Culture

A Closer Look at the Ties Between Indians and African-Americans

Kaajal Ahuja

Jan 25, 2015, 01:55 AM | Updated Feb 12, 2016, 05:18 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Indian-American story is an impressive one. The 3.3 million strong Indian American community has thrived in it’s adopted homeland with among the highest income levels in the country as well as many accomplishments in fields ranging from medicine and academia to entrepreneurship and technology. Although Indian Americans have always overwhelmingly voted Democratic, they have never had it so good in government as in the past 6 years in President Barack Obama’s administration. At least 30 Indian Americans have been appointed to senior positions in the Obama administration. With all the doors within government that President Obama has opened to Indian Americans, it seems fitting that he become the very first US President to preside over the annual Indian Republic Day parade during his upcoming 3 day visit to India.

As an educator and historian who’s been researching the ties between India and African Americans, I know that there is very little knowledge of the extent and depth of these relationships among Indians. These ties should not interest history buffs alone. A lack of knowledge creates a vacuum that allows misinformation to thrive. I had a taste of one such fallacy at a recent dinner in Washington DC. The chatter among the mostly Indian-American crowd revolved around President Obama’s impending India trip. Most of the desis expressed pleasure at the progress made in Indo-US relations since Prime Minister Modi’s election and the turnaround in diplomatic ties from the lows reached during the Khobragade affair. We applauded the firm stand that India took against American diplomat Wayne May and his wife Alice Muller May who were expelled for their disparaging remarks on India made on Facebook (here).

The disdain and contempt toward India among some State Department staffers and the junior diplomatic corps is not terribly surprising to DC locals who frequently run into these attitudes in this city. Paradoxically, US embassies in the third world often attract employees who harbor parochial views of their host countries yet accept such postings because of the handsome and “above pay grade” perks that come with them. Our conversation drifted to the new US Ambassador to India – Indian American Richard (Rahul) Verma. Would his presence improve the tone in the rank and file, back offices and inner sanctum of the US Embassy in India? We wondered.

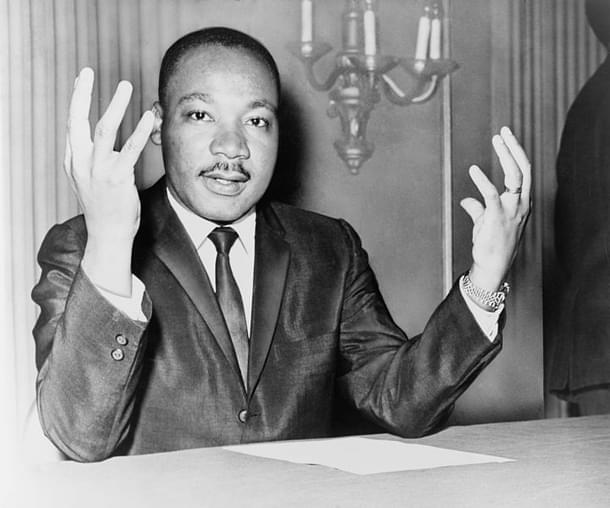

“Oh, but nobody is as racist as us Indians” one Indian woman remarked, “we’re obsessed with fairskin and completely ignore Blacks in India”. Such statements, usually betray racist attitudes that Indians have experienced and internalized. They also fly in the face of history that shows many ties and friendships between Indians and African Americans. For wasn’t it Martin Luther King Jr. who exclaimed upon his travels within India in 1959 that:

“virtually every door was open to us. We had hundreds of invitations that the limited time did not allow us to accept. We were looked upon as brothers with the color of our skins as something of an asset”.

Excessive mea culpa by some Indians is a way to find an acceptable spot in the highly complex racial landscape of America. One would be hard pressed to ever hear a White person declare, even after a Ferguson type event (here), that there is none so racist as the European or European-American. Nonetheless, there is no denying the fetish that many Indians have for fair skin. As I tried to explain, this preference, usually an aesthetic one for a fair skin tone is “colorism” rather than racism.

In cases of colorism, people of the same race though with different skin tones, will be treated differently. The preference for “fair and lovely” in Indian matrimonial ads reflects this bias. Racist attitudes on the other hand can be evident toward all people of a certain race, even if they have different skin tones. African-Americans come in many shades of brown but are usually subject to similar racist attitudes across the color spectrum by perpetrators. Colorism, is a problem among not only Indians but also African Americans, Latinos and South East Asians. It has its roots in class structures both before and after colonialism when a lighter skin brought privileges and greater social mobility.

Are there racist Indians? Of course. But the “there is nobody as racist as us Indians” narrative finds currency precisely because of our poor historical knowledge. It has also been seeded and nurtured to create a fertile ground for “breaking India” activities. It is even more worrying when Indian American US government employees blithely repeat these assertions. In their remarkable book, Breaking India: Western Interventions in Dravidian and Dalit Faultlines, authors Rajiv Malhotra and Aravindan Neelakandan have drawn our attention to the role played by US and European churches, academics, think-tanks and human rights groups in superimposing the history of American racism and Black/White relations onto Indian society.

As they caution us, the “Afro-Dalit” project being orchestrated by such institutions attempts to cast Dalits in India as India’s “Blacks”, a different race altogether (even though several scholars and archaeologists and geneticists debunk this idea) from their oppressors – the “upper” castes. These activities are seeking to create permanent fissures in Indian society. “Nobody is as racist as us Indians” often devolves to “Hinduism is racist” and sets the stage for all sorts of interventions into India from sanctions to massive conversion drives.

In my own research, I’ve found that African Americans and Indians have shared deep affection, friendships, journeys to and fro, long correspondences and many other linkages cemented by common histories of colonialism, racism and imperialism. These linkages were driven on the one hand by African Americans looking to find allies among people of color world over in their fight for civil rights and on the other by Indians looking for international support for the Indian freedom movement.

Indians are usually aware of the influence of Gandhian principles on civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. However few realize that King himself had never met Gandhi. He visited India for the first time in 1959, a decade after Gandhi’s death. He had been introduced to the principles of satyagraha and ahimsa by his mentors and teachers – Howard Thurman and Benjamin Mays – both leading lights of the Black intellectual movement of the 20th century who sojourned to India and met Gandhi and other Indians. Thurman, in 1935 became the first African-American to have met Gandhi. It was upon meeting Thurman that Gandhi famously remarked:

“it may be through African-Americans that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world”.

Benjamin Mays went on to becoming the President of Morehouse College, the all male, Black college in Atlanta which MLK Jr. attended and remained a mentor to King throughout his life.

Other African-American luminaries who came to India include Mordecai Johnson, the President of Howard University, Bayard Rustin, the famous leader of social movements in civil rights, gay rights and pacifism and more recently, Jesse Jackson. There have been numerous cultural connections too. Oprah Winfrey of course but also Alice Coltrane, the musician wife of of the famous saxophonist John Coltrane who then founded the Vedantic Center, an ashram in California. Singer, actor and civil rights activist Paul Robeson found common cause with musician Bhupen Hazarika, who later with his friend’s blessings adapted Robeson’s famous “Ol Man River” to the Assamese “Bistirno Parore”.

Indo-African American links were also forged by Indians who travelled to the United States. These Indian nationalists – Swami Vivekananda, Lala Lajpat Rai, Rabindranath Tagore, Sarojini Naidu, Kamala Chattopadhyaya – travelled to the US to influence public opinion there in favor of the Indian freedom struggle. In their efforts toward gaining international sympathy for the plight of Indians under colonial rule, they found many sympathizers and friends among Black leaders.

Writer Nico Slate, in his book “Colored Cosmopolitanism, The Shared Struggle For Freedom in the United States and India” points to the sense of “colored solidarity” that many Indians and African Americans expressed and acted upon. He recounts in the book the experience of Kamala Chattopadhyaya, the Indian social reformer and freedom fighter who on her visit to the United States in 1941, was asked to move from the “whites only” section of a segregated train. Refusing to do so and in response to the ticket collector’s query about where she was from, Kamaladevi replied:

“It makes no difference. I am a colored woman obviously and it is unnecessary for you to disturb me for I have no intention of moving from here”.

Another Indian nationalist, Lala Lajpat Rai, lived in the US from 1914 to 1919, a period of 5 years. During this time he made many connections including those with George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B Dubois and the founders of the NAACP. It was W.E.B DuBois who had remarked that “we American Negroes are the bound colony of the United States just as India is of England.” DuBois remained a loyal friend of Rai and as the founder of The Crisis, the official organ of the NAACP (National Association of the Advancement of Colored People) provided valuable press and coverage in the United States to Indian nationalist goals.

In his book “TheUnited States of America: A Hindu’s Impressions and a Study”, Rai in turn wrote extensively on African-Americans in chapters titled “Caste in America”, “The Education of the Negro” and “ The Negro in American Politics”. He spoke movingly about the plight of the African American community in the Jim Crow era:

“Legal distinctions and discriminations are mostly confined to the South, but race prejudice is to be found practically throughout the United States. Negroes are excluded from hotels, Young Women’s Christian Associations, Young Men’s Christian Associations, theatres, saloons and are even refused interment in white cemeteries in some cases in direct violation of local laws. In the absence of legal regulations, public sentiment results in the Negro attending separate churches and registering at separate hotels, confines him to special seats in the theatres, segregates him in cities and even in country places and tends to keep him apart from white people in all relations of life. The Negro is the pariah of the US”.

In the book, End of Empires: African Americans and India, author Gerald Horne brings attention to the Ahmadiyya movement that originated in Punjab in 1890 and sent its missionaries to the US. The movement mostly found currency among African Americans. Horne remarks that the Ahmadis made “a scorching critique of Christianity with a searing analysis of the plight of Black America”.

He quotes from an Ahmadiyya journal which ran a story in 1922 about the “thirty lynchings of Negroes by white Christians”…..”some were burnt at the stake, others were put to death”. Other Indians who made long trips to the US and commented and wrote extensively about what they saw and experienced were Rabindranath Tagore and Swami Vivekananda. Swami Vivekananda’s trip to the United States in 1893 is best known for his speech at the World Parliament of Religions.

However during this time he travelled throughout the US and shared and wrote about his many observations about race and class in America including the racial insults he received there. He was often referred to as a colored man, a description he relished and saw African-Americans as his “brothers”. In a write-up by a reporter of the Saginaw Courier-Herald on March 22, 1894, Swami Vivekananda was quoted to have remarked on “the condition of the Negro in the South who is not allowed in hotels nor to ride in the same cars with white men, and is a being to whom no decent man will speak”.

President Obama’s India trip happens to come on the eve of Black History Month, celebrated every February in the United States. The President’s huge popularity among Indians should also belie the charges of antipathy between Indians and Blacks that are made inadvertently but sometimes maliciously. Our first Black President’s trip to India seems an opportune time to put the spotlight on ties – “the bonds of fraternity”, in Martin Luther King Jr.’s words – that have existed and continued between Indians and African Americans.

Kaajal Ahuja is an educator and historian. She is the founder of an education company focused on Indian history. She lives in Washington DC.