Books

Book Review: Jeffery Long Presents A Thorough And Vivid Description Of Hinduism In America

Aravindan Neelakandan

Sep 11, 2020, 03:49 PM | Updated 03:49 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Hinduism in America: A Convergence of Worlds. Jeffery D. Long. Bloomsbury Academic. Pages 304. Rs 1,026.

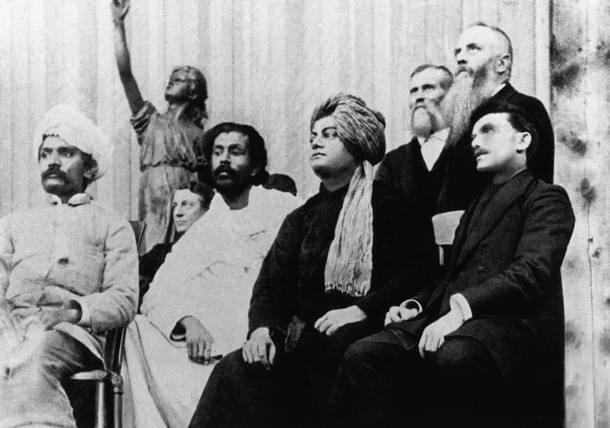

11 September 1893 marks an important date in the history of humanity. On that Monday, an unknown young Hindu monk spoke the words ‘Sisters and Brothers of America’ and with those words brought the universal brotherhood of Hindu Dharma to the United States.

In 2020, 127 years after that declaration of universal brotherhood of all humanity by Swami Vivekananda, Hinduism in America – a Convergence of Worlds, a book by Jeffery D. Long, Professor of Religion and Asian Studies at Elizabethtown College, in Pennsylvania, explores where do things stand with respect to Hindu Dharma in the United States.

The present book is more structured like a textbook though is not one. It takes a historic overview of how Hindu Dharma first came to the United States as a strong influence, right from the transcendentalists to the counter-culture and Guru phenomenon to the present day challenges.

Each chapter comes with a summary and outline in the beginning and a set of study questions as well as a list of suggested books for further reading in the end. This structure makes the book a comprehensive guide for deeper exploration into the subject for those interested.

Of particular interest is the chapter 3 titled ‘'Hinduism Invades America': the Early Twentieth Century’.

For an Indian Hindu, this chapter shows the kind of asymmetry which Hinduism faced in the global context during the colonial centuries.

For us, the usual picture is that of Vivekananda establishing the greatness of Hinduism to an American audience hitherto ignorant about Hinduism and then conducting successful tours.

The picture is true in its own way but that was only the beginning. The Hindu community was already there even before the arrival of Hindu gurus. They had mostly come as indentured labourers. They faced problems of racism in the US.

Was there also anti-Semitism-like hatred towards Hindus and Hinduism? It is interesting to note that the ‘South Asian’ scholars whom Prof. Long quotes do not seem to worry about this. Rather, here, the related research seems to be oblivious to the religious dimension in a strategic manner.

Prof. Long gives the instance of one Hindu spiritual teacher - A.K. Mozumdar who lost ‘his American citizenship in 1923, and eventually, to the Asian Exclusion Act.’ But pointing out Mozumdar’s worshipful nature towards Jesus Prof. Long writes that it was more because Mozumdar was an Indian than because of his religion that he was sent out. But the author does not miss out how racism and Christian anti-Hindu bigotry mutually reinforced each other. And that is why the book is important because it gently prods into the subject – not rhetorically nor forcefully but definitely in a way that points out the connection and leaves it at that:

A number of court decisions early in the twentieth century bear out the conclusion that not only religious anxiety but also racism underlay negative American reactions to Hindus and Hinduism. … American Anti-Asian sentiment—a sentiment which was directed at Chinese and Japanese people, as well as at Indians, or “Hindoos”—culminated in the passing of the Asian Exclusion Act, which stopped the flow of Indian immigration (including that of Hindu monks and other spiritual teachers) until this Act was overturned by another act of Congress in 1965.Long, Jeffery D., Hinduism in America (p. 193). Bloomsbury Publishing. 2020 Kindle Edition.

This aspect is also brought out even more forcefully in the case of Berkeley Vedanta Society. This case played out during the time of Swami Ashokananda (1893-1969).

The case was taken to a court hearing in which contemporary American hatred against Hinduism was in full bloom with all its racist plumage in display.

That particular court hearing, explained in detail by Sister Gargi (Marie Louis Burke 1912-2004) in her book A heart poured out : a story of Swami Ashokananda (Kalpa Tree Press, 2003, pp.238-245), is also a testimony to the resilience of democracy in the US against racism and the religious bigotry in American society.

One wishes the inclusion of this crucial milestone in the history of Hindu Dharma in the US in future editions of Prof. Long's book. Diaspora Hindus too should make it a point to teach this case as a lesson in understanding and combating the deep-rooted prejudices against them, which often take new forms and labels these days but contain the same old hate-content.

The approach of Prof. Long is both historical and multi-dimensional. In the discussion on the Guru phenomenon, the problem of abuse by self-styled 'gurus' figures a lot. From the beginning it has been one of the favoured sticks to beat Hindu spiritual movements with.

In dealing with this aspect Dr. Long asks:

The #MeToo movement has recently shown, quite dramatically, that men in positions of power in a wide range of fields—education, entertainment, business, and politics, and many others as well—take advantage of this power and abuse those whom they see as powerless with a frequency that has, upon being exposed, greatly shaken the public’s perceptions of and confidence in figures who would at one time been viewed with great respect. Why should the field of religion be different than any other in this regard? Indeed, given the pervasiveness of the abuse that #MeToo has revealed, one could well conclude that the question to ask is not “Why have so many gurus been accused of abuse?,” but rather, “Why have more gurus not been accused of abuse?”(p. 232)

Prof. Long is careful enough to point out that this is not an apologist argument for the potential abuse. Through the words of 'a monastic practitioner in a Hindu lineage in America' he points out the following:

The moment ego comes in, we have failed in our mission. We must remind ourselves of that constantly. “I am but thy instrument.” A teacher who forgets this will fall.

In this connection, one remembers Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa who not only encouraged his disciples to always test the Guru ‘like a goldsmith tests the jewel for its gold content’ but appreciated when he found them observing his behaviour closely.

The book deals both with Hindu influences on American popular culture (like in Star Wars and Matrix and in Indiana Jones negatively) as well as the way Hindus are depicted in American popular culture.

Such a study has been long overdue. Dr. Long presents an analysis of the Hindu characters in popular media: Apu in Simpsons, Rajesh in the The Big Bang Theory and Mindy Kaling (Vera Mindy Chokalingam) in The Office (originally a BBC series):

Apu is frequently depicted as being engaged in dishonest business practices—like leaving the hot dogs that he sells in his store out too long—and as generally unscrupulous. ... The identification of Indianness with nerdishness in Raj’s character marks a shift in stereotypes of Indian Americans, from owners of motels and convenience stores, along the lines of Apu, to engineers, scientists, doctors, IT professionals, and so on. … The character of Kelly does not hide from or in any way seek to downplay her Indianness. But her Indianness is not her dominant characteristic as a human being. Her character is flirtatious, competitive, and highly, highly, highly talkative: characteristics that could be possessed by any person, of any culture. Kelly is, in other words, a human being, who happens to be an Indian American Hindu.(pp. 332-333)

This is actually a worrisome development. Hindus being perceived as selfish, unethical and money-minded on the one side and nerdy, intelligent etc., on the other is exactly how Jews were (and are still in some influential quarters) stereotyped in pre-holocaust Christendom.

Are Hindus replacing Jews as the favourite hate objects of Christendom or sharing the hate-space along with the Jews?

The book also explains the way Hindutva is used as a contemptuous label to attack any Hindu activism in the United States. Early in the book itself Prof. Long tries to differentiate between Hindutva and Sanatana Dharma thus:

The original use of this term to refer to an ethnicity and a nationality continues to shade its meaning today. The Hindu nationalist political movement, which identifies Hinduness—or Hindutva—with Indianness, works with this understanding. The Hindu nationalist political movement, which identifies Hinduness—or Hindutva—with Indianness, works with this understanding.... The term Sanatana Dharma, by way of contrast, has the connotation of an eternal dharma: an eternal order or way of life, with no beginning or final end point in time. It also has connotations of universality. For Hindu universalists, Sanatana Dharma conveys the idea of a religion with no boundaries, or of a deeper philosophy undergirding and encompassing all religions(p. 59).

To the present reviewer, this differentiation, however well-intentioned, is problematic.

'Hindutva' was the term used by Rabindranath Tagore at least a decade before Veer Savarkar. Savarkar himself was an anti-racist way ahead of his time, claiming universal humanity as the only reality and calling out all claims of race and racial purity as fiction. His Hindutva was anchored to the sacredness of, and rootedness to, India. Yet, a narrative has been successful in projecting Hindutva as a kind of Indian version of racist rightwing politics.

Prof. Long states that Hindutva identifies Hinduness with Indianness – which is true but not in the exclusivist sense. For example, while Islamist politics does not even accept Ahmadiyas as Muslims, Hindutva accepts Muslim patriots like Ashfaqullah Khan, Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam etc. as Hindus without demanding any theological compromises from them.

Savarkar himself stated that at the height of one’s Hinduness one ceases to be a Hindu and embraces all universe as his or her home. Now that is as universal as it can get.

In chapter eight, ‘Identity and Engagement’, he takes up the same issue in the context of Hindu American Foundation (HAF). He quotes quite a few responses of HAF members and volunteers with regard to the problem of them getting labelled as followers of Hindutva. One of the respondents explains:

Those who took the initial lead to support and speak for Hindus happened to include members of the RSS and the VHP and given the fact that those two organizations had already been demonized in India by a whole host of Indian political and religious groups, it was easy to label Hindu activists here as Hindutva activists.HAF respondent quoted by Long, Jeffery D. (p. 348)

One can call this Siddhartha-Hamsa Nyaya. The one who cares for Hindu Dharma and Hindus when they are attacked and hurt naturally has a right to speak for them.

Prof. Long uses the hostile response of a significant section of Hindus to ‘Not cast in caste’ report of HAF to drive home the point that it is neither pro-Left as claimed by its Hindu critics nor Hindutva as its Left-haters love to label it:

The HAF report on caste—Hinduism: Not Cast in Caste—released in 2011, evoked quite a considerable backlash from many Hindus who saw it as an attack on Hinduism and who argued that HAF was a front group for anti-Hindu forces in the United States—an ironic charge when one takes into account allegations from the other end of the political spectrum that HAF is a front for Hindu nationalism, due to its involvement in the school textbook issue. The brief on homosexuality, issued more recently, provoked much less backlash, although the issue of gay rights had emerged as a major dividing line in the Indian context.(p. 349)

If one goes through the endorsements of the HAF report, one will find prominently featured the message of Swami Dayananda Saraswati as the Hindu Dharma Acharya Sabha (HDAS) which states the following:

Birth-based discrimination and cruel treatment of individuals and families which developed in Hindu society over time as socially sanctioned practices are in gross violation of ancient Hindu teachings and philosophy. ...HDAS is aware that what started as rural kinship, creating a sense of security and identity in communities, developed over the centuries into entrenched social practices, particularly in deep rural areas. Consequently, complete elimination of such practices will take time. Therefore, concerted, sustained and proactive action at the grass roots is required to rid our society of these birth-based unfair discriminations.

Swami Dayananda Saraswati was also then the head of Dharma Rakshna Samiti (DRS), an organisation closely aligned with the RSS. The opposition to the HAF came more from the traditionalists, for traditionalist reasons and not from the Hindutva side.

In fact, long before HAF, a similar undertaking had been taken by the VHP. Functionally, traditionalists and Hindutvaites are overlapping circles but yet they have crucial areas which lie outside intersecting circles.

Prof. Long writes that ‘the issue of gay rights had emerged as a major dividing line in the Indian context.’ In reality, the Hindutva organisations were conspicuous by their non-opposition when the Indian Supreme Court decriminalised homosexuality.

Again, there have been individual voices for and against homosexuality but the Hindutva movement in India set an example for the religious movements in the world as to how to respond or keep silent about individual sex preferences.

So, many of the instances which Prof. Long sets out as differentiating between Hindutva and Hindu Dharma organisations actually seek revising one’s negative stand on Hindutva and abandoning the artificial Hindutva-Hindu Dharma binary.

One important aspect of the book is the caution that it gives to Hindus in the conclusion. The prejudices against the Hindus are not going to go. They are too deep-seated. Hindus have a tough path before them. They should not fall into the wrong comforts of believing the American Right-Wing just because of the Hindu-phobic nature and hypocrisy of the Left.

At the same time, one also needs to caution even sympathetic Hindu academics against falling to the charm of the Leftist-fashion statements of the groups like Sadhana Coalition which even goes against restoration of gay-rights and the rights of Dalits in Jammu and Kashmir.

The talisman for Hindus can then be rightly the words of Swami Vivekananda with which Prof. Long ends his book:

This freedom that distinguishes us from mere machines is what we are all striving for. To be more free is the goal of all our efforts, for only in perfect freedom can there be perfection.

On the whole, the book is important as it deals with the Hindu phenomenon in the United States in a comprehensive and positive way, covering almost all dimensions and presenting a clear picture of the American Hindu realm. The book is a must for every Hindu library both in India and abroad, and also for Diaspora Hindus.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.