Politics

West Bengal’s Bid To Build Schools Through PPP Will Face Purchasing Power Hurdle

- Moving to PPP mode will help the Banerjee government to steer clear of many problems, but successful implementation of the scheme will not be easy in the political-economic reality of West Bengal.

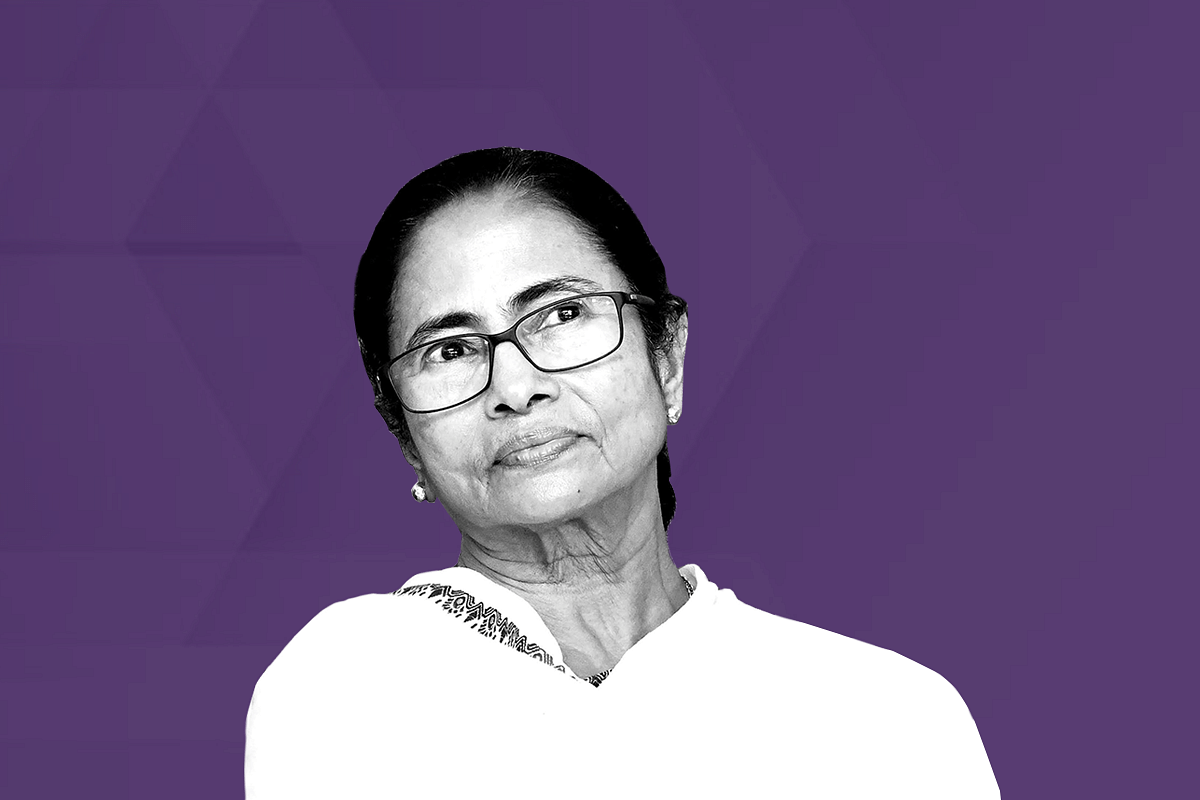

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee.

The draft policy for public private partnership (PPP) in school education is a welcome move by the West Bengal government. The government will offer unused school infrastructure. The private sector will take all operational decisions — including medium, board etc — and will ensure quality education, of course for a fee.

While the precarious financial status of the state may be the prime inspiration behind the move, the initiative is timely in view of the distinctly low total fertility rate or TFR (1.6) in the state that demands consolidation and greater emphasis on quality. Successful implementation of the scheme, however, will not be easy in the political-economic reality of West Bengal.

Low TFR

Total fertility rate (TFR) is a measure of the average number of children that a woman gives birth to, during her lifetime. At a 2.1 fertility rate, the population remains stagnant in the long term.

According to the 2011 Census, West Bengal (and Tamil Nadu) had a TFR of 1.7, the lowest among major states. Urban fertility was as low as 1.3 and rural 1.7. The National Family Health Survey pegs state TFR at 1.6 in 2019-20. Urban TFR is 1.4 and rural 1.7.

The trend is most prominent in Kolkata. Researchers point out that the city’s fertility had been at replacement level at least 40 years ago and the current TFR is somewhere near 1.

Add exodus of the working-age population, for better employment opportunities, and Kolkata’s population declined in Census 2011. The plush Salt Lake satellite township became a colony of the aged. The average age in any housing society is no less than 50.

Reducing fertility and aspiration for quality education already led to the closure of many government schools, particularly in urban areas. Ironically a once reputed government-run school in Durgapur steel city was recently converted into an old-age home. The makeover was possible as land and infrastructure were owned by a public sector undertaking (PSU).

According to a media report, of the 980 government-aided junior high schools (classes V-VIII) in West Bengal most were running at one-fifth of student capacity before the Covid-19 pandemic and 64 had no students. Stories keep coming in bits and pieces about the lack of students in government schools.

National Trend

That government schools are failing to attract adequate students is a nationwide phenomenon. TFR is falling across the country and is now just below the replacement rate. With smaller families and rising income, parents are preferring private schools for better education.

According to India’s Ministry of Education, in 2012-13, 57.3 per cent of 26.22 crore students enrolled (pre-primary to Class-XII) in government schools, 11 per cent in government aided, 28.1 per cent in private and 3.6 per cent in others (charitable trusts etc).

In 2019-20, the total enrolments increased by only 0.9 per cent to 26.45 crore but the share of private sector reached 37.1 per cent. The share of government schools was down to 49.5 per cent.

Geeta Gandhi Kingdon, professor of education and international development at the Institute of Education, London, pointed out that student enrolment in government schools in 20 major states fell by 13 million between 2010-11 and 2015-16. During the period, private schools acquired 17.5 million new students.

Kingdon’s findings, which were reported by India Spend, points out that 80 per cent of India’s education budget is used on teachers’ salaries, training and learning material. When compared against per-capita gross domestic product (GDP), India’s government school teachers earn in multiples of many rich countries and four times of China.

By this yardstick, teachers in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are not only highest paid in India but earn salaries that are a few times more than the average in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. It is anyone’s guess how much salaries translated into the quality of government school education in these states mushroomed with cheap private schools.

The other side of the coin is states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu which don't spend as much on teacher-salary (compared against per-capita GDP and SDP) have better performing government schools and elite private schools.

Overall, the high salaries of government teachers have questionable outcomes. “The performance of Indian teachers judged in terms of their students’ learning levels, has been poor in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test in 2009, with India ranking 73rd and China ranking 2nd, among 74 countries,” reports IndiaSpend.

West Bengal

Theories apart, the political-economic reality of India is: people have low faith in government services but high admiration for government jobs which come with the perceived assurance of low accountability.

Add to this abundance of paper degrees and you see lakhs, including PhD holders, queueing up for the most insignificant government positions. Due to the relatively high volume of recruitment and associated social prestige, demand for teaching jobs is extraordinarily high.

The phenomenon is most prominent in states which suffer from low levels of economic development, entrepreneurship etc. West Bengal is one of them. Low employment opportunities in the state and dominant fancy for white-collar jobs made the situation worse. Traffic goes haywire for teacher eligibility tests (TET) as lakhs come out on the streets.

A disproportionately high demand-supply gap gives rise to corruption. Naturally, controversy is common in government recruitments in West Bengal. A former Trinamool MLA allegedly ensured teaching jobs to one-and-a-half dozen of his family members. He later joined Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Moving to PPP mode will help the Mamata Banerjee government to steer clear of many problems. However, it is questionable if the prevailing political economy will allow it. Should the local politics allow the efficient running of such schools?

That’s just the beginning of the problem. Banerjee government went whole hogged on teacher recruitment and opening new schools in her first term (2011-2016). To bring sanity to school education, the state should now take a U-turn and close many schools. Will it be politically possible?

Low Purchasing Power

The biggest problem lies elsewhere. Kerala and Tamil Nadu are widely appreciated for the quality of government school education. However, the share of the private sector in these two stands at 30 per cent and 46 per cent respectively.

In comparison, the share of private schools in total enrolment is 13.8 per cent in West Bengal, comparable to Bihar’s 12 per cent. Assuming parental aspirations remain the same countrywide, the difference apparently lies in purchasing power.

Ideally, TFR and income are inversely proportional. Fewer children are born in rich countries. Tamil Nadu and Kerala buck this trend. But West Bengal is an aberration of this theory.

Of the 33 states and union territories, West Bengal is ranked 20th (just above Tripura) in terms of per-capita net state domestic product (nominal). Tamil Nadu sixth, Kerala ninth and Bihar last.

Tamil Nadu became a top industrialised state of the country in 30 years of reform. Kerala is a top foreign remittance earning state. It also has a thriving high-value hospitality sector. West Bengal is a graveyard of industries and failed to create a high-value service sector.

Add to this high inequality between Kolkata and the rest of the state.

This was also reflected in the rural-urban TFR gap in the past. According to the 2011 Census, The TFR in West Bengal was highly unequal as against Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The error is somewhat corrected in NFHS 2019-20. Benefits will take time to accrue.

To cut the long story short, West Bengal remained an aberration in the national trend of the rising share of private schools due to low purchasing power. Bihar also suffers from the same problem and 70-80 per cent of private schools there charge Rs 500 or less (IndiaSpend).

Quality education comes at a cost. The average payout per student in any top public school in Kolkata is in the range of Rs 10,000 per month. Too much compromise with cost will lead to the recruitment of substandard teachers, which is an antithesis of the stated goals of PPP schools.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest