World

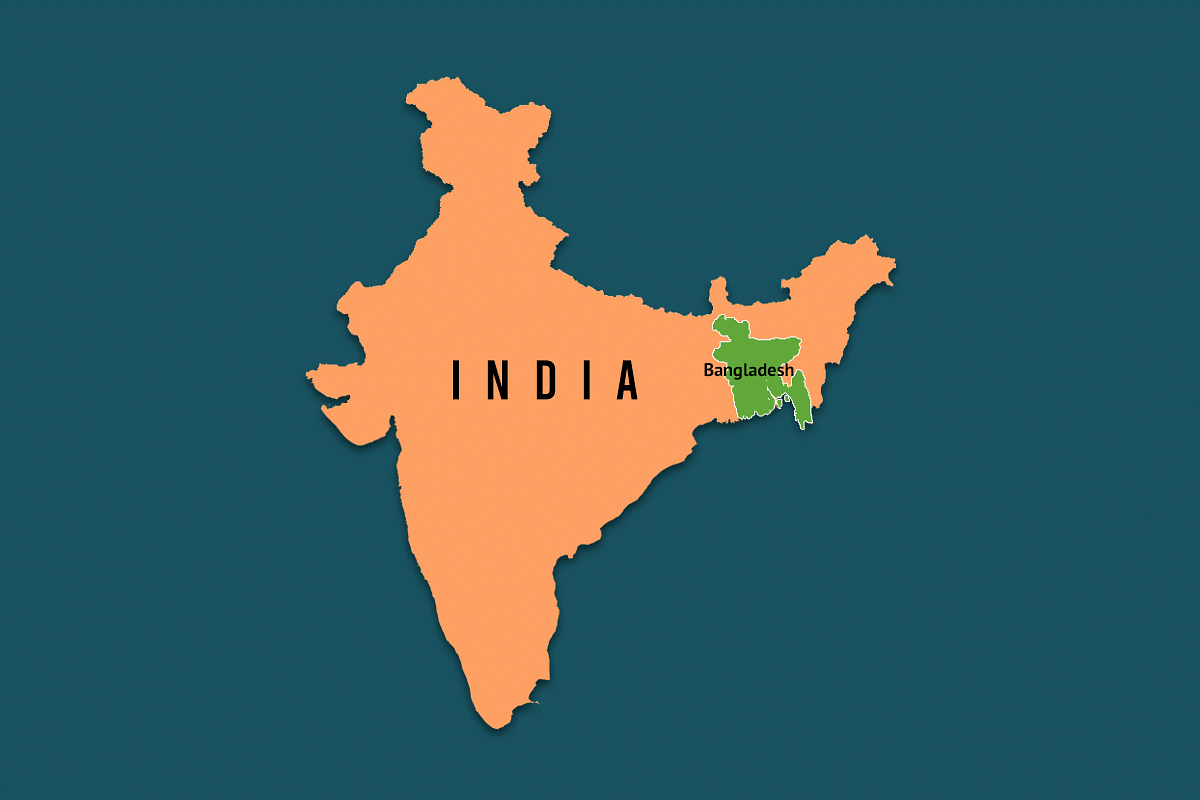

50 Years Of India-Bangladesh Relationship: Changed Realities, Unchanged Value

- It was 50 years ago when, after the surrender of the Pakistan army in Dhaka, Bangladesh was born.

- Here is a short summary of five decades of the India-Bangladesh friendship.

India Bangladesh Relations

Half a century is no small time in the conflict-ridden history of India and its neighbourhood. From that perspective, the 50 years of India-Bangladesh friendship deserve special mention. The task ahead is to widen the scope of cooperation, particularly economic relations, to optimise the benefits of friendly relations between the two governments.

As the largest and most powerful economy in the region, India has a major role to play in converting government-to-government initiatives into a business-to-business and people-to-people relationship. Substantial attention has been paid to these areas over the last decade. However, a lot more is to be done, if we want to cement our ties.

Naturally integrated

Barring a smaller part (that has more in common with Myanmar), historically, geographically, socially, genetically, Bangladesh is inseparable from India. A total of 54 major rivers flow from India to Bangladesh. Not only the river water, Bangladesh shares basins of two of the largest rivers – Ganga and Brahmaputra – of the region.

The rise of the Indian economy, its growing push to mitigate climate challenges, unprecedented focus on harnessing renewable energy (particularly solar), rising military power, and its growing importance as a balancing factor in regional geopolitics are in the interest of Bangladesh.

Similarly, a healthy, prosperous, and politically stable Bangladesh serves Indian interests. Thriving bilateral trade and connectivity, cross-investments, a wide network of regional value chains etc., are the only sustainable solution to prevent illegal immigration and informal trade and make India’s over borders more secure.

An unstable Bangladesh can create serious troubles for India, as was evident in 1971. While the Bangladesh liberation army (Mukti-Bahini) was fighting for freedom from Pakistan; crores ran to India for safety. The 82 km Jessore Road, which connects Kolkata with the largest border gate between the two nations at Petrapole, took the shape of a refugee camp.

The human tragedy was immortalised by American poet Allen Ginsberg in “September on Jessore Road”:

Three months later, on 3 December 1971, India declared war against Pakistan. This was the third conflict between the two neighbours since 1947. Pakistan was the first to pull the trigger by launching an airstrike. India entered East Pakistan. On 16 December, over 90,000 strong Pakistani Army in Dhaka surrendered to India.

On 6 December, before the war was over, India recognised the birth of a new nation. That was way before any other major economy recognised Bangladesh. Pakistan accepted the sovereignty of Bangladesh in February 1974. Beijing waited till August 1975. Both China and USA supported Pakistan in Bangladesh’s Liberation War.

Zero conflict

For fifty years since, the 4,000 km long India-Bangladesh border hasn’t seen any major armed conflict. The relationship was not equally warm all across though. The creation of Bangladesh proved the fragility of the two-nation (for two religions) theory behind the Partition in 1947. However, it also created a set of wide contradictions within.

The assassination of Mujibur Rahman in 1975 and the 15-year army dictatorship saw Bangladesh slipping back into the hands of the same religious-political groups who once sided with Pakistan.

A highly revengeful, bipartisan political atmosphere didn’t help the cause of democratic institution-building after army rule officially ended in 1990. Power was never smoothly transferred from one democratically elected government to the other, over the last three decades.

India-Bangladesh relations were filled with mistrust and suffered stagnancy for a larger part of this period. This is partly due to small-country syndrome, partly due to the historic failure of the Indian economy to act as a growth magnet to the region, and significantly due to the religious-political environment in Bangladesh.

India’s loss was China’s gain. Beijing made rapid inroads in Bangladesh after 1975 and particularly after 1990 when the Bangladeshi economy started growing at a decent pace. Until 2017, the Bangladeshi army was solely dependent on China. The trend was disrupted by India-Bangladesh defence cooperation treaties in 2017.

For all practical purposes, India came back to the reckoning in Dhaka, after the current Sheikh Hasina government came to power in 2009. A lot has changed since then. The two countries worked in wide-ranging areas to reduce the scope of future disputes and optimise economic integration for mutual good.

Economic integration

The territorial dispute is the most common source of trouble between neighbours. This is particularly true for China which is in the habit of pushing the boundary and renaming foreign territories in Chinese.

Leave aside disputes with India and Taiwan; Beijing has border issues with the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, Singapore, Brunei, Nepal, Bhutan, Laos, Mongolia and Myanmar.

In sharp contrast, India and Bangladesh have settled almost all disputes over the maritime and land boundary between 2014 and 2015. The land boundary pact deserves mention as it involved a net (national) loss of Indian territories as were defined during Partition.

The developments are far more dramatic on the economic front. India and Bangladesh had seven rail links from pre-Partition days. They were snapped after the 1965 war between India and Pakistan. Now five rail links are restored. More are underway. This includes a new link from Tripura to Chittagong port in Bangladesh.

Passenger rail services were restored in 2008 by Dhaka-Kolkata Maitree Express. Today, at least three sets of trains are connecting Dhaka and Khulna in Bangladesh with Kolkata and New Jalpaiguri in West Bengal.

For two neighbours sharing the same coastline, there was no direct ship movement till 2015, when India and Bangladesh entered a coastal shipping pact. This, coupled with amendments to the inland-water transport pact, opened wide opportunities for low-cost multi-modal cargo movement.

Bangladesh has an inter-continental cable landing station at Cox’s Bazar. In 2015, India entered an agreement to buy 10 GB of bandwidth from Bangladesh. It is helping ensure digital connectivity in northeastern India.

The results are visible in the trade figures. Between 2009 and 2019, India’s exports to Bangladesh increased by nearly four times - at the same rate as China - to reach $8.2 billion from as low as $2.1 billion. Bilateral trade increased from $2.3 billion to $9.4 billion.

The quality of trade has also undergone a sea change. A decade ago, India Bangladesh trade was dominated by primary products. Bangladesh mostly imported commodities like cotton, rice etc. and exported betelnut, fish and others. Today manufactured items dominate the trade.

Over the last three years, the ready-made garment (RMG) industry in Bangladesh found a growing market in India. From a minuscule $0.2 billion, Bangladesh’s total exports to India reached $1.2 billion in 2019 (ITC Trade Map). In comparison, Chinese exports reached $17 billion in 2019, and imports were only $1 billion.

According to India’s Commerce Ministry, Bangladesh exported $1 billion worth of goods in the Covid year of 2020-21 (April-March). Trade is zooming in 2021 as Bangladesh touched the $1 billion export mark to India in the first seven months (April-October) of 2021-22.

Clearly, the measures undertaken by India in removing duty barriers and improving trade logistics are working. India-Bangladesh economic cooperation is now the fulcrum of regional cooperation between BBIN (Bhutan-Bangladesh-India-Nepal) countries.

India’s trade with BBIN is witnessing faster growth when compared to SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) and BIMSTEC (The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation).

Yeh Dil Maange More

India-Bangladesh relations have taken a great leap forward over the last decade. From one or two flights between Kolkata and Dhaka, Bangladesh now has vast connectivity with many Indian cities. It is also the top source of medical tourists to India. The total number of passenger arrivals increased a few times.

But that doesn’t mean we have optimised the integration opportunities. According to ITC Investment Map, annual FDI by Indian companies in Bangladesh hovered in the range of $115-120 million during 2017-19. This is significantly high when compared to less than $8 million FDI in 2009. However, the figures look insignificant compared to India’s annual outward FDI of $18-20 billion.

One major problem here is severe restrictions imposed by Bangladesh on foreign exchange outgo. It cuts both ways. A foreign investor faces problems in taking out profits and dividends and/or investing in some other country through Bangladeshi operations. Not to mention that Bangladeshi companies also miss out on the opportunity to invest overseas.

There is, however, a catch. The Bangladeshi government relaxes such norms in specific cases. As a parallel development, there is a sudden increase in Chinese FDI in Bangladesh to $1 billion in 2018 and $625 million in 2019. China was behind India in FDI till 2017. What is restricting Indian companies from investing in Bangladesh and why cannot be removed? those barriers

India’s federal structure is also posing challenges to optimise the potentials of India-Bangladesh relations. All central initiatives for highway widening, improvement in trade infrastructure and even the Teesta water-sharing agreement are either resisted or delayed in West Bengal, which shares a 2,000 km border with Bangladesh.

India cannot afford domestic politics to dictate terms on national interests and it is high time we resolve issues with such problems.

Last but not the least, memories of 1971, cultural nationalism, the Liberation War against Pakistan and the early promises made by the Bangladeshi constitution in 1972, must not dictate India’s strategy. It’s a changed country. And, we must be aware of the ground realities.

Over the last 50 years, India’s response to Bangladesh was more need-based. It is time we have a long-term policy to strengthen the friendship.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest