Culture

The Etymology Of Kashmir: Setting The Record Straight

Nityanand Misra

Apr 02, 2017, 05:53 PM | Updated 05:53 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The etymology of the word ‘Kashmir’ has been a topic of conjecture for centuries in popular writings and narratives. Right from Mughal ruler Babur in the sixteenth century to H H Wilson and Ralph T H Griffith in the nineteenth century and to modern writers today, various hypotheses have been made about how the name, Kashmir, is derived. The conjectured etymologies are widely read. The Wikipedia article on Kashmir gets more than 2,500 views every day and had more than 1.25 million views in 2016. As of today, it carries several popular but incorrect etymologies. This article is an attempt to show why these popular etymologies are incorrect and to set the record straight by stating the etymology of the Sanskrit word kashmira as per authoritative Sanskrit works. The meaning associated with this etymology is also briefly discussed.

Five Hundred Years Of Guesswork

Nearly five centuries ago, the Mughal invader and conquerer Babur made the wild conjecture that Kashmir got its name from a race of men called Kas. Horace Hayman Wilson, the English Orientalist, who compiled the first Sanskrit-English dictionary in 1819, conjectured that the name Kashmir came from Kashuf-mir, Kashuf being the Muslim name of the Hindu sage Kashyapa. So much credence was given to this guess that the English cricketer and traveller Godfrey Vigne wrote in 1842 that Wilson’s etymology was “no doubt, the immediate derivation of the name.”

Vigne came up with another guess, citing the opinion of G C Renouard (the then secretary of the Royal Geographical Society of London), that Kashmir was derived from the Hindu name Kashyapa-pura, which became Kasha-mur and eventually Kashmir. To support this guess, Vigne even gave a “scientific” reason that the letters ‘p’ and ‘m’ are commutable. Following Wilson, Griffith too wrote in his 1870 translation of Valmiki Ramayana that the name Kashmir came from Kashyapa-mira, which meant “Kashyap’s lake”. In 1879, William Wakefield repeated both these etymologies and also cited a third, one he called Vigne’s “ingenious theory”, which traced the name Kashmir to the biblical figure Cush.

Perhaps inspired by the nirukti in the Nilamata Purana, another etymology came up which said that Kashmir, which meant “desiccated from water”, derived from the Sanskrit ‘ka’ meaning “water” and ‘shmir’ or ‘shimeer’ meaning “to desiccate”. This etymology is published in hundreds (or maybe thousands) of books. The Wikipedia article on Kashmir calls this a “popular local etymology”. Unsure of whether to believe it or not, Christopher Snedden writes in the 2015 book Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris that the name Kashmir “may come from a Kashmiri or Sanskrit term that means ‘to dry up water’”.

Why They Are All Wrong

The Sanskrit word for Kashmir is simply kashmira (kasmira/कश्मीर). This is how the region is referred to in numerous Sanskrit works including the Mahabhashya of Patanjali. In addition, Sanskrit has several derivative words from kashmira. The very first is kashmira (kasmira/काश्मीर) which involves a vowel change (the first vowel is elongated) and means “belonging to Kashmir” (as in saffron, grapes, or a person from Kashmir). The feminine form is kashmiri (kasmiri/काश्मीरी) which is used in the Mahabharata. Other words include kashmiraka (kasmiraka/काश्मीरक) which means “a person from Kashmir”and kashmira-mandala (kasmira-mandala/काश्मीर-मण्डल) which means “the region of Kashmir” – both are used in the Mahabharata. The Kashika commentary on rule 4.1.176 of Panini’s Ashtadhyayi lists the word kashmira in a special group for deriving words for female kshatriya descendants.

As the word kashmira and its derivatives are common in Sanskrit literature and mentioned even in grammar works, it is evident that Kashmir it is not the corruption of a Sanskrit name like Kashyapa-pura or Kashyapa-mira but simply comes from the Sanskrit word kashmira as a result of schwa deletion.

As for the “desiccated from water” etymology, which builds on the nirukti, given by the Nilamata Purana, a little scrutiny shows that it is also untenable. All that the Nilamata Purana says is (translation by Ved Kumari): “Prajapati is called ‘ka’, and Kashyapa is also Prajapati. Built by him this region will be called Kashmira. Because water called ‘ka’ was taken out by Balarama (the plough-wielder) from this region, so this will be called Kashmira in this world.”

The verses only explain the initial letter of the word kashmira by connecting it with Prajapati and water, without offering any etymology whatsoever. While one of the meanings of ‘ka’ is indeed “water” in Sanskrit, there is no word resembling shmir or shimeer in Sanskrit which means “dessicated”. The closest root in Sanskrit is shmil (smil/श्मील्) which means “to blink”. For this reason, the “dessicated (=shmir) from water (ka)” etymology is indefensible.

Finally, the etymology given by Babur (referring to a race of men called Kas) and Vigne’s “ingenious theory” (referring to the biblical Cush), they are too far-fetched and fanciful to be taken seriously.

Does A Sanskrit Etymology Even Exist?

Yes. The Sanskrit grammar tradition has a well-documented etymology of the word kashmira, which is nothing like the conjectures proposed over the last 500 years. This etymology comes from the Unadi Sutras, rules which list roots and suffixes for irregular words in Sanskrit. The Unadi Sutras are referenced by Panini, who is dated around 500 BCE by modern scholarship but much earlier by scholars like Rajwade and Satyavrata Samashrami. While some opine that Panini himself authored Unadi Sutras, many others believe it to be an older text. Whatever one thinks of the date of Panini and the authorship of Unadi Sutras, it is certain that from at least around 500 BCE, Sanskrit etymologists and grammarians have had an etymology for the word kashmira.

What Is This Etymology?

Rule 4.32 in the five-part recension of Unadi Sutras reads kashermut cha (kasermut ca/कशेर्मुट्च). Carrying over the suffix ira (ईर/ira) which is introduced in rule 4.30 and stated to be a part of words like sharira (“the body”) and gambhira (“serious, deep”), what the rule means is (translation mine): “[The suffix] ira (ईर/ira) [occurs] after [the root] kash (kas/कश्), and [the letter] ‘m’ also [is added before the suffix].”

This implies the following etymology of kashmira: kash + m + ira = kashmira

(kas + m + ira = kasmira/कश् + म् + ईर = कश्मीर)

All the major commentaries on Unadi Sutras — those by Ujjvala-datta, Shveta-Vanavasi, Mahadeva Vedanti, Perusuri, Narayana Bhattathiri, Bhattoji Dikshita, and Dayananda Sarasvati – give the example of kashmira for this rule and add that this refers to the region (desha) or country (janapada) named kashmira. There is no doubt whatsoever that as per Sanskrit etymologists and grammarians, the name of Kashmir comes from a rule in the Unadi Sutras.

What Does Kashmira Mean As Per This Derivation?

As per the Dhatupatha, the root kash (kas/कश्) has two meanings in Sanskrit – “to go” and “to rule”. The words derived by Unadi Sutras usually denote the subject of the verb, but sometimes they can also denote the object of the verb. Commenting on the aforementioned rule in the Unadi Sutras, Dayananda Sarasvati (1824-1883) writes (translation mine): “kashmira is one who goes or rules, or [it is the name of] a region.”

While this interpretation makes theoretical sense, it does not explain the meaning of kashmira the region. Moreover, the term kashmira in Sanskrit is hardly used in the sense of somebody who goes or rules, and is almost invariably used to refer to the geographical region of Kashmir. Intuitively, the suffix should denote the object of the action “to go” for the word to refer to a region. This is confirmed by Narayana Bhattathiri (1559–1645), who in his commentary on the same rule writes convincingly (translation mine): “[The word] kashmira [means] where people go, [i.e. the name of] a region.”

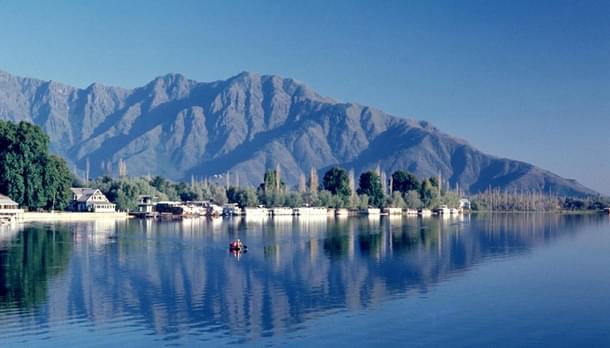

Thus, the Sanskrit word kashmira literally means “a place where people go”, and this can be interpreted as “a place worth going to”. This is not surprising given the natural beauty of Kashmir which has attracted many a traveller since time immemorial. Even in the Mahabhashya, Patanjali gives example sentences where he talks of going to Kashmir and eating rice, the staple food of Kashmir.

Conclusion

In the tradition of Sanskrit grammar, some words are considered avyutpanna, i.e. having no etymology. It may be argued that since words formed from Unadi Sutra-s are considered to be ready-made by Panini, kashmira is really an underived proper noun for which the author of Unadi Sutras traced the most similar-sounding root. The counter-argument is that Panini’s rules apply to derivations and accents of words implied by Unadi Sutras also and historical grammarians like Shakatayana have held the view that all names are derived from roots (i.e. they are vyutpanna and have a specific etymology).

Whatever view one supports, what is certain is that if an etymology of Kashmir from a Sanskrit word or root is to be considered at all, it must be in accordance with Sanskrit etymological and grammatical sources. This is why the popular etymologies proposed by Wilson and Vigne and the “dessicated from water” etymology are to be discarded. They are based on conjecture and involve untenable assumptions of shortening, corruption, and/or commutation in the original Sanskrit name to derive the word Kashmir. The etymology implied by the rule in the Unadi Sutras is a well-thought and structured one which does not suffer from these problems. It makes intuitive sense by suggesting the region is worth going to, derives the name completely without any shortening or commutation, and is supported by a long chain of Sanskrit grammarians for at least 2,500 years. Therefore, the Unadi Sutra etymology is the only one to be favoured.

The author works in the investment banking industry. He is an amateur researcher, editor, and author in the field of Hinduism and Indology. He has edited six books in Hindi and Sanskrit, and has authored the English book ‘Mahaviri: Hanuman-Chalisa Demystified’, which is an expanded and annotated translation of the Mahaviri commentary on the Hanuman Chalisa.