World

Nate Silver And Company May Be Erring Again; Polling Errors Mask A Possible Trump Win

- The bottom line is: it could be a veritable Trump sweep if the polls are wrong, though ironically, the polls would still be wrong even if Biden wins.

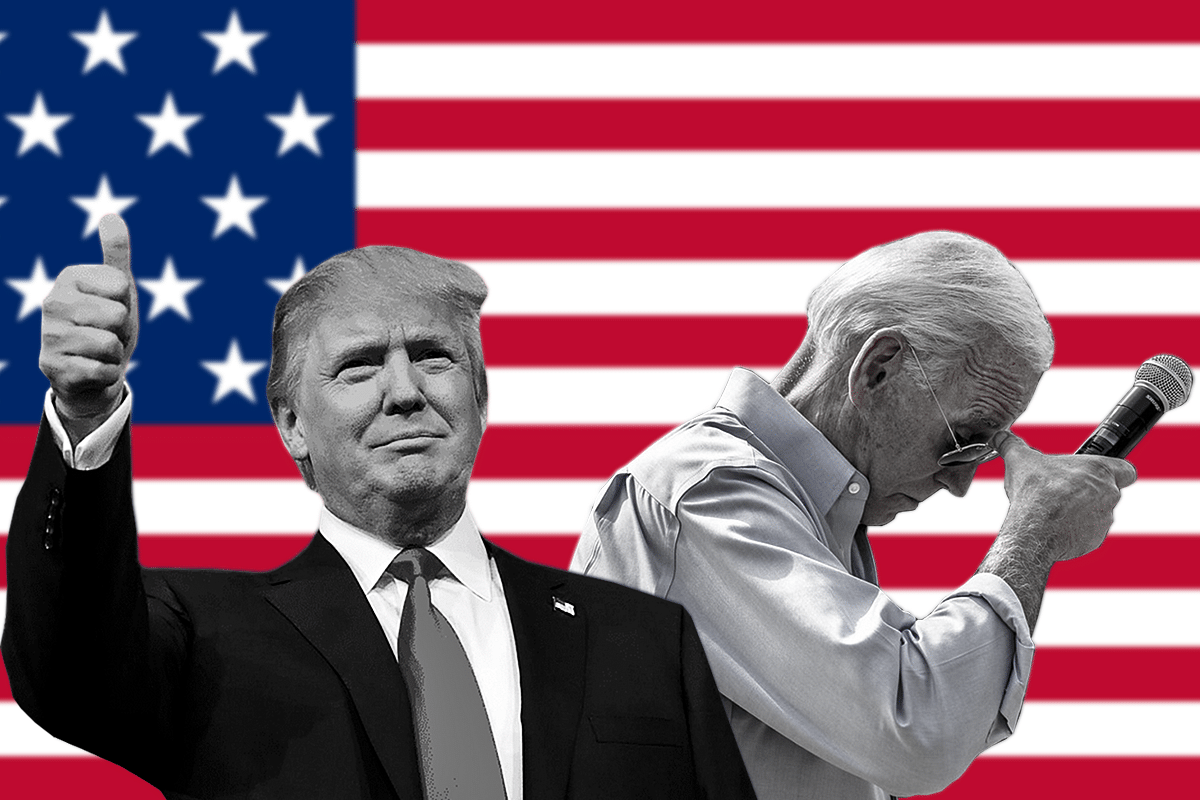

US President Donald Trump (left) and Democratic Party’s presidential candidate Joe Biden. (Illustration: Swarajya Magazine)

Something strange is happening across America. Pollsters and journalists seem less capable in 2020 of feeling the pulse of the people, and look more like the Democratic Party’s loyal handmaidens.

As a result, public opinion has it that Donald Trump and the Republicans will lose badly to Joe Biden and the Democrats, in Tuesday’s presidential elections.

But these polls are flawed.

In many crucial cases, they are in fact badly flawed. So in this piece, we shall identify these polling flaws, analyse them, and make a fresh election forecast accordingly.

This is important, because if the polling errors truly exist (for whatever reason), then the prediction changes dramatically from a Biden win to a Trump re-election.

The Issues

A little history first to understand how these errors crept into the American polling process.

Most pollsters got the 2016 election embarrassingly wrong by large margins at the state level, even if their aggregate national forecast was right. This contradiction resulted in Hilary Clinton losing, even after getting more of the popular vote than Donald Trump.

There were two reasons for this.

First, Clinton’s vote share ballooned because she got an inordinately large share of the votes in heavily populated Democrat states like California and New York.

This is a bit like Gujarat 2017, where the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) got over 49 per cent of the vote, but still nearly lost; the reason is that their amazing urban victories (with over 60 per cent of the vote) were nearly nullified by a number of very tight losses in rural areas to the Congress.

As Congress leader P Chidambaram ruefully said later, a few votes in 20-odd seats could have changed the story entirely in the party’s favour.

Second, American pollsters completely missed the political sentiment of lesser-educated white people.

This segment turned out to be a sizeable chunk of voters, who were intensely loyal to Trump. It is they who turned out in large numbers in 2016, to gift Trump those key states, which Barack Obama had swept with ease in 2012.

A fitting analogy is Uttar Pradesh in 2014: most analysts, including this writer, felt that the best the BJP could do there was around 30 per cent of the vote share, and 42 seats out of 80. None of us gauged the startling manner, in which the Jat-Muslim axis crumbled to bits under a Narendra Modi wave, to give his alliance 73 seats with over 40 per cent of the vote share.

American pollsters thought they had missed representative samples because they goofed up their geographical weightage — meaning, focusing more on a city centre rather than a suburb, or vice versa.

To make up, their latest theory now, which they use to arrive at weighted sample spreads, is a ‘fundu’ ghettoisation or ‘herding’ concept. By this, they believe that if they spot one Democratic voter in a particular locality, the thinking is that there would be disproportionately more Democratic voters in the vicinity.

Of course, this is based on the absurd premise that Americans have somehow, suddenly, taken to flocking to postal districts by party loyalty since 2016. Absurd, since if this hypothesis was correct, then America should have witnessed the abrupt, dramatic relocation of dozens of millions of long-settled families, in the past three years. It hasn’t.

Polling Errors

The point is that American pollsters appear to be missing again in 2020, what they missed in 2016: that there was, and is, a distinctive Trump wave. Now, there is no doubt that this wave can be contained by the Democrats, by enhancing voter turnout, counter-consolidation, or enticing voters back to their fold, but that doesn’t make the polls right.

Nothing accounts for the magnitude of polling errors in 2016, except bias or ineptitude, which these agencies appear to be repeating now.

In 2016, they were fairly monumental at times, especially in key states, with margins of error going over 7-8 per cent, and into double digits on occasion.

The first key polling issue stems from a curious observation: up to this week, and without exception, every average poll, in every state in the country, showed a distinct, positive vote swing towards the Democrats. That is a statistical impossibility.

Second, in Minnesota, which Clinton won by a whisker in 2016, the pre-election polls gave her a double-digit lead. They completely failed to spot the two key factors which made it such a close contest: that the Republican vote held rock steady instead of declining heavily as predicted, and, that a full 6 per cent of the Democrat vote switched to ‘others’. They are making the same mistake again in 2020.

Third, in Arizona, which the Republicans retained from 2012 by 3.5 per cent, 2020 polls show the Democrats ahead by 4 per cent, and the Republican vote share down, but with no change in ‘others’.

This makes no sense, because in 2016, the Democrat vote didn’t actually change from 2012. Instead, it was 6 per cent of the Republican vote which switched to ‘others’, to make the race seem tighter than it was. So how can the Democrat vote go up in 2020 without the ‘others’ going down?

No doubt, this being America, pundits will invent some new demographic to explain away this survey puzzle (like female high school graduates under 50 with diabetes, or left-handed male Hispanic seniors who own less than two vehicles). But really, that’s stretching psephology to breaking point. The simpler explanation is that the survey is plain wrong.

Fourth, it is the same in Colorado, where a 6 per cent swing from both parties to ‘others’ in 2016, is left oddly intact in 2020 surveys, while votes somehow shift insularly from Republicans to Democrats.

Fifth, is the ultra-close contest in Florida, which Trump won in 2016 by less than 1 per cent vote margin.

There are two principal reasons. One, the votes of both parties shifted slightly to the ‘others’ in 2016, and Trump won because he lost less votes than Clinton (we saw this a lot in Kerala 2016). This time, the polls predict a continuation of this odd trend, but only by the Republicans. That is another statistical impossibility. Two, The Republican average poll vote share is about 5 per cent too low to digest, and bluntly contradicts pollsters’ claims of it being a tight fight.

Sixth, this same anomaly of a strangely-unchanging ‘others’ component repeats itself in Georgia, to make it seem like a close contest, when actually, the Republicans swung the state easily in the face of two massive Democrat campaigns, successively, in 2012 and 2016.

Seventh, is Michigan, an electorally important state, which Trump won in 2016 by a hair’s breadth, on the back of a massive 10 per cent wave. In 2020, the pollsters have somehow discounted this wave, and called the state for the Democrats. We might have believed them if they said the fight would be close, but current average polls beggar credulity for two reasons: votes shift unilaterally from the Republicans to the Democrats to create a yawning 8 per cent gap, with that very odd ‘others’ column once again remaining curiously untouched.

Eighth, is Minnesota again, from the perspective of the race riots which happened in June 2020. The Republicans held their own in 2012 and 2016, with their 45 per cent vote share remaining untouched, even in the face of Democrat victories on both occasions.

Now, in 2020, the polls show a steep decline in the Republican vote share, while that of the ‘others’ and Democrats go up. This monotony of ‘others’ repeatedly playing havoc with forecasts can no longer be taken as a coincidence; we have to treat it as a significant polling error.

Besides, to think that the race riots will have no impact on voting patterns, in its epicentre, is naivete, sophistry, or foolhardiness.

Ninth, in North Carolina, the Republicans successfully held on to both the state and a 50 per cent vote share in 2012 and 2016. But in 2020, votes shift from the Republicans to the Democrats and, you guessed it, ‘others’, to give the state to Biden. Not possible, since the Democrat vote can’t go up without the ‘others’ vote coming down.

Tenth is New Hampshire, where the Republicans consistently polled nearly 47 per cent in both 2012 and 2016. Trump lost by just 0.3 per cent without the Republican vote share going up, for a very curious reason: because 5 per cent of the Democrat vote went to the ‘others’.

The 2016 surveys, though, were miserably wrong by over 10 per cent. Note: there was no material vote exchange between the two principal parties in 2016.

Still, in 2020, the surveys say that the Republican vote share will swing magically by 4 per cent to the Democrats, and gift Biden a victory margin much larger than the one even Obama got in 2012. Polls which mirror past mistakes, and once again project vast swings and sweeps instead of tight fights, need special scrutiny.

Eleventh is Nevada, which turned markedly Democrat in 2008 for Obama (and in tune with the national mood following Junior Bush’s disastrous wars on terror). Since then, the Democrats’ commanding vote share and margin has declined consistently, with Clinton only managing to retain the state in 2016 by 2.4 per cent (that’s down 10 per cent from a 2008 high of 12.5 per cent).

A bulk of the vote shift was to ‘others’, with the Republican vote share remaining static at around 46 per cent.

In 2020, the surveys show Nevada staying with the Democrats, with an increased vote share. Here’s the catch, though: this victory is based on votes shifting from Republicans to Democrats, with the ‘others’ staying untouched at about 7 per cent. Add to this incongruity is the widespread anecdotal evidence, which points to a Trump wave in the state.

Twelfth is Pennysylvania, where the polling error crossed 6 per cent in 2016, when Trump won a narrow victory (0.7 per cent margin). For pollsters to ignore that and again give Biden a healthy 5-7 per cent lead over Trump, while bring the ‘others’ factor into play once more, is to test belief.

Moreover, this is an oil and gas state; there is no way popular support for the Democrats would go up after Biden announced publicly, that he would ban fracking and end the era of fossil fuels soon. No one votes their jobs away.

Thirteenth, and last, is Wisconsin, when Trump won in 2016 because 5 per cent of the Democrat vote shifted to the ‘others’. Pollsters also underestimated the Republican vote share then, by over 6 per cent. Their overall results were thus off by a whopping 8.7 per cent, and they got the outcome wrong to boot as well. They are making the same mistake again in 2020.

The Forecast

So, how do these many polling inconsistencies come together into a realistic forecast? How do we make a prediction using flawed, non-representative surveys?

A few experts, like Nate Silver, have tried using the 2016 margin of error to reconcile 2020 polls, to predict wins. That’s a fairly bold approach to employ, because it rests on a basic assumption that the 2016 margins of error will remain constant. The simple fact is, they won’t. If anything, polling error margins, which were already atrocious in 2016, are only expected to get worse.

Luckily, the problem doesn’t manifest itself in a majority of the states, where one party is so dominant that it can weather both a large vote swing, and a larger margin of error in surveys (like Massachusetts, where the Democrats lead by nearly 30 per cent, or Oklahoma, where the Republican lead is over 35 per cent).

The problem is in those swing states, called ‘toss-ups’ in American jargon, which will decide the outcome by narrow margins. Here, now that a sizeable portion of America has voted, some pollsters are in fact trying to overcome these errors. And guess what, a few of the latest polls either show Biden’s lead going down fast, or Trump, at last in the lead. But, Americans have a strange, inexplicable tendency to use weekly polling averages, instead of treating each poll as a stand-alone survey.

As a result, since only a small number of polls show Trump ahead, Biden still has an overall healthy lead as per these averaged polls — even in swing states. This approach makes no sense, because if ABP News or Times Now, for example, were to offer divergent forecasts for Bihar, we would analyse each survey independently, instead of taking an average of the two. Or, if the most recent polls showed a particular trend in favour of a particular party, we wouldn’t club it with opposing results from a week before. Using a mathematical average instead would only smother the actual ground realities, under a needless weight of aggregation.

Still, it is what it is. The trick, therefore, lies in identifying the dubiousness of polls by spotting their inconsistencies — especially the infernal ‘others’ component.

With that in mind, the polling errors for each state mentioned above were applied to the latest polls there, to generate electoral outcomes. A subjective, qualitative probability was also then ascribed to each state (like, for example, the improbability of race riots not impacting voting patterns in Minnesota, which is what the pollsters would have us believe).

The results are intriguing:

High probability of a Trump win: Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Trump won all of these states in 2016.

Moderate probability of a Trump win: Nevada, Colorado, Minnesota and New Hampshire. All four were won by the Democrats in 2016, so they would be remarkable upset swings, indicative of a Trump wave, if they turned Republican in 2020.

By the same analysis, we see that a large state like Texas, which is touted by some as a ‘toss-up’, is in fact stoutly Republican. So, the conclusion, from the pollsters’ own demonstrated inconsistencies in key states, is a higher probability for a Trump victory. This forecast is depicted graphically below, using a simulator from Realcearpolitics.com (Colorado is left Democrat, since it has the lowest probability on our list of flipping red).

Numerically, Trump wins 324 seats, and Biden 214.

(All election data from Realclearpoltics.com, Fivethirtyeight.com, 270towin.com)

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest