Politics

Uttarakhand 2022: There’s A First Time For Everything

- There is a high probability that the BJP would buck the odds and return to power in Uttarakhand for a second term. After all, there’s a first time for everything.

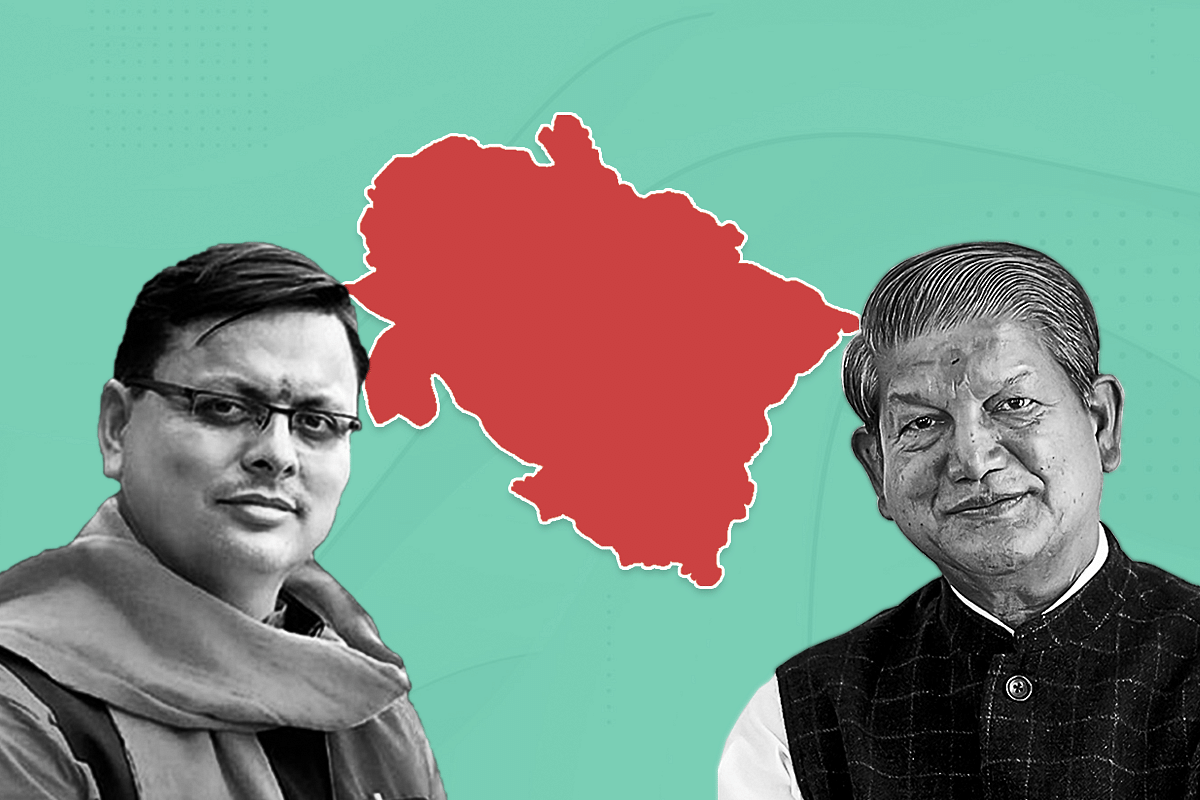

Pushkar Singh Dhami of BJP and Harish Rawat of Congress.

The first thing analysts point out about Uttarakhand is that no party has won a second successive term since elections were first conducted in the state in 2002. The second thing they point out is that both the main parties there, the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), have suffered from frequent leadership crises.

As a result, incumbent Chief Minister, Pushkar Singh Dhami of the BJP, is not just the tenth man to hold that post in the past two decades, but the third in the past year alone.

Using that yardstick, a number of political pundits in mainstream media have been quick to conclude that the BJP will be contesting next month’s assembly elections in Uttarakhand with two handicaps weighing them down — anti-incumbency and internal strife.

But what do the numbers say?

In 2012, the Congress pipped the BJP as the single largest party in a hung house, by a solitary seat and 0.7 per cent of the popular vote. It was a turbulent period, seeing two chief ministers, two very brief periods of President’s rule, sulks, maladministration of a terrible natural disaster, and ‘secular’ cluelessness in policy-making.

It was no surprise then, that the BJP swept the 2017 elections in style, winning 57 of the 70 seats, and a remarkable 46 per cent of the vote (up 13 per cent from 2012). The Congress, interestingly, held on to its vote base, but the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) lost almost half its votes to the BJP, and the sizeable ‘Others’ component, over a third.

The BJP improved upon that victory with an even more remarkable performance in the 2019 general elections, winning an astounding 65 segments with 62 per cent of the vote.

But 2019 was an outlier swell wave caused by Narendra Modi and nationalism; it is not expected to manifest itself in 2022. Therefore, our benchmark for electoral analyses will be the 2017 elections.

This is how the results were distributed in 2012:

In 2017, the BJP expanded comprehensively within the state:

And in 2019, the saffron sweep was a near total:

However, we see that this majestic saffron swathe is marred by a few blue splotches, in a solitary part of the state — Hardwar. Hark back to the 2012 map and we see that this is the same district where the BSP registered its only three victories.

The reason is depressing; these results are proof that Devbhoomi is yet to fully rid itself of rank identity politics. Linking these repeated similar results with surveys suggesting an advent of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) into Uttarakhand in the forthcoming elections, it is important that we study the state’s demographics, to understand how these new entrants might stir the infernal identity pot for their electoral benefit.

This is a map of Hindu demographics by district across the state:

Note how most districts are uniformly, and overwhelmingly, Hindu, save two — Hardwar and Udham Singh Nagar.

Step two, look at the Muslim demographics of Uttarakhand:

Note how this community is so heavily concentrated in a few districts — particularly in Hardwar, where they constitute 34 per cent of the district’s population. Pound to a penny, these areas will constitute the AAP’s primary targets in 2022.

Next, look at the state’s Scheduled Caste demographics. No prize for stating the repugnantly obvious, but this segment was the BSP’s primary target for decades, which they pursued assiduously, albeit with only limited success. Readers may bet their last bitcoin that the AAP will seek to do a BSP in this segment as well.

We see that the distribution is roughly even, with a slightly higher concentration in Bageshwar, and relatively less in Dehradun and Udham Singh Nagar.

In step 4, the demographic data of Muslims and Scheduled Castes were combined, to try and define the arena within which practitioners of secularism might ply their art:

It is plainly obvious that secularism can (and does) directly influence electoral outcomes in Hardwar, Nainital and Udham Singh Nagar districts.

Now, bearing in mind that the BJP is congenitally hopeless at ‘playing’ identity politics (it is their principal, eternal failing), how does all of the above fit into electoral outcomes in 2022?

One major factor in Uttarakhand is the ‘Others’ — a host of independents, rebels and small parties which have traditionally commanded a significant chunk of the vote. In 2017, they got more than 10 per cent in 31 seats — almost half. Of these, the BJP won 24, the Congress five, and independents, two.

In 12 seats, they command over 30 per cent of the vote. Of these, the BJP won eight, the only Congress two, and independents, two.

More pertinently, the ‘Others’ vote, plus what used to be the old BSP vote, outnumbers the Congress in 19 seats, while it does so over the BJP only in 10. And even in these 10, independents came first in two, second in three, the BJP won five, and the Congress only three.

The inference is that the Congress is inherently more susceptible to losing in a fractured electorate than the BJP, because it consistently polls less than the ‘Others’-plus-BSP than the BJP does. The AAP will be eyeing this truth gleefully, because this is also what makes it tougher for the Congress to go past the BJP, unless there is a substantial, direct, vote shift from the BJP to the Congress.

This observation is substantiated by an analysis of 2017 win margins. The Congress’s average win margin in 2017 was 3.1 per cent (discounting Ranikhet, where it registered a ‘record’ 12 per cent margin). On the other hand, the BJP’s average win margin was 14.4 per cent; it got less than 5 per cent only in 10 seats, of the 57 it won, and over 10 per cent in 40 seats. This means that the BJP will have to suffer a negative vote swing of over 10 per cent in at least 20 seats, if the mandate is to shift.

That Congress fallibility becomes more vividly apparent when we plot 2017 wins on a win margins map:

Note how the bulk of the BJP’s wins in 2017 were with solid margins, while those of the Congress were more marginal. The implication is fundamental: the BJP needs to lose more votes, to lose a seat, than the Congress does.

So, what do the surveys say? Will the BJP suffer enough of a negative vote swing to gift the mandate to the Congress, or will it be a hung house, or what?

The answers of the two most recent, comprehensive, surveys say different things: both predict that the BJP will lose some votes, but will still reach a simple majority. The results of the Times-Now and Republic polls are given in a table below:

The Times Now poll of 10 January 2022 says that both the BJP and the Congress will lose the same amount of votes to the AAP (along with the bulk of the old BSP base, and a fraction of the ‘Others’). But since there would be no vote transfer from the BJP to the Congress, a lower index of opposition unity means that it would be a repeat BJP sweep.

The Republic poll of 17 January 2022 is slightly more complicated. It too shows a drain of votes from the BJP, the BSP and ‘Others’, mainly to the AAP, but it also shows the Congress gaining 4 per cent, to come nearly neck-and-neck with the BJP. And yet, the Republic polls still gives the BJP a renewed mandate.

For that to work, especially since the vote share differential between the Congress and the BJP narrows to a wafer, we have to read it as BJP votes going to the AAP and not to the Congress (something which Arnab Goswami pointed out repeatedly when the survey results were being presented).

Another aspect is that, perhaps, dissent within the BJP is being cancelled out by dissent within the Congress, allowing the new entrant to benefit.

In effect, we have two major surveys both saying the same two things in different words: one, that votes would shift from the BJP to the AAP, but not to the Congress; and, two, that this would result in the BJP being returned for a new five-year term.

Integrating the surveys’ results with in-house number crunching, this writer believes that the BJP’s present, base vote share in Uttarakhand would be in the 42-44 per cent range.

Going by that, in conclusion, the higher probability is that the BJP would buck the odds and be returned for a second term. After all, there’s a first time for everything.

All data from Election Commission of India and Census 2011 websites.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest