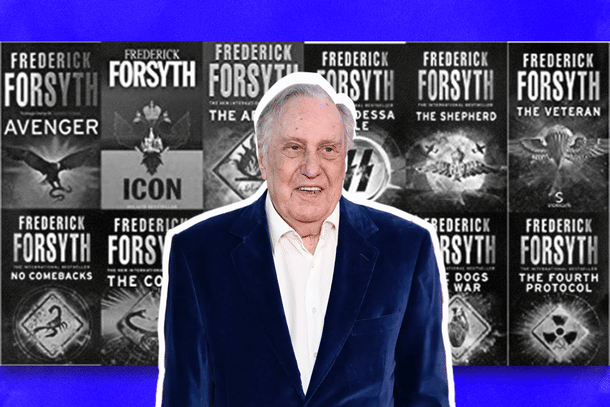

Books

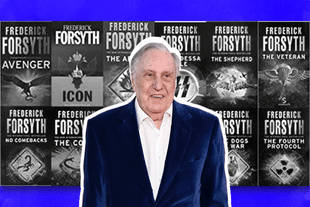

Frederick Forsyth (1938-2025): Master Architect Of 'Faction'

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jun 11, 2025, 03:02 PM | Updated 03:01 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

With the passing of Frederick Forsyth on 9 June, 2025, the final dossier on a master of the political thriller has been closed. A former RAF pilot who became a journalist with Reuters and the BBC before turning to political fiction, he was uniquely placed to understand the workings of power—and he channelled that insight into the genre he made his own: 'faction.'

His work occupied the liminal space between lesser-known pages of documented history and enchanting story telling. The pages of his fiction took you into a world so realistic that they look like leaked intelligence.

An author who served as a cartographer of the unseen yet very real world, mapping the deep and often unsettling forces that shaped the mid-twentieth to early twenty-first century, he leaves behind a legacy that blends entertainment, political education, and, at times, propaganda.

From his explosive 1971 debut, The Day of the Jackal, Forsyth established a formula that would captivate readers for decades. His protagonists are rarely flamboyant super-spies in the vein of James Bond. Instead, they are often professionals – soldiers, mercenaries, assassins, or intelligence operatives – defined by their expertise, meticulous planning, and cool-headed execution of their tasks.

The drama in a Forsyth novel unfolds not through improbable gadgets or over-the-top action sequences, but through the detailed, almost documentary-style, exposition of procedure. Whether it is the painstaking process of acquiring a false identity in The Day of the Jackal, the mechanics of a coup d'état in The Dogs of War, or the intricate plot to smuggle a nuclear device in The Fourth Protocol, Forsyth's commitment to technical accuracy is legendary. This dedication to realism lends his narratives a chilling plausibility that few in the genre could match.

His prose was lean and reportorial, a direct inheritance from his journalistic background. That would have been a handicap for most fiction writers then. But his typewriter keys transformed that verily into his unique strength. He eschewed florid language in favour of a direct, almost clinical, narration that served to heighten the tension. This, combined with his masterful control of pacing, creates a relentless sense of suspense. The reader is drawn into a world of high-level government meetings, clandestine operations, and moral ambiguity, where the fate of nations can hinge on a single, well-executed, plan or a fatal miscalculation.

A recurring theme in his novels is the power of the individual. His novels often feature a lone protagonist or a small, dedicated team operating in the shadows, battling against, or, navigating vast, impersonal state apparatuses.

Was there a bitter sense of cynicism towards established institutions, be it government bureaucracies or intelligence agencies? Most probably. This focus on the individual also allows Forsyth to explore the moral complexities of his characters' actions.

It was in The Odessa File that Forsyth crystallised an ethical principle that has served as my own moral compass. With sharp clarity, he drew a line between national contrition and individual culpability. The novel’s quiet insistence is that while a nation must reform the culture of hatred that permitted such crimes as the Holocaust, the individuals who perpetrated them must never be allowed to find anonymity within the collective. For it is in that shadow of shared blame that true monsters lie in wait, ready to inject their old poison back into the soul of a society.

The novel's protagonist, Peter Miller, a freelance reporter in Hamburg in 1963, comes into possession of the diary of a deceased Jewish Holocaust survivor. The diary details the unspeakable horrors witnessed in the Riga Ghetto, ruled by the sadistic SS Captain Eduard Roschmann, known as the "Butcher of Riga." Haunted by the account, Miller begins a personal quest to hunt down Roschmann, who he discovers is not only alive but is being shielded by a powerful, clandestine organization.

Miller’s investigation leads him to "ODESSA" (an acronym for Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen, or Organization of Former SS Members). In Forsyth's narrative, ODESSA is a highly efficient, well-funded secret society dedicated to smuggling Nazi war criminals to safety and, more chillingly, working to establish a new, pro-Nazi state in Egypt that would threaten Israel with biological and radiological weapons.

Miller goes undercover, penetrating the secretive organisation in a tense, high-stakes game of cat and mouse that pits him against ruthless former Nazis who will stop at nothing to protect their new lives and dark ambitions.

Here are the facts which are today available literally on our fingertips and we can evaluate how closely they mirror the narrative presented in the fiction.

ODESSA: While Forsyth portrays ODESSA as a single, monolithic global conspiracy, the historical reality was more fragmented. The term was used by Allied intelligence to describe a number of separate, often uncoordinated, escape networks and ratlines. These routes, often running through Austria to Italy and then to South America or the Middle East, were instrumental in helping notorious Nazis like Adolf Eichmann and Josef Mengele evade justice. So, while the centralised, spider-web-like organisation of the novel is a fictional creation for narrative effect, the existence of powerful networks that helped Nazis escape was terrifyingly real.

Eduard Roschmann: The so-called ‘The Butcher of Riga’: The novel's antagonist was a very real and brutal historical figure. Though a few historians contest his cruel portrayal, most agree that he was indeed a ruthless murderer. Roschmann was indeed the commandant of the Riga Ghetto in Latvia, responsible for countless atrocities and murders. After the war, he escaped from a detention camp and, with the help of a Catholic bishop, fled via the ratlines to Genoa and then to Argentina in 1948, where he lived under a false name.

Nasser-Nazi Links: For an Indian who grew up in Nehruvian India, Egyptian leader Nasser was the personification of anti-imperialism and the hero of Non-Aligned Movement. But the way he was shown in the novel was a rude shock. He was collaborating with the ex-Nazis to destroy Israel with radiological and biological weapons. Was this propaganda or fact?

In reality, there is no hard evidence to show that Gamal Abdel Nasser was planning to use biological weapons against Israel as the novel claimed.

Although, there was indeed a collaboration between the Germans and the Egyptians over a weapons project under Nasser.

Factory 333

At the heart of this collaboration was a desert complex known as Factory 333. From 333’s workrooms missiles were getting churned out even as West Asia was on constant boil and on a trajectory towards a war on Israel.

The project was indeed led by a team of prominent German scientists:

—Wolfgang Pilz, a key propulsion expert who had worked on the V-2 at the Peenemunde army research centre and later for the French government, became the technical director of the Egyptian program.

—Paul Goercke and Hans Kleinwachter, who were both specialists in electronic guidance systems, also worked in the site.

—A visiting scientist from Germany was Dr Eugen Sanger. He was a renowned aerospace engineer who provided crucial early consultation that helped launch the program.

Apart from them there was a team of approximately 200 German technicians set out to develop a series of liquid-fuelled ballistic missiles for Egypt. A few such missiles were 230-mile El-Zafir (Victory) types, and the 370-mile El-Kahir (Conqueror). Nasser boasted that these missiles could strike any target "south of Beirut," a clear and direct threat to every major city in Israel.

Israel soon launched its 'Operation Damocles' which led to the individual assassinations of key German technologists involved in the project which led to the collapse of Factory 333.

The German-Egyptian collaboration also extended beyond rocketry and included former Nazis.

Leopold Gleim was a high-ranking SS-Standartenfuhrer, a former Gestapo chief in Poland during the occupation and he was the man directly involved in the brutal suppression of the Polish population. After the war he converted to Islam, went to Egypt and as Lt. Col. Al-Nasher established the new state security apparatus, effectively teaching the Nazi methodologies to Egyptians.

Alois Brunner, who was one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, directly responsible for the deportation of over 1,00,000 Jews from Austria, Greece, France, and Slovakia to the death camps, escaped to Egypt with ‘Red Cross’ papers and then became a consultant for Egypt and then Syria in intelligence operations.

Those were just two of the many Nazi war criminals employed by Nasser’s Egypt and his allies.

Nasser's government also sought to create with the help of Nazi propaganda-specialists, a powerful anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic propaganda campaign aimed at both the Arab world and international audiences.

Johann von Leers, a professor and one of the most fervent anti-Semitic propagandists of the Third Reich, had written over two dozen books for the Nazi party. After the war he escaped to Egypt, converted to Islam, changing his name to Omar Amin, and served as a high-level political advisor in the Ministry of National Guidance, spearheading anti-Israel propaganda.

Louis Heiden, another Nazi propagandist also escaped to Egypt, converted to Islam, became Louis Al-Hadj, and served as a high official in Nasser's anti-Jewish propaganda cell. He also translated Hitler’s Mein Kampf into Arabic.

Hans Appler, who became Salah Shafar, was a close associate of Goebbels. Franz Bartel who became El Hussein was a former Gestapo officer. Both were employed in the ‘Jewish Departments’ of Egypt's propaganda and information services.

Willi Berner who became Ben Kashir was an SS officer at the Mauthausen concentration camp. He was employed, along with other former SS men, to train volunteers for the Palestine Liberation Army (PLA).

Now all this is information easily available through Google search. But back in 1972, there was no internet. No email. Even then, Forsyth could put into his fiction indicators towards all these. Even in this age of Google search, Forsyth's 'Faction' is relevant as to what to search for. It was eye-opening to anyone who was blind to the anti-Semitism that was at the heart of the Palestinian movement.

Impact of the Novel

The novel's immense popularity and its vivid portrayal of Eduard Roschmann brought his name out of obscure historical records and into the global spotlight. Living under the name "Federico Wegener" in Argentina, Roschmann was exposed.

In 1976, the West German government requested his extradition. Alerted and fearing capture, Roschmann fled from Argentina to Paraguay, where he died in a hospital in Asunción in August 1977, a fugitive to the very end.

It is widely acknowledged that Forsyth's novel was directly responsible for flushing this real-life monster out of hiding.

'The Afghan' Controversy

Published in 2006, The Afghan saw Forsyth return to the world of post-9/11 counter-terrorism. The plot involves a retired British army officer, Colonel Mike Martin, who bears a striking resemblance to a captured Taliban commander.

Martin is sent undercover into the heart of Al-Qaeda to uncover details of a catastrophic impending attack. The novel, in typical Forsyth fashion, is replete with technical details about intelligence gathering, terrorist networks, and military operations.

However, it was a specific part of the novel that ignited a significant controversy in Kerala. In the book, Forsyth introduces two Keralite youths, who were radicalised Islamist terrorists, and then includes the following passage:

Captain Montalban knew vaguely that most of India is Hindu but he had no idea that there are also a hundred and fifty million Muslims. He was not aware that the radicalization of Indian Muslims has been just as vigorous as in Pakistan, or that Kerala, once the hotbed of Communism, has been particularly receptive territory for Islamist extremism.

This characterisation was met with widespread criticism from the usual group of intellectuals, writers, and even a few officials in Kerala. They cried that Forsyth's portrayal was a gross misrepresentation and an injustice to Kerala.

But what was the truth?

Right from the 1998 Coimbatore bomb blast to the 2003 Marad massacre of Hindus, the claw marks of radical Islamism from Kerala were too explicit to ignore.

Just two years after the publication of the novel, Praveen Swami, a journalist covering national security matters and writing for the The Hindu reported militant networks in Kerala. (‘The Lashkar-e-Taiba’s Army in India,’ The Hindu, January 17, 2009). In other words, facts proved that Forsyth’s grasp of Kerala's reality was far better than those of the Malayali intellectuals who criticised him.

The genius of Forsyth was not just in the meticulous architecture of his plots, and the almost-superhuman hard work he put forth in collecting facts but in his unwavering conviction that fiction could be the most potent vehicle for uncomfortable truths.

Whether detailing the mechanics of an assassination, the flight of a war criminal, or the strategic ambitions of a nation, he compelled us to look beyond the headlines, to understand that the hidden machinery of history is often more relentless and more incredible than any fiction.

He armed his readers not with fantasy, but with a new, more discerning lens to view the world through, leaving behind a body of work that will long stand as a testament to the enduring power of 'faction' in revealing fact. In all that, he also upheld the power of the individual human action and human values.