Science

Two New NASA Missions To Venus — What Do We Expect To Learn And Why It Matters

- NASA is sending two new missions to study Venus. Here's an in-depth look at the DAVINCI+ and VERITAS missions and why exploring Earth's sister planet is important.

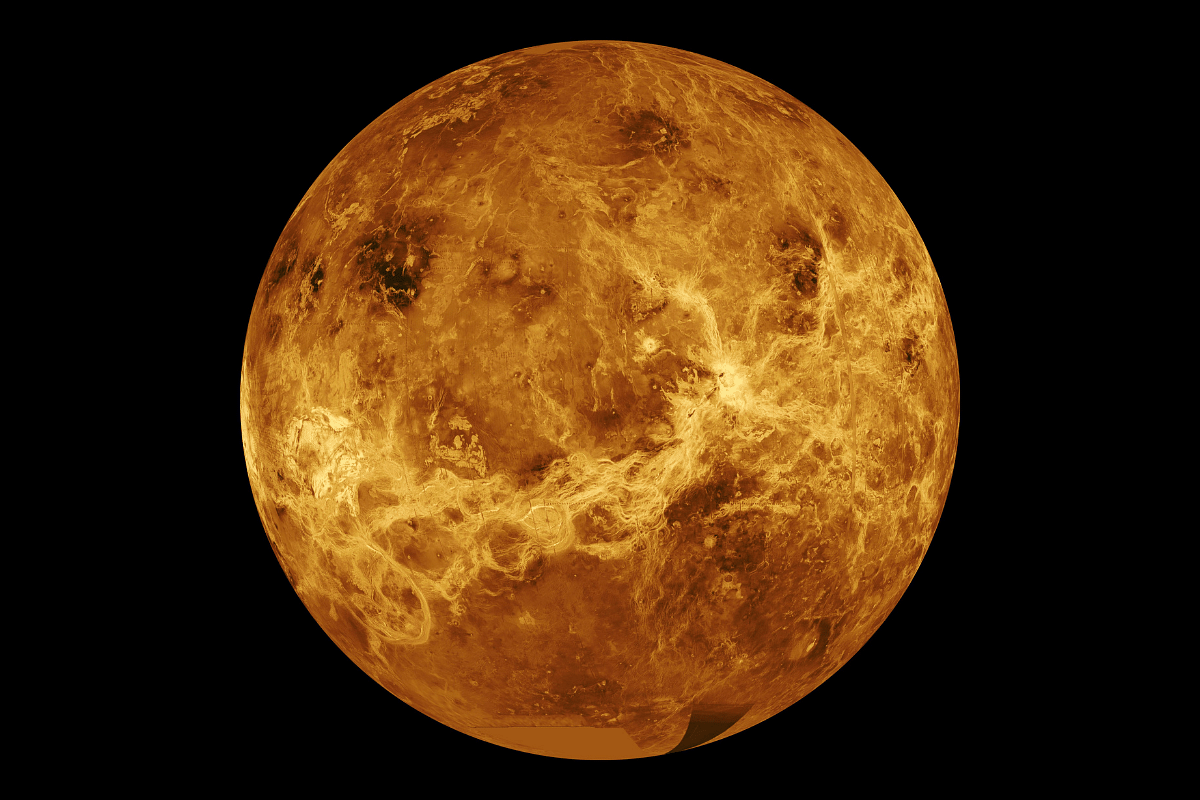

Computer simulated global view of Venus; Source: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory-Caltech

The United States' space agency will be returning to Earth’s neighbour and sister planet Venus this decade — after a pause of about 30 years.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) announced that it has selected two new missions to Venus — DAVINCI+ and VERITAS.

These two approved missions were part of the four concept solar system science missions selected by NASA in February last year. The other two are Io Volcano Observer (IVO) and TRIDENT — designed to explore Jupiter’s moon lo and Neptune’s icy moon Triton respectively.

These missions came from the NASA Discovery Program, which provides a platform for scientists and engineers to come together to design space missions to enhance our understanding of our solar system.

Of the four, the two sister Venus missions have received the green light so far.

When we were in school, Venus, Earth, and Mars comfortingly appeared one after another as we counted down the planets of our solar system.

In this rocky triad, we are always learning something new about Earth, courtesy it being our home planet, and the neighbouring red planet, Mars, which has been the subject of many exploration missions for decades.

But Venus appears to have not received as much love or attention, at least in recent years.

“Of all rocky planets that are in our neighbourhood, (Venus) is the one planet we know the least about,” Dr Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA Science Associate Administrator, said in a NASA Science Live broadcast introducing the new missions.

But with DAVINCI+ and VERITAS, this is set to change as the missions will shine the light of enquiry once again on the second rock from the sun.

The two missions can help expand and update our existing knowledge of Venus — and, in the process, help us learn more about Earth, our extensive planetary backyard, and even planets beyond our solar system.

There are over 4,400 confirmed exoplanets today — and more than 6,000 candidates yet to be confirmed — some of which are rocky planets with thick atmospheres.

“We don’t know our Venus, so how can we understand these other Venuses all over the galaxy, around other stars?” Dr Zurbuchen says.

The last time NASA visited Venus was with the Magellan orbiter in 1990. This probe was the first to image the entire surface of Earth’s twin. Besides, it returned 1,200 gigabits of data, unprecedented for a single mission at the time.

Since then, NASA has stayed away, but Europe and Japan have had their rendezvous with Venus through the European Space Agency’s Venus Express and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Venus climate orbiter Akatsuki respectively.

Venus Express arrived at the planet in 2006 and remained operational for over eight years, with the mission ending in 2014. Akatsuki, on the other hand, entered Venus orbit in 2015 and the mission is still in progress.

After over three decades, NASA is preparing to make a return to Venus.

DAVINCI+ — short for Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging — will measure the planet’s atmospheric composition and try to find out whether Venus ever had an ocean in the past. A burning question for the hot planet, no pun intended.

The probe will descend through the Venusian atmosphere, from the cloud tops to the surface, making measurements along the way.

It will be like a “flying rover chemistry lab”, Dr James Garvin, the principal investigator for the DAVINCI+ mission, explains.

“Our spacecraft will unravel the history of the key chemical constituents of the atmosphere — which are like the fingerprints of the process locally. The atmospheric record will tell us the history of past lost oceans,” he says.

Dr Garvin works at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The spacecraft will send back high-quality images of geological features on Venus that may be comparable to that on Earth. These features, which may be analogous to Earth’s continents, are known as “tesserae”.

The mission is expected to last a little over two years.

By its name, the DAVINCI+ mission honours the Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

“Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa — one of the most famous paintings of all time. We think there’s a 'Mona Venus' waiting. And we want to discover that together for all of humanity. Wouldn't that be beautiful?” Dr Garvin asks.

VERITAS — short for Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy — will attempt to understand why Venus developed differently than Earth.

“On VERITAS, we want to get a global view of the surface of Venus. We’ll be peeling back the clouds using special instruments to see through the clouds and revealing the geologic history. We are looking for processes that are active today,” Dr Susanne Smrekar, the principal investigator for the VERITAS mission, said on NASA Science Live.

The VERITAS mission will involve mapping the surface of Venus, from which we can receive 3D renderings of the planet’s topography. According to NASA, we will be able to learn about Venus’ rock type and confirm whether processes like plate tectonics and volcanism are still active there.

Data from the spectrometre on board the spacecraft will help us get a thermal signature for recent volcanism. In addition, there will be a search for gases — water vapour in particular — coming out of active volcanoes and releasing into the atmosphere.

Gravity data will also be collected by the VERITAS mission to learn more about the core and mantle of Venus.

On the whole, VERITAS will try to get an unprecedented look at the surface of Venus, which is said to be made up of vast plains holding up high volcanic mountains and wide ridged plateaus.

While VERITAS is all about the surface, DAVINCI+ will be all about the atmosphere, VERITAS will get the global view and DAVINCI+, the close-up look.

Dr Smrekar explains that our ideas about Venus, accumulated from decades ago, are outdated.

Through VERITAS, which is Latin for “truth”, the aim is to take new instruments, with more refined capabilities than the ones used all those many years ago, to Venus and reveal the truth about Earth’s sister planet.

It will take two years after VERITAS gets to Venus before data collection can begin. Then, it will acquire science data for three-and-a-half years.

As with any planetary science mission, learning about Venus will provide an opportunity to learn more about Earth as well.

From the new data and insights expected to come in from these two missions, we’ll be able to understand why Earth is unique and what explains its exceptional habitability.

Venus is believed to have started out like Earth, but the two sisters took very different paths. While Earth afforded the luxury of a comfortable life for over three billion years, Venus today is piping hot, has toxic air, and the pressure there is 90 times higher than on Earth.

Even the dramatic NASA trailer for the two missions described the planet as “hellish” and “unforgiving”. What changed?

Dr Smrekar, who works at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, says data from Venus can help answer this mystery and look for similarly habitable planets around other stars.

Last year’s finding of phosphine in a section of the Venusian atmosphere some 50 kilometres above the surface also adds a dash of excitement to exploring the planet again.

The phosphine discovery sparked the unlikely possibility of life floating in the clouds of Venus, since phosphine is considered a marker of life.

Even if it turns out not to be life, a search for phosphine on Venus can lead us to other interesting places, such as unfamiliar chemical processes.

DAVINCI+, according to Dr Garvin, is capable of detecting phosphine.

“DAVINCI has two analytical chemistry experiments; one can detect phosphine throughout the entire atmosphere, especially from the lower clouds all the way to the surface — where no species with phosphorus has been detected. So we will be looking for that with exquisite detail,” he says.

But he also added that the probe will be able to catch more than just phosphine. There could be other trace gases that are equally interesting but not discovered yet. By revealing the chemical context of Venus, DAVINCI can lift the veil off other, similar things unknown.

The missions will additionally be accompanied by a couple of technology demonstrations. The JPL-built Deep Space Atomic Clock-2 will fly on board VERITAS.

"The ultra-precise clock signal generated with this technology will ultimately help enable autonomous spacecraft maneuvers and enhance radio science observations," says the NASA announcement.

The DAVINCI+ will carry the Compact Ultraviolet to Visible Imaging Spectrometer (CUVIS). This technology will measure ultraviolet light using a new instrument based on freeform optics.

According to NASA, observations from CUVIS will shine a light on the nature of the unknown ultraviolet absorber in the atmosphere of Venus that gobbles up to half of the solar energy coming in.

The NASA launch to Venus is likely to happen in the period of 2028 to 2030. Depending on how close Earth is to Venus, the journey can take anywhere from four to nine months. But NASA will be targeting the "sweet spot" of six months.

The Venus missions have a budget of roughly $500 million each for the development phase.

Given that the launch is set to happen towards the end of this decade, there are likely to be at least two to three Venus visits from Earth preceding the NASA launch.

California-based Rocket Lab has plans for a privately funded Venus probe in 2023. Its goal is to see if there is life in the Venusian clouds.

Next on the timeline would be India’s Venus mission, called Shukrayaan-1.

Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) will be sending an orbiter to the planet to study its surface and atmosphere for four years.

It was earlier scheduled to launch in 2023, but delays on account of the pandemic may have set it back by about a year.

Russia too is planning a return with its Venera-D mission, which is expected to comprise an orbiter, a lander, and atmospheric balloons. The mission will investigate Venus’ atmosphere and its surface geology and chemistry. It may launch in 2026.

Going by the signs, Venus is set to become a hot spot for future space exploration missions — and this is after having been overlooked for well over a hot minute.

Some would say better late than never.

However, the time is right, as even beyond localised understanding, acquiring adequate knowledge about Venus will help in decoding the many ExoVenuses that we stand to discover with the upcoming space-based James Webb telescope.

And just maybe, we'll learn why Earth-like worlds near and far end up with contrasting fates to that of Earth.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest