Science

Dr Thanu Padmanabhan (1957-2021): In Remembrance

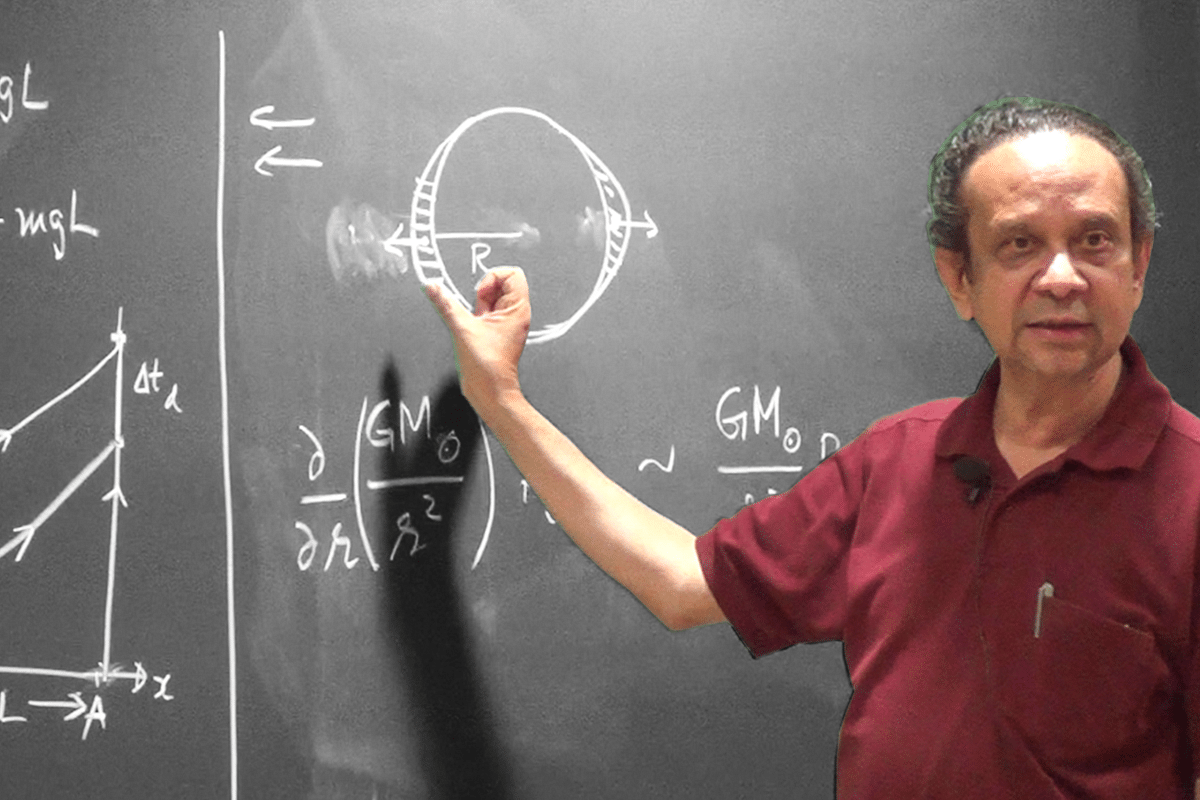

- Padma Shri recipient, theoretical physicist and cosmologist, Dr Thanu Padmanabhan passed away in Pune on Friday, 17 September.

- Here is a recollection of the scholar's life and works and his lasting contributions to science.

Prof Thanu Padmanabhan

A dedication in a book can sometimes bring out the innermost yearnings of the author. The book had an interesting title – After the first three minutes – the story of our universe, Cambridge University Press, 1998. Coming two decades and a year after the perennial classic The First Three Minutes, written by physicist Steven Weinberg, this book about the cosmic after-story after the first three minutes had been written by an Indian physicist – Thanu Padmanabhan.

Padmanabhan was with the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCCAA) at Pune - one of those institutions that make an Indian proud.

One problem with popular science books is that they make the science look so elegant, beautiful and more importantly simple, that the non-specialist reader becomes vulnerable to the delusion that science is all about exotic speculation. This book was different, in the sense that it combines the best of two worlds – lucid narration with a text-book style explanation. And for an undergraduate student of physics, this book can be the gateway to the challenging mysteries in cosmology.

In the last chapter on open questions, Dr. Padmanabhan brought out the question of aesthetics. Physicists building cosmological models also look for aesthetics in their models and not without reason:

But post-1992, models have been ‘quite unpleasing’ on the aesthetic front. Even the conventional cosmological model which Padmanabhan adheres to in the book, ‘predicts a singularity at some finite time in the past’, which ‘is probably the most unaesthetic feature any theory can have!’ But it has explanatory power in terms of observed phenomenon like for example, the microwave background radiation.

One is reminded here, of the argument of Sabine Hossenfelder, as to how aesthetics could actually lead physicists away from truth and Michio Kaku’s partial acceptance and rejection of this stand. But that would be again two decades later.

He also co-authored with his wife Vasanti Padmanabhan, also an astro-physicist, a book on the history of science: The Dawn of Science: Glimpses from History for the Curious Mind (Springer, 2019).

This book provides an excellent walk through the history of science in a non-Eurocentric way. It also highlights Indian achievements. There are no exaggerations and the book makes the reader realise how science is a common heritage that unites all humanity, even as it respects cultural diversity. There is no aversion-filled rhetorical claim, like ‘the West stole calculus’ etc. Instead, there is a detailed explanation of what actually the Kerala school of mathematics achieved. Here is an excerpt:

This book forms a narrative of the evolution of various sciences. It is also modular – that is, each ‘module’ can be read independently. There are box items which highlight the important points. All this make it a must-read for every lover of science-history as well as every student of Indian history.

'History of science' is a neglected area in our teaching of history. It will be really a tribute to the physicist if this book is used by NCERT in developing its curriculum.

Dr. Padmanabhan also had a philosophical bend of mind laced with humour. His essay on the Bhagavad-Gita is a must read. It is available online on his official IUCAA website. The article is powerful. But if one is either the left-woke or trad-woke, then this article is PG-rated and better not read. But read it if you want to know how a hardcore no-nonsense physicist can approach the Gita, even if he were a non-believer, with reverential intensity.

Consider just these excerpts:

One wonders what a great social scientist the astrophysicist would have made. He points out a core Gita vision: at once the basic urge in all religious movements (and note he includes Marxism in that) comes from a need to achieve happiness and if genuine, even through Marxism you ultimately come to Krishna.

And if you thought that he would gloss over the Personal God aspect of Gita, he is not. He embraces the true nature of Gita with an ease of the movements of a Bharatnatyam dancer:

And then this:

The last line defines it: ‘Real Gods don’t feel insecure if you tell them they do not exist.’ That should define the Gods and Goddesses of Sanatana Dharma. Otherwise, in what other culture can you see ‘ninthaa’—scolding and disrespecting with bhakti—become a form of stuti, worship? His essay on Gita definitely is an important classic and should deserve as much respect among Hindus as his science works deserves in the physics community.

And his dedication in his book After the First Three Minutes, reads: ‘to my daughter Hamsa, who thinks I should be playing with her instead of writing such books.’

Today, that daughter is also an astrophysicist. Perhaps she may come out with an updated version of After the First Three Minutes with the latest discoveries and theoretical models – as a befitting tribute to her father whose work and life have made all Indians proud as has his sudden demise made us all deeply sad.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest