Politics

What Is BJP Afraid Of In OBC Census?

- The Union government’s likely fears about a new OBC census revolve around a few important issues.

- Here are some of them.

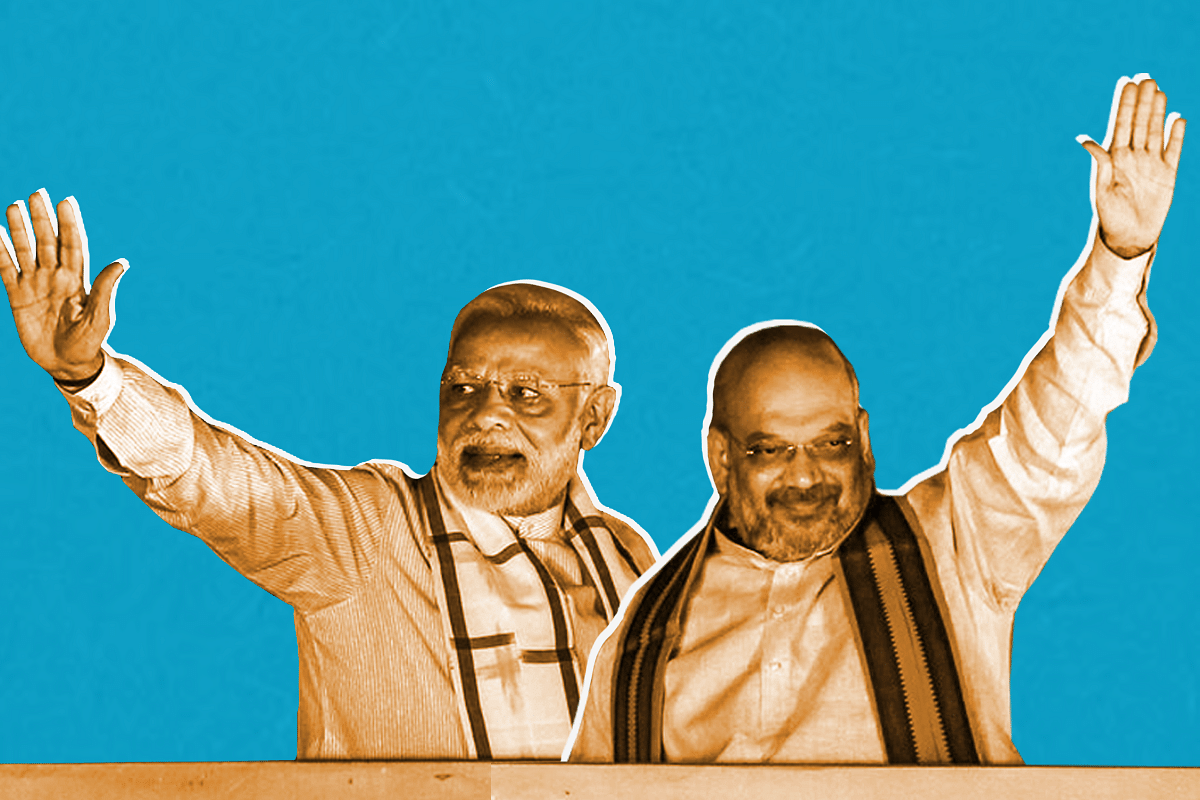

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah.

The chorus for a national census of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) has not just gotten louder, but also shriller, with Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) allies like Nitish Kumar demanding it. The Narendra Modi government, after legislating a constitutional amendment to allow states to determine who is backward, thought it had handled the political timebomb well. But apparently the opposition has no intention of letting go of this issue.

The question: is a caste census something that the BJP needs to be scared of? If yes, why? If no, why?

The quick answer: in the short-term, it could be a problem, but not in the longer term. That is, if the BJP intends to build a durable coalition of castes as part of its Hindutva project, which currently it does not plead guilty to.

Let’s first understand why an OBC census is political dynamite and why the opposition wants it to land on the Centre’s desk rather than its own. After all, the whole point of passing the 127th Constitution Amendment Bill was to give states the right to decide who is an OBC. They can do so even without the Modi government agreeing to do so. They can create their own lists, do their own census of OBCs.

But here's the point: caste censuses have the potential to upset calculations even for those demanding it. Hence the decision to lob the grenade on Modi’s lap. All community-based censuses impact electoral politics, with existing caste coalitions giving way to new ones as the numbers point in a different direction after each census.

Karnataka conducted an OBC census before the last Congress Chief Minister, Siddaramaiah, bowed out in 2018. But he did not release the results because it would have upset the dominant and powerful Lingayats and Vokkaligas, who were shown to have lower numbers than expected. Both of them were expected to reject the census if unveiled.

According to a report in The Indian Express, “A leaked version of the (Karnataka) census report had indicated that dominant castes like the Lingayats constitute only 9.8 percent of the population (instead of a general estimate of 17 percent) and Vokkaligas 8.2 percent (instead of 15 percent) in the six-crore population of the state.”

This number, if made official, would have enabled completely new electoral combinations to emerge, throwing either the Lingayats or the Vokkaligas, or both, into positions where they could be ignored in political calculations. The surest way to anger the Lingayat and Vokkaliga communities is to tell them they are too small to matter. This is why even state politicians fear to open the Pandora’s box of caste census after actually ordering it.

The Union government’s likely fears about a national OBC census revolve around a few important issues surrounding it.

One, such a census, if it unveils much higher OBC numbers than currently assumed, would automatically lead to demands for higher OBC quotas for jobs and university seats in central-run institutions. At some point, pressure will mount to breach the Supreme Court-mandated 50 per cent limit on reservations. It could snowball into a demand for constitutional amendments to ensure the same. The moving target will be 69-75 per cent reservations, with both SCs/STs and OBCs gaining.

Two, there is a good chance that the upper castes, widely assumed to be upto 15 per cent of the population, may be smaller in numbers now. This core constituency of the BJP would be upset if its concerns are not seen as important in future. There is a reasonable basis to assume that the upper castes are smaller in numbers now than they were before because their total fertility rates (TFRs) may have fallen faster than that of OBCs, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (SCs/STs) and Muslims. TFRs tend to be lower for the better off.

It is worth noting that the population of SCs/STs, which is counted with every census unlike that of OBCs, increased from 14.6 per cent for SCs and 6.9 per cent for STs in 1971 to 16.2 per cent and 8.2 per cent respectively in 2001. This led to an increase in Lok Sabha seats reserved for the SCs from 79 to 84, and for STs from 41 to 47.

If we assume similar increases in OBC populations, while there will be no immediate increase in reserved Parliament seats, there will be demands for higher representation for them among political parties and also for increases in job and education quotas.

Three, the real nightmare will come with the headcount, which is hardly as simple as it sounds. Already, state OBC lists differ from that of the Centre, and some states even allow Muslims and Christians to categorise themselves as OBCs without in any way asking their religious heads to formally acknowledge that they have done little to eradicate casteism within their flocks. Their claims of being superior to caste-bound Hindu society will then sound hollow.

There is also no reason why some groups, classified as OBCs by states, will not demand the same status at the Centre, which will entitle them to jobs and quotas in central government undertakings and institutions.

Thus, while the headcount and its measurement will itself give rise to tensions, after it is completed, there will be more demands for inclusions and exclusions in some or all the states. At some point, one can also see Muslims and Christians demanding reservations in central services through the expansion in OBC quotas.

One can also visualise tensions among OBC castes that lose out and those that gain. For example, what if the Yadavs of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar (both dominant in their respective states) are shown to be growing slower than other segments of OBCs? What if the Kurmi population rises in relative terms in both states?

So, an OBC census is not going to solve anything, and politics over its content and extent will continue till the cows come home.

Let's now come back to the question we asked earlier: does the BJP have to fear such a census?

In the short run, certainly. It will face issues if OBCs are shown to be larger in number than we assume now. It will also cause heartburn among the upper castes which have voted solidly for the BJP in many states.

But, in the long run, the BJP may well benefit from an expansion of the OBC numbers and they are given more quota benefits, for this is the bedrock on which the foundations of Hindutva can be built. The numbers for a viable Hindu coalition exist among OBCs, not the upper castes.

It is worth recalling that the BJP’s base expanded only after the Mandal reservations took root and the party did its own bit of social engineering.

Mandir and masjid were seen to be political opposites, but after Mandal, the OBCs were happy to see their status lifted where they could be part of the larger Hindu mainstream. Without Mandalisation, the BJP’s OBC base would have been much smaller. The rise of an OBC person as Prime Minister would have been less probable.

A big truth: Hinduism exists more in its jatis and sub-castes, and when these groups are empowered, they get mainstreamed in terms of Hindu identity. The Hindutva project, even if it costs the BJP in the short term, will benefit it in the longer-term.

The only question that remains is this: how committed is the BJP to the Hindutva project? The jury is out on that one.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest