Politics

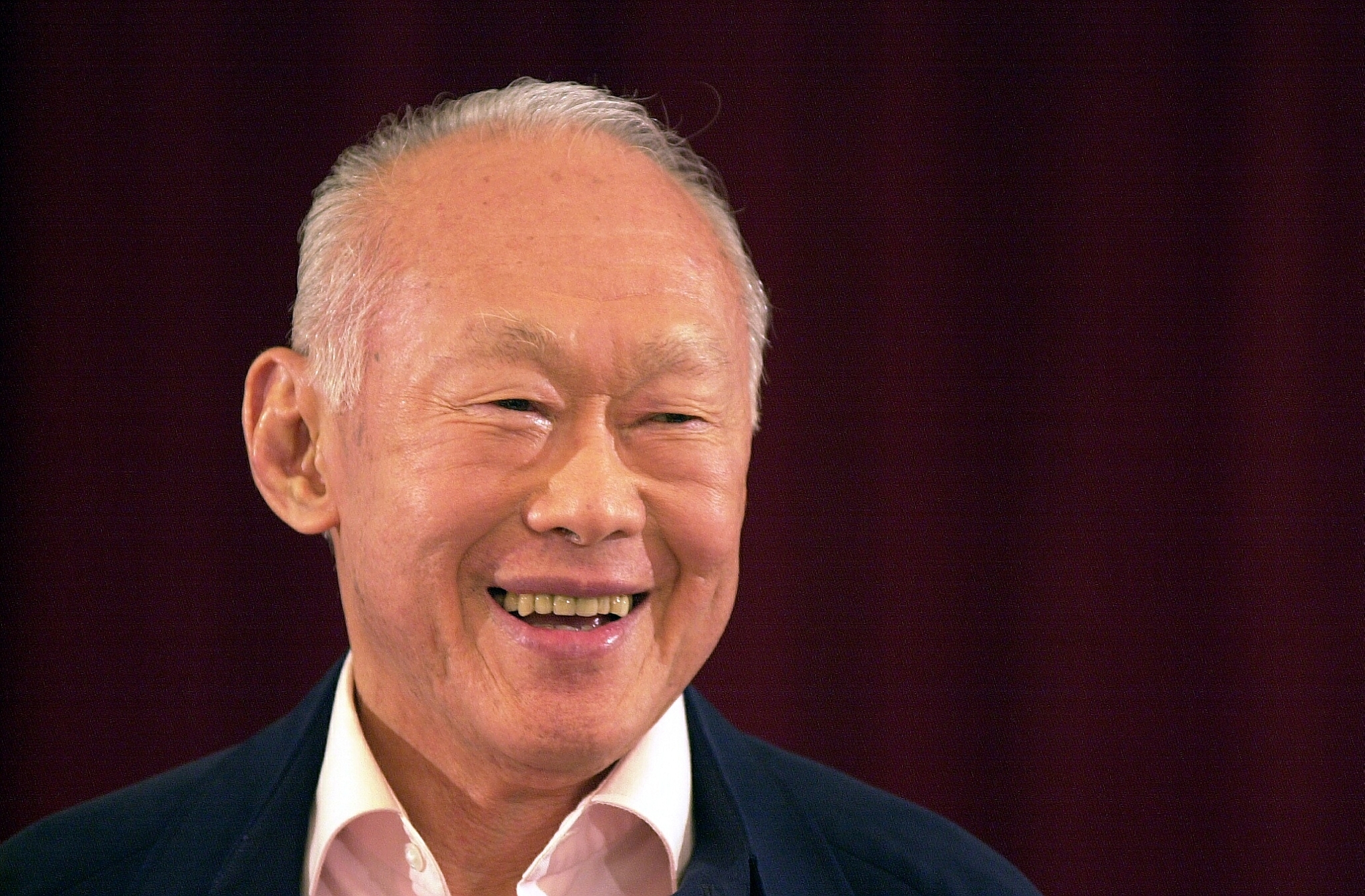

Why Lee Kuan Yew Believed Democracy Was A Drag

The creator of modern Singapore, who passed away on March 23, thought that India’s political system has left it “a nation of unfulfilled greatness”.

Is democracy a spoiler for India? Is it a drag that prevents us from achieving great power status? According to one of the greatest strategists of the 20th century, that would be more or less correct. In the words of Lee Kuan Yew, the late Singapore strongman, “The exuberance of democracy leads to undisciplined and disorderly conditions which are inimical to development.”

In Lee’s view, “Democratic procedures have no intrinsic value. What matters is good government.” According to the Singapore strongman, the government’s primary duty is to create a “stable and orderly society” where “people are well cared for, their food, housing, employment, health”.

“Democracy is one way of getting the job done, but if non-electoral procedures are more conducive to the attainment of valued ends, then I’m against democracy. Nothing is morally at stake in the choice of procedures.”

Lee Kuan Yew: The Grand Master’s Insights on China, the United States, and the World by Graham Allison, Robert Blackwill and Ali Wyne, includes a chapter on India. In this book, Lee says in his no-nonsense style: “India has wasted decades in state planning and controls that have bogged it down in bureaucracy and corruption. A decentralised system would have allowed more centres like Bangalore and Bombay to grow and prosper….India is a nation of unfulfilled greatness. Its potential has lain fallow, underused.”

Lee’s believes the culprit is uncontrolled democracy. “There are limitations in India’s constitutional system and the political system that prevent it from going at high speed. Whatever the political leadership may want to do, it must go through a very complex system at the centre, and then even a more complex system in the various states….Indians will go at a tempo which is decided by their constitution, by their ethnic mix, by their voting patterns, and the resulting coalition governments, which makes for very difficult decision-making.

“Furthermore, populist democracy makes Indian policies less consistent, with regular changes in ruling parties.”

Nation building: no easy task.

During a rally in 1980, Lee described what it took to transform a small, dirty colonial trading post into one of the wealthiest nations in the world: “Whoever governs Singapore must have that iron in him, or give it up! This is not a game of cards! This is your life and mine! I spent a whole life-time building this, and as long as I am in charge, nobody is going to knock it down.”

Lee walked his talk. Under him, Singapore became a de facto one-party state. He disallowed dissent, curbed free speech, introduced corporal punishment, and even banned chewing gum. Was he a tyrant? Benevolent dictator would be a better description. Indeed, Singaporeans loved him for raising their living standards and, more importantly, their prestige.

Lee served in office from 1959 to 1990, during which time he led his country through a period of remarkable economic growth and diversification. When he took over as Prime Minister, Singapore’s annual per capital income was $400; today it is estimated at $56,000.

The road not taken

If Singapore had taken the democratic route, would it have been as chaotic as India? Would it have been less prosperous? For the answers let’s turn to Russia and how it experimented with unbridled democracy and then later with strong central rule under President Vladimir Putin.

When democracy arrived in Russia after the collapse of communism in 1991, it was pretty much free for all. The country was under the grip of criminal syndicates and sundry opportunists. The economy, remote controlled by the IMF, was in free fall, without the bottom in sight.

And yet in the western view, “God was in his heaven and everything was right with the world.” The suffering of the Russian people didn’t matter to them. Rather, the pictures of once proud pensioners now reduced to trading their World War II medals for a loaf of bread were gleefully published by TIME, Newsweek, and The Economist.

Into this mess, Putin walked in. His entry was dramatic – the Russian stock market jumped 17 per cent the day he got the job in 1999.

During Putin’s first stint in power (from 1999-2008), the Russian economy recorded an average growth of 7 per cent annually. During this period, industry grew 75 per cent, while real incomes more than doubled. The monthly salary of the man in the street went from $80 to almost $600. The IMF, which worked overtime to destroy Russia’s state-owned corporations and banks, admits that from 2000 to 2006, the Russian middle class grew from 8 million to 55 million. The number of families living below the poverty line decreased from 30 per cent in 2000 to 14 per cent in 2008.

How did Putin achieve that? First up, he rejected the notion that western democracy and values are universal. This is precisely what Lee had done in Singapore. As the Singapore Prime Minister was fond of saying, “I do not believe you can impose on other countries standards which are alien and totally disconnected with their past.” In his view, “to ask China to become a democracy, when in its 5,000 years of recorded history it never counted heads” was completely unreasonable.

The West treats democracy as religion – so sacred that it will bomb countries into the stone age in order to sow the seeds of democracy in those places. That is what George W. Bush claimed the Americans were doing in Iraq. Now, the Americans and their NATO friends claim they are introducing democracy in Libya. Both attempts have been spectacular failures.

Imperfect system

In a democratic form of government the party or candidate that gets the most votes is the winner. Such a system may seem fair but in reality can create unfortunate outcomes. For instance, a large number of candidates can divide votes so that a totally unpopular candidate can squirm his way to power. This has happened most starkly in India where the Congress party ruled India for over five decades despite not getting the majority of the votes. In the US, western democracy could not prevent the theft of the 2000 Presidential elections where Al Gore got more votes than George W. Bush and still lost. Bush stepped into the White House and took the US into the senseless war against Iraq, in 2003.

Lee spoke against such imperfect election tools during an interview in 1999:

“My view is that people’s preferences matter, but I don’t define the people’s preferences as merely the views of existing majorities. ‘The people’, as I see it, includes future generations, and governments have a special responsibility to resist popular pressure for tax breaks and welfare measures that undermine the prospects of future generations. So perhaps we should define democracy as a government chosen by the people, including contemporary and future generations.”

In contrast to Lee’s strong sense of nationalism, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was completely delusional. Instead of raising living standards, Nehru spent his time and energy on the chimera of world peace. His detractors deride him as the “breaker of modern India”. Unlike Lee, Nehru lapped up what his former colonial masters dished out to him. He imposed western democracy on a poor and divided country, causing chaos that slowed economic growth and caused numerous caste and religious conflicts.

A leader who protects his country’s interests is not necessarily a tyrant. Gen Augusto Pinochet, a western stooge who killed thousands of Chileans, was a tyrant. Lee and Putin, on the other hand are nation builders. Indeed, because of the dramatic economic growth of Russia, China, Singapore and other South East Asian countries, authoritarian prosperity rather than democracy is now a viable governing option for developing countries. It is yet another example of the rejection of western ideas by the emerging world.

Around 2300 years ago, Chanakya, the original master of statecraft and policy and the mentor of the greatest empire in Indian history, wrote in the Arthashastra: “The foremost duty of a ruler is to keep his people happy and contented. The people are his biggest asset as well as the source of peril. They will not support a weak administration.”

It’s ironic that while a man of Chinese ethnicity internalised Chanakyan strategy, Indians have paid lip service to it.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest