I had to go through the operator, as in 1992. The hotel still didn’t have direct dialling! On deadline day, I asked to be shifted to a quieter room. When I entered the room in the front of hotel, it was like stepping back in time. Nothing had changed. It could well have been the room I had occupied in 1992.

But Ayodhya had changed, I realised over the next two days I spent there.

As I drove by the heavily barricaded and fortified 74-acre disputed area—encompassing the hillock where the Babri Masjid had once stood, I was transposed back to the morning of 6 December 1992.

As I headed towards Ayodhya from Faizabad early that fateful Sunday morning, I was not in the best of moods. I was working for a Sunday newspaper then and my report was the only one to say that there would be some action beyond the symbolic puja that other newspapers had reported. That was because I had filed my piece on Friday (the day the paper went to press) based on statements of the late Acharya Giriaj Kishore, then the joint general secretary of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and other mahants at the vanguard of the Ram Mandir movement while other papers had carried reports based on a press conference on Saturday where these worthies seemed to have made a U-turn. Mine appeared to be the only wrong story.

Indeed, barring some provocative slogans from some sections of the crowds in Ayodhya, there was nothing to indicate that things would go horribly wrong some hours later.

Journalists were told to watch the puja from the terrace of Manas Bhavan, which overlooked the Babri Masjid and the kar seva site. There was strict security and we had all been given special badges. A puja was under way on a platform built during an earlier kar seva in July 1992. Top VHP leaders were there, while BJP leaders, including L. K. Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi and Vijayaraje Scindia, were in another building. According to the programme, kar sevaks were lined up state-wise and were to come and place mud from the Saryu river, which each of them was carrying.

Everything appeared to be going smoothly. Bored, we journalists went down and wandered around the puja site. The first signs of trouble came when kar sevaks who were not part of the programme strained at the barricades repeatedly. The Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) force and one burly mahant, Abhiram Pehelwan, tried to bring them under control, but they broke the barricades and swarmed over the puja site, ignoring appeals from the sadhus and mahants. RSS volunteers pushed them out and became ere the target of the ire of the kar sevaks, who soon came back when the barricades were opened for a group of swamis. This time they were armed with bricks and iron rods.

I was near the barricades around the Babri Masjid (the idol of Ram Lalla was inside) along with two other journalists. We heard a clatter and realised the masjid was being stoned. I had an adrenaline rush that journalists have whenever there is Action. My first thoughts were ‘my story wasn’t wrong’ and ‘thank God for some action’.

We ran towards the masjid and saw the first of the kar sevaks clambering over the walls. As we moved into the masjid, women CRPF constables ran out. And in a bizarre reminder of how our conditioning comes to the fore even in the most unusual of situations, Debabrat Thakur of Ananda Bazaar Patrika said, ‘Seetha, remove your shoes.’ We saw kar sevaks swarming the masjid, climbing on to it from the back and the sides. A police video camera crashed down a little away from us, a brick hit Debabrat’s hand and a CRPF constable’s shoe missed me by inches. The forces gave up the fight and we decided to leave with them, sheltered by their shields.

For the next four hours, we watched the crowds run amok, from the Sita ki Rasoi complex across the lane from the masjid complex. People were armed with pick-axes and iron rods used to dislodge heavy stones. The iron rods used in the barricades were also uprooted and used to attack the masjid structure. The crowds were frenzied and the look of ferocity mixed with glee on the faces of people sent a shiver down my spine. My journalistic elation at being at a place where history was being created was accompanied by a sense of sadness. As I later told an RSS functionary who asked me for my reaction, I felt happy as a journalist but sad as a citizen.

There was cheering each time a dome fell. We could hear Advani and Vijayaraje Scindia appealing to the kar sevaks to leave the area and not indulge in more destruction. I distinctly remember their voices booming out over the microphone–Neeche aa jaayiye (Please come down)!

There were jeers in response. But Sadhvi Rithambara’s provocative speech and Uma Bharti’s exhortations to kar sevaks to squat on the road from Faizabad so Central forces could not reach Ayodhya were met with cheers. At 4.45 pm, the third dome fell. People went wild with joy, congratulating each other.

For an hour-by-hour account of what I saw that day, please see my blog.

The demolition should not have been a surprise for someone who had spent a week in Ayodhya. Through that week beginning 1 December, I had spoken to innumerable kar sevaks–all ordinary people–who were extremely charged up. There was a frail 70-year-old woman from Maharashtra who said she had come to make rotis. Leaders who had mobilised people from their states had told us they would not be able to control their cadres if the senior leaders decided on a symbolic puja.

The late B. L. Sharma ‘Prem’, then the East Delhi MP, had been warned by his workers that they would make him wear bangles if nothing happened this time. On Saturday night, he had been nervous about meeting his workers and telling them that the kar seva was to be only symbolic. There is only a degree to which crowds primed up for a cause can be controlled.

By 7 November, overnight, the makeshift structure had come up on the hillock where the masjid once stood and the idol of Ram Lalla installed. Through that day, the hillock was swarming with saffron-clad kar sevaks, carrying bricks, cement, mud, water, clearing the debris and levelling the land, their spirits buoyed by bhajans, speeches and instructions. But by Tuesday morning, khakhi had replaced saffron and the area was out of bounds for everyone, including journalists.

Back in Delhi, some citizen’s hearing/commission was being organised. A journalist who also had been in Ayodhya asked me to testify. I agreed. But she wanted to go over what I would say. ‘Don’t you remember those people who told us they had been trained for this?’ she asked. I remembered a group that had been practising climbing on a structure, but told her I did not remember them telling us any such thing.

I soon realised that she wanted to jog my memory selectively, in a manner that would implicate specific BJP leaders and would provide evidence that the whole demolition had been pre-planned. Perhaps it was, but I was not willing to go and give that impression unless I was convinced about it.

She soon realised that I wouldn’t play ball and that I would go only by what I saw or heard, something that even some of my BJP-hating colleagues had appreciated my reports for. She said she would let me know when to appear before the commission. I was never called.

When I returned in December 2009, Ayodhya’s streets were still full of people and as noisy. But these were all local people and tourists going about their business, hawkers crying out about their wares, loud bargains being struck. People had heard about the Liberhan report, which blamed senior BJP leaders, but were disinterested in it.

Some of the people I spoke to were those I had met in 1992. My name got me embarrassed once again, as Mahant Nritya Gopal Dass, president of the Ram Janmabhoomi Nyas says (as he did in 1992), ‘Aap hi ka to kaam kar rahen hain (We are doing your work)!’ But, when he insisted the temple would get built, he didn’t sound as determined as he had 17 years earlier.

Yes, there were mahants, mutt heads and ordinary people who still said they wanted a grand temple to be built. One swami abused senior BJP leaders for betrayal in language that was unbecoming of his calling. But for the most part, people appeared to have put the events of 1992 behind them. Civic amenities and jobs were uppermost in their minds.

6 December 2014 will tell us if Ayodhya is what it was in 1992 or in 2009.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest