Politics

The Karnataka 2023 Forecast

- After taking into account historic, seat-wise data and rigorous number crunching, here is a base forecast for 'Karnataka 2023'.

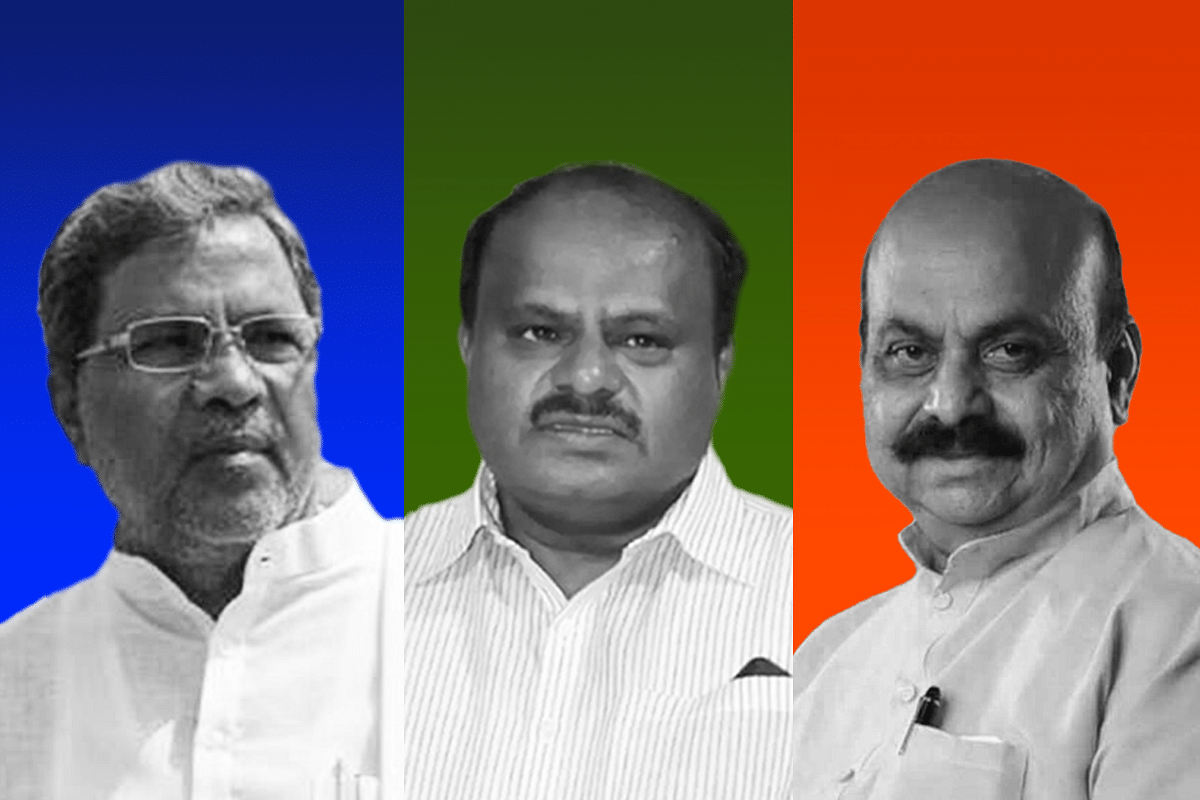

(L-R) K Siddaramaiah (Congress), H D Kumaraswamy (JD-S) and current Karnataka CM Basavraj Bommai (BJP).

The elections in Karnataka scheduled for next week are the most interesting, intense, and politically significant provincial polls since those of Uttar Pradesh in 2017. All parties in the fray have a great deal to gain, or lose, since the outcome will have an impact on both the general elections of next year, and beyond.

It is a make-or-break contest for the Congress. If they can secure the mandate, or at the very least form a coalition government if it is a hung house, then the party will be in a good position to further its case as the magnet around which a united opposition might coalesce. If they can’t, then the structural weakness of its central and provincial leadership will be shown up as wanting.

For the Janata Dal (Secular), the JD(S), this election is a last chance to retain some relevance in Kannada politics, for a little while longer, before it is swept into oblivion by the winds of change.

For the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a thumping victory would be the perfect set-up for the next round of assembly elections late in the year, and for the general elections. But if it is unable to cross the halfway mark, or increase its vote share substantially, then questions will be asked about its state leadership, its grassroots workings, and it will provide a fillip to the opposition, both in Karnataka, and at the national level.

With that in mind, Swarajya has prepared a base forecast for the Karnataka elections using a proprietary in-house predictor model.

Methodology

In the first instance, the demographic from the 2011 census, and the historical electoral data since the delimitation of 2008, were integrated onto a common platform.

Next, a rigorous analysis was carried out for every assembly seat, and then for the six regions of the state, since voting patterns and demographics in Karnataka vary widely. These analyses included vote share tranche analysis, margin tranche analysis, vote swing analysis, triangularity, and many more.

This number crunching was then integrated with the results of by-elections since 2018, defections, ground inputs, and qualitative assessments like candidate selection and campaign strategy, to generate predictor curves for the BJP, the Congress, and the JD(S).

Finally, forecasts were run on the model for the BJP and the Congress, but not for the JD(S), while continuously checking for errors, mismatches and contradictions. This is because, as will be explained in detail below, the JD(S) is mainly concentrated in just one region of Karnataka – Old Mysore State in the south.

Assumptions

A number of assumptions were made aforehand, to set frames of reference for the model, and also because hardly any credible opinion poll surveys were released until almost the end of the campaign. These include:

The JD(S) is expected to get squeezed in northern Karnataka, with the bulk of its identity vote shifting to the Congress. That makes the JD(S)’s fortunes difficult to predict.

Both the Congress and the BJP are expected to eat into the JD(S) stronghold of southern Karnataka, with more Vokkaligas voting for the BJP than before.

Bipolarity will increase, with a greater number of the contests being between the Congress and the BJP. This will increase the vote share required to win seats, lower margins, and heighten unpredictability.

The ‘Others’ vote share, which has been declining steadily since 2008, is expected to decline further slightly. But the probability of it going below 6 per cent is low.

Consequently, the predictor model curves for the BJP and the Congress were set as primary ones, and that of the JD(S) as a secondary one (meaning, essentially, that the performance of the JD(S) would largely be a function of how the other two parties perform).

The Dalit vote has finally started gravitating towards the BJP.

The BJP could do better in reserved tribal seats.

The tremendous surge the BJP enjoyed in the 2019 general elections, when it swept the state, will be mimicked to a material extent in 2023.

A consolidation of the identity votes in opposition ranks will cause a supra-caste counter-consolidation in favour of the BJP.

The BJP will be the single largest party in terms of seats, and, for the first time, by vote share as well.

Surveys which say that the JD(S) vote share will go up from the 18 per cent it got in 2018, or that the BJP’s vote share will reduce from 36 per cent, deserve to be treated with abundant caution.

The credibility of surveys which don’t disclose vote shares is treated as suspect.

Some unquantifiable unknowns exist. The most important uncertainty is the extent to which the JD(S) may crumble. Another is the extent to which the BJP will benefit from its central welfare schemes implemented through a ‘double-engine sarkar’; the ‘labharti’ vote. A third is the impact of infighting within the Congress. A fourth is the Modi factor, which is very much in play in Karnataka.

Running the model and determining margins of error

By late April 2023, Swarajya’s assessment was that the vote share distribution would most probably be: BJP 42 per cent, Congress 40 per cent, JD(S) 12 per cent, and ‘Others’ 6 per cent.

Plugging the BJP and Congress numbers into the model returned the following results:

And this is how the outputs plotted up on the chart:

We see that the outputs of both the BJP and the Congress fit very well on the predictor curves (colour coding: orange-BJP, blue-Congress, green-JD(S)).

But, the JD(S) point falls well off the curve. This is a function of the party’s very high sensitivity to multiple factors, especially vote swings (in 2018, a sixth of its wins were low scoring triangular contests). However, rather than treating this curve-data point mismatch as an error, what we must understand is that this incongruity is, in fact, an extremely useful tool for quantifying the margins of error for predictions on how the Congress and BJP might actually perform.

The JD(S) point sits 4 per cent and 12 seats off its curve. That returns a vote share margin of error of plus-or-minus 2 per cent, and a margin of error for seats won of plus-or-minus 6 seats, for the other two parties.

As absurd as it may sound, the JD(S) data point of a decent forecast should either not fall on the JD(S) curve, or, the pollster should discount the result, attribute the balance vote share to it after subtracting that of the BJP, Congress, and ‘Others’, and read the seat count off the curve. In our case, this exercise suggests that the JD(S) would get under 15 per cent of the vote share, and win less than 20 seats.

It is a good lesson for pollsters since it shows how tough it is to make predictions for the 2023 Karnataka assembly elections. This is quite similar to the assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh in 2022, where analysts struggled in vain to successfully quantify the disintegration of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP).

Thus, the prediction range for our base forecast has high confidence levels for the two larger parties: 107-119 seats for the BJP with 40-44 per cent vote share, and 81-93 seats for the Congress with 38-42 per cent vote share.

The point to be noted here is that the number of seats won by the three parties could experience fluctuations with relatively minor changes in vote shares because of the numerous factors at play (covered in the analysis methodology and assumptions).

Next, the forecast was compared with four surveys till the end of April – two by ABP C-Voter in late-March and late-April, one by Spick in early-April, and one by Eedina in late-April. This is how their results compare with Swarajya:

Both the ABP polls are non-representative of prevailing electoral dynamics and ground realities for reasons elaborated here.

The Spick forecast of early April appears fair. Its lower BJP vote share, and a higher seat count for the Congress, may be reflective of ground conditions before candidates were finalized, and the campaign picked up.

The less said about the Eedina survey presented by Yogendra Yadav, the better.

In the third step, the Swarajya forecast was compared to a major survey by Zee-Matrize which was released in the first week of May.

We see that the Zee-Matrize survey is broadly within range, with their JD(S) forecast reassuringly not falling on the party’s green predictor curve. Once again, readers may note that the more a poll gets the BJP and Congress numbers right, the more it will tend to get the JD(S) numbers wrong.

Also, it must be reiterated in closing that the Swarajya prediction is a base forecast. Consequently, it will be interesting to see what the actual numbers turn out to be, if the BJP goes past the 42 per cent vote share mark.

Thus, to summarize, this is how the Swarajya forecast stacks up in comparison to a number of surveys released between late March and early May 2023

Now, a few days of campaigning still remain, but as things stand, the higher probability is that the BJP will reach the majority mark in Karnataka.

If it does so, then it will be fulsome validation of a central thesis – that these assembly elections constitute a fresh benchmark in Karnataka’s electoral history because they mimicked the results of the 2019 general elections to a material extent, by a triggering of the civilizational vote.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest