Science

James Webb Space Telescope Has Taken Its First Image Of A Planet Outside Our Solar System

- Astronomers have used the James Webb space telescope to take a direct image of a super-Jupiter mass exoplanet.

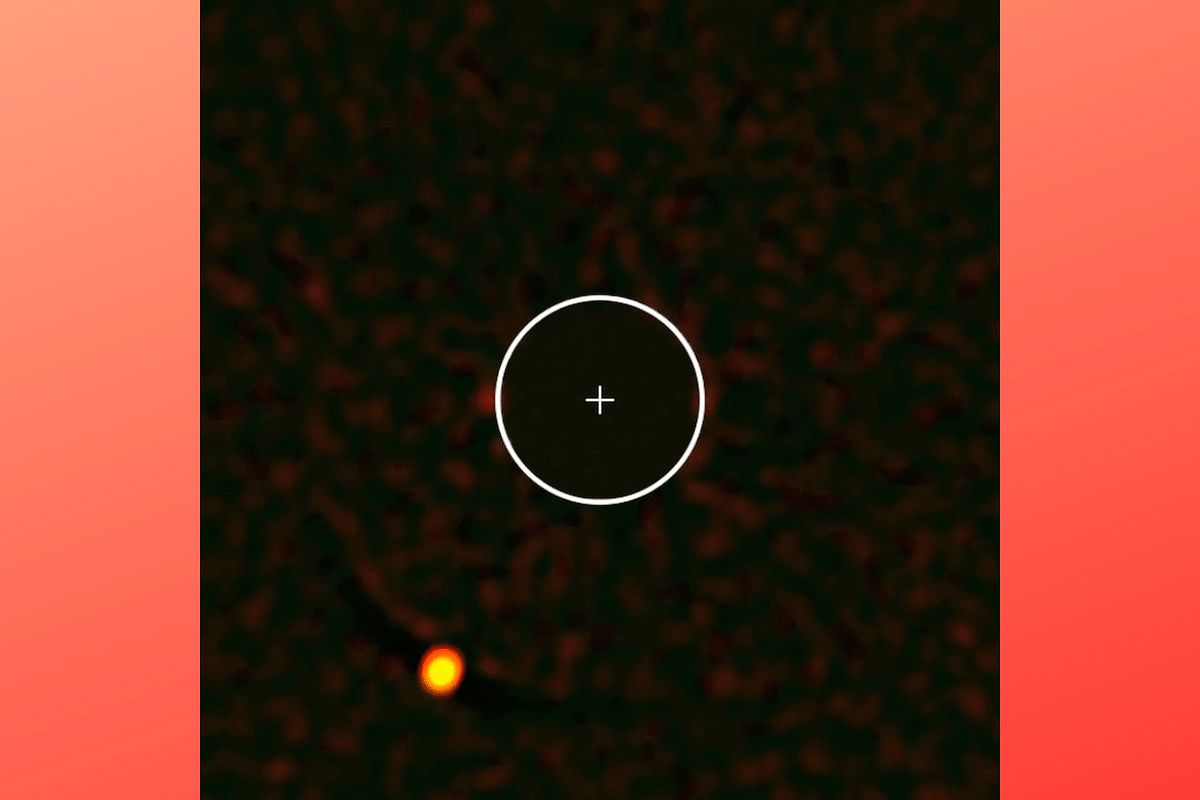

HIP 65426b, as captured by the SPHERE instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. (Photo: ESA)

The latest in the James Webb space telescope’s revelations is the direct image of a planet outside our solar system, called an exoplanet.

This is not the first direct image ever of an exoplanet — the Hubble Space Telescope has done it previously. However, this is Webb’s first (with a promise of many, many more) and the first ever direct detection of an exoplanet beyond 5 micrometres (µm).

Webb’s capture of the super-Jupiter mass exoplanet tells us where we could be headed in our journey to study distant worlds.

The name of the exoplanet is HIP 65426 b. It is a gas giant, meaning that it’s a large planet mostly composed of helium and/or hydrogen. For reference, the gas giants in our solar system are Jupiter and Saturn.

HIP 65426 b goes around its parent star, HIP 65426 (a glimpse into the naming convention), which is close to 400 light years away. The planet is about six to 12 times the mass of Jupiter.

Unlike Earth, it has no rocky surface and is uninhabitable. Aged about 15 to 20 million years old, it’s like a child in comparison to Earth, which is more like a grandpa at 4.5 billion years old.

The star-planet system was captured using Webb’s Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) from 2 to 5 µm and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) from 11 to 16 µm.

NIRCam is Webb's primary imager that covers the infrared wavelength range 0.6 to 5 µm. MIRI covers the wavelength range of 5 to 28 µm. Both are equipped with coronagraphs, which help to block out starlight so that the exoplanet is captured directly.

The United States’ space agency, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), has shared the image of the exoplanet in four different bands of light:

Purple, at 3 µm, using NIRCam

Blue, at 4.44 µm, using NIRCam

Yellow, at 11.4 µm, using MIRI

Red, at 15.5 µm, using MIRI

“These images look different because of the ways the different Webb instruments capture light. A set of masks within each instrument, called a coronagraph, blocks out the host star’s light so that the planet can be seen,” the NASA blog sharing the image explains.

The small white star in the four images represents the host star.

It helps, for direct imaging, that the exoplanet is 100 times farther from its host star than Earth is from the Sun. (The Sun-Earth distance is about 150 million kilometres or 1 Astronomical Unit.) Otherwise, host stars are so much brighter than their planets that a direct image of the planet becomes a big ask.

The planet is also more than 10,000 times fainter than its host star in the near-infrared, and vastly more so in the mid-infrared.

Still, starlight was all that Aarynn Carter, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, would see at first. “… but with careful image processing I was able to remove that light and uncover the planet,” he said, as quoted in the NASA blog.

Carter is the first author of the preprint, available online, presenting the observations and analyses made around HIP 65426 b using Webb.

Astronomers discovered the planet HIP 65426 b in 2017 using the SPHERE instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. In fact, it was the instrument’s first ever catch.

The planet was captured then in much shorter infrared wavelengths of light as compared to the images taken by Webb.

The fact that Webb is way out in space, 1.5 million kilometres from Earth, gives it the advantage of avoiding the intrinsic infrared glow of Earth’s atmosphere. Webb’s image, therefore, reveals new details outside of the scope of a ground-based telescope.

Webb, as per the HIP 65426 b preprint, “is exceeding its nominal predicted performance by up to a factor of 10.” It offers "an transformative (sic) opportunity to study exoplanets through high contrast imaging,” the paper submits in conclusion.

Webb’s capabilities are being demonstrated as part of the Director’s Discretionary Early Release Science Programs. Observations in six science areas, made during the first five months of Webb’s operations, have been designated for early release. One among them is “Planets and Planet Formation.”

This is only the beginning in Webb’s “significantly more than a 10-year science lifetime.” Not only do we stand to obtain many more such exoplanet images, but also we could learn about new ones not present on our existing exoplanet catalogue.

Only about a week ago, it came to light that Webb had captured the first clear evidence for carbon dioxide in a planetary atmosphere outside our solar system. That was its first exoplanet find, per se. It has mouth-watering implications for our knowledge of the birth and evolution of planets in the future (read more).

More than 5,000 exoplanets have been discovered and "confirmed" till date. Thousands of other candidate exoplanets are in the queue to be confirmed or denied.

While the typical understanding of an exoplanet is that it is a planet going around a host star outside of our solar system, an exoplanet need not be tethered to a star. It could even be a free-floating planet orbiting the galactic centre rather than a particular star.

Webb is an international mission led by NASA in collaboration with its partners, the European Space Agency and Canadian Space Agency.

Decades in the making, the space telescope was launched on Christmas Day of 2021 and now lies at the service of science at the second Sun−Earth Lagrange point.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest