Politics

Six Reasons Why 2019 Didn’t Turn Out To Be 2004 For BJP’s Opponents

- Here are the reasons why 2019 elections are different from that of 2004.

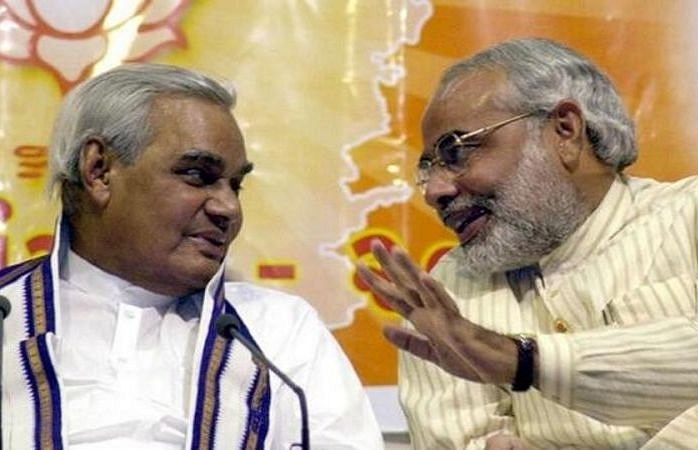

Former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee with Narendra Modi.

Soon after the exit poll findings were made public on 19 May (Sunday), there were many who were pointing to what happened in 2004 when a similar exercise showed the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government could return. But it did not happen.

Even as late as Wednesday evening, there were many trying to scare pollsters with the 2004 results vis-a-vis 2019 exit polls. But there is a big difference between these two elections.

What these sceptics failed to notice or ignore were some signs that were obvious in the lead up to the counting on Thursday.

First, do you remember Mukesh Ambani walking on the day before the results were announced in 2004 to 10 Janpath and meeting the then Congress president Sonia Gandhi? Such an incident didn’t happen now.

On Wednesday, some pointed out at Anil Ambani and the Adanis withdrawing cases against the Congress and media as signs that portend ill for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). But there are reasons for such gestures from these business houses.

No industrial house would want to antagonise any political party or media in the long term. All that these industrialists wanted to make was the point that they (politicians and media) were probably misleading the people. Now that elections are over, their concerns too are over, at least for the next couple of years.

Second is the way the 20-odd parties that are vehemently opposed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and BJP reacted to the exit polls findings. Soon after the exit poll results were made public, these leaders led by outgoing Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu got together and approached the Election Commission of India on a non-existent problem of the electronic voting machines (EVMs).

If 2019 were to be 2004, would all these parties gang up to shout from the rooftop about the EVMs being compromised? How can exit poll findings be related to the functioning of EVMs? Probably, the game was up then and there for the opposition, whose only objective was to unseat Modi.

Third, Uttar Pradesh was a problem state for the BJP in 2004. It had no clue as to how it could regain the glory achieved during the Ayodhya movement days. In 2017, the BJP swept to power, winning 325 seats and a three-fourths majority. This victory was set to be a booster in the run-up to the current Lok Sabha elections.

In Yogi Adityanath, the northern state has had a good administrator, who has single-handedly put down goondaism and brought law and order under control. Besides, the BJP was expected to gain on the back of the welfare measures — like free toilet, gas connections and aid to construct pucca houses — launched by the Modi government.

The sceptics had thought that the mahagathbandhan of Samajwadi Party (SP) and the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) would win most of the 80 Parliament seats at stake in the state, and reduce the BJP to below 20 seats.

As Congress leader Ghulam Nabi Azad said during the 1999 elections at a meeting with media at Bellary (now Ballari) “in politics one plus one will not make two”. What these sceptics ignored was that while the BSP cadre was expected to vote for the SP candidates, the vice-versa was always a million dollar question. The results have proved that the sceptics were wrong.

Fourth, the Congress got into power in states like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, while being a dominant partner in Karnataka manoeuvring to upstage the BJP in a hung assembly. Unfortunately, the Congress and other opposition parties failed to take note of one thing — Modi’s popularity.

In Rajasthan, voters had made it clear during the state elections that while they were against the then chief minister Vasundhara Raje, they would always vote for Modi in Parliament elections. Also, the Congress became a hostage of its own compulsions. It made promises of loan-waiver and employment generation during the elections to these states in November and failed to implement them properly.

In Madhya Pradesh, the return of power cuts in Kamal Nath’s regime was a bitter development for the people. In Karnataka, the H D Kumaraswamy government of Janata Dal (Secular) is living by the hour with the Chief Minister having to take permission from Congress every time he wants to implement something or make a change.

All these meant that the BJP was all set to reap the benefits of Congress non-performance in these states. The BJP went all out to net the disenchantment of the people as votes.

Fifth, the combination of Modi and BJP president Amit Shah was very methodical in its approach to the elections. In 2004, Vajpayee and L K Advani, who nursed the ambition of becoming the prime minister, didn’t gel well as Modi and Shah.

These two leaders together have shown how teamwork can do wonders for a party. At the press conference addressed by Shah on 17 May, many had wondered why Modi was present without saying anything concrete. But it was a sign of how perfect the coordination was between the party and the government.

The sixth and final difference is the people who have supported and backed the Modi government. These people have lent their support only for good governance and a corruption-free government. They underwent all the hardships, including being suspended on Twitter, expecting nothing in return. Similar support was lacking during Vajpayee’s regime.

These developments marked 2019 as a year when history wouldn’t be repeated.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest