World

India Pursues A New Investment Arbitration Regime To Protect Itself

- Forced by adverse international arbitration awards, the developing economies are now looking to establish their own arbitration frameworks to protect their regulatory and economic freedom.

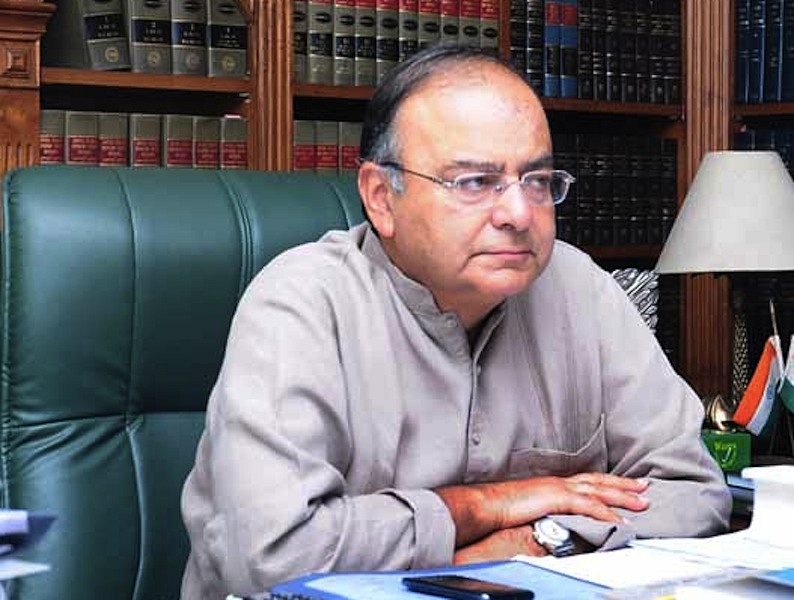

Finance Minister, Jaitley

Recently, at the conference on ‘International Arbitration in BRICS’, Indian Finance Minister Arun Jaitley was unequivocal in pitching for a separate arbitration framework for the BRICS countries or the emerging economies. He was clear that India, like other developing economies, has been a victim of the inherent structural bias that prevails in the traditional frameworks of international arbitration.

Contrary to the perception, this stand of Jaitley’s is neither new nor isolated. In fact, it is even consistent with India’s stand since 2012, when the then Finance Minister of India indicated that India will renegotiate all its Bilateral Investment Treaties (BIT) from scratch. A new model BIT was approved by the Cabinet last year (2015) and it was indicated that it will be used to renegotiate all future BITs.

Subsequently, early this year, India terminated its BITs with 57 countries and requested 25 other countries for a joint interpretation. All these BITs contain the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) framework, which allows a private investor to bring a claim directly against the State in which the investment is made for any action the investor believes to be in breach of international standards.

This is not the first time a country has terminated BITs or withdrawn from ISDS frameworks. There has been a global movement to this effect.

The Growing Opposition To The ISDS

In 2007, faced with a number of claims, Bolivia denounced the Convention for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID)— becoming the first country in the world to do so. Many other Latin American countries followed Bolivia and denounced ICSID, i.e., by withdrawing their consent. Further, these countries, along with others like Brazil, have taken steps to terminate their existing BITs with most of the developed countries. In Asia, along with India, Indonesia has terminated (did not renew) its BIT with more than 20 countries and is taking steps to terminate the rest in the near future. Australia has also been debating opting out of the BITs since 2010. South Africa and a few other countries in Africa have also decided to terminate the BITs.

Why Such An Opposition?

The trigger points for the termination of BITs may be different but the underlining anguish remains the same. The protection given under BITs, which allow a private investor to bring a claim against the State where the investment has been made, have been interpreted to affect the regulatory freedom of the countries. This regulatory freedom is an integral part of the economic sovereignty of the country.

Further, there has been some evidence that the Tribunals constituted under the BITs have travelled beyond their mandates and sit in review of almost all the decisions taken by the country or its judicial organs. Like David Suzuki once remarked about the BITs giving a little too much away, in most of the BITs, the foreign investors directly invoke the ISDS clause of the BIT without approaching the domestic courts or tribunals. In a few cases, especially in the case of Latin American countries, these proceedings have been used successfully to force a regulatory chill in the country.

India started reconsidering its stand on the BITs after the famous White Industries award, which ordered India to pay damages for failing to provide the foreign investor effective means to seek remedy under the domestic framework. There, the courts had delayed enforcement of an award for the last nine years. The recent Devas award (The Antrix-Devas Case), which also went against India, has only fast-tracked the process of exiting the traditional framework of ISDS.

It is important to note that India is not yet a party to the ICSID. It is also important to note that India is not against BITs but against the ISDS frameworks contained in earlier BITs. In fact, the Indian Cabinet has approved a new BIT with Cambodia based on the new model BIT in July.

What Does The Future Hold?

There is a growing demand among developing countries to enter into separate agreements and/or frameworks which understand their basic needs and requirements. The Latin American countries were always reluctant to the concept of ICSID; at the 1964 Annual Meeting of the World Bank, these countries had even unanimously voted against such a proposal (the famous ‘Tokyo No’). In 2009, Ecuador proposed that the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) manage the arbitration centre, which was readily accepted by all the other attendees. The centre, provisionally called as UNASUR International Centre for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (UNASUR Centre) has been in the news for the last five years. There have been meetings and conferences to finalise the details and principles that will serve as a governance framework for this centre. Finally, after six years, there are indications that the centre will finally be notified. While the UNASUR Centre will initially cater to only Latin American countries, its facilities will eventually be available to all countries.

Similarly, the BRICS Arbitration Centre (BRICS Centre) has been created to address and reinforce this idea. While limited to BRICS countries in its initial phase, it will be available to all the developing countries in the future. While the idea may seem new to some, India has been toying with this idea since the last two years. The views of three member states, namely India, Brazil and South Africa as developing nations, is clear—they will prefer an arbitration framework that is receptive and which respects the regulatory freedom that developing and emerging nations need.

However, while Russia has been facing a lot of heat in investment arbitration, where the fallout of the Yukos Expropriation has been too huge to control, it has still not commented on any possible deviation from the existing BIT and ICSID-based arbitration system. China, as the history shows, will reserve its comments till the proposal is debated through the formal channels.

The primary goal of such an arbitration tool, in UNASUR as well as BRICS, will be to protect the regulatory freedom of the government. For instance, the UNASUR Centre negotiations have said that the centre will be a body full of respect for state sovereignty, both jurisdictional and legislative. The principle, it is expected, will be applied in the context of fiscal, tax and national security measures in the absolute sense. The levy of tax is a completely sovereign and revenue-oriented function and the belief among these countries is that no ad hoc tribunal should have the power to decide on such matters. We can also expect that such an arbitration centre will also provide complete autonomy to states to decide whether any action taken is for “public purpose” or for “national security”, i.e., once the state has taken an action in regard to these two purposes, the tribunal will not review the same.

There have also been indications that such arbitration centres will require the foreign investor to approach the domestic courts in the host country in a serious manner before invoking its jurisdiction. Such an arbitration framework may also have country-based Investment Courts for speedy and quick resolution of disputes.

Going Back To The Calvo Doctrine

The future, thus, may only be a return to the past. The ultimate goal, as it appears, is to go back to the tested Calvo Doctrine, i.e., foreign investors will only get the protection that is available to domestic businesses and nothing more. The foreign investors may get incentives to invest, but not the additional protection that has become a norm in the last four decades. It would be interesting to see how developed countries react to the widespread denunciation of the ICSID and the emergence of alternate forums like BRICS and UNASUR Centres.

Another issue will be the possible confrontation between the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and these frameworks (though it’s a very remote possibility due to a lack of overlap in membership). One can only wait for the UNASUR and BRICS Centres to take shape to see how these two institutions will change the face of investment arbitration as we know it.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest