Culture

The Great Goddess Lalita And The Sri Chakra

Subhash Kak

Oct 01, 2016, 02:25 PM | Updated 02:25 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The great Goddess Lalita, also known as Tripurasundari, Maharajni and Rajarajesvari amongst other names, is the presiding deity of the most esoteric yogic practices associated with the Sri Chakra (also called Sri Yantra) that are collectively called Sri Vidya.

According to the Vedic view, reality, which is unitary at the transcendental level, is projected into experience that is characterised by duality and paradox. We thus have duality associated with body and consciousness, being and becoming, greed and altruism, fate and freedom. The gods bridge such duality in the field of imagination and also collectively in society (Kak, 2002): Vishnu is the deity of moral law, whereas Shiva is Universal Consciousness. Conversely, the projection into processes of time and change is through the agency of the Goddess. Consciousness (Purusa) and nature (Prakrti) are opposite sides of the same coin.

The mystery of reality may be seen through the perspectives of language (because at its deepest level it embodies structures of consciousness) and logic (Nyaya), physical categories (Vaisesika), creation at the personal or the psychological level (Sankhya), synthesis of experience ( Yoga), analysis of tradition (Mimamsa), and cosmology (Vedanta). These are the six darshanas of Indian philosophy. More particularly, sages have argued that the yogic journey into the deepest point of our being, a practice that is popularly called ‘Tantra’, is the quickest way to understanding.

As our ordinary conception of who we are is determined by name and form (Namarupa), this journey requires challenging our most basic beliefs related to our personal and social selves. One needs to travel to the deepest layers of our being wherein spring our desires, some of which are primal and others that are shaped by culture and experience. Since name and form belong to the realm of time and change, this path is that of the Goddess. The path of the Goddess is quick, but it is filled with danger since it involves deconstructing one’s self and then arriving at a new synthesis. This path has been popular with warriors, intellectuals and aesthetes and its practitioners include India’s greatest philosophers.

We explore first the question of the antiquity of the Sri Chakra by showing that it figures in a very early text, the Svetashvatara Upanishad (SU). The deity of the Sri Chakra is known to us from the Brahmaṇḍa Puraṇa as Lalita Tripurasundari, the playful transcendent beauty of the three cities. The meaning of the Chakra and its nine circuits will be explained.

Svetashvatara’s Yantra

The sage Svetashvatara, who belonged to the late Vedic period, asks in his Upanishad whether time (Kala) or nature (Svabhava), or necessity (Niyati) or chance (Yadṛccha), or Puruṣa is the primary cause of this reality. He answers in a riddle that goes:

tamekanemi trivṛtaṃ ṣoḍaSantaṃ Satardharaṃ viṃSatipratyarabhiḥ aṣṭakaiḥ ṣaḍbhirviSvarupaikapaSaṃ trimargabhedaṃ dvinimittaikamoham .1.4

Who (like a wheel) has one felly with three tires, sixteen ends, fifty spokes, twenty counter-spokes, six sets of eight, one universal rope, with three paths and illusion arising from two views. SU 1.4

This looks like the description of a Yantra, but we don’t have enough information on how to proceed to draw it. An interpretation of these numbers as different categories of Sankhya was provided by Shankara (788-820) although he did not specifically address its graphical design.

We argue that this describes the Sri Chakra. This might appear surprising at first because the Svetashvatara Upanishad extols Rudra-Shiva and the Sri Chakra is associated with the Goddess. But since Shiva does reside at the innermost point (Bindu) of the Chakra along with the Goddess, it is not inconsistent with the focus of the Svetashvatara Upanishad. Furthermore, SU 4.9 proclaims: mayaṃ tu prakṛti vidyanmayinaṃ tu maheSvaram, consider Nature to be magical (Maya) and the Great Lord (Mahesvara) to be the one who has cast the spell (Mayin). The Goddess is another name by which Nature is known, therefore the mystery of the Lord in the launching of the Universe can only be known through the Goddess. The identification of the Sri Chakra in SU goes against the scholarly view that the Sri Chakra is a post-major-Upanishadic innovation, and, if accepted, this calls for a revision of the history of the development of Tantra.

The Bindu or dot in the innermost triangle of the Sri Chakra represents the potential of the non-dual Shiva-Shakti. When this potential separates into PrakaSa (the Aham or I-consciousness, Shiva) and Vimarsa (the idam or this-consciousness, Shakti) it is embodied into Nada, Kala and Bindu. Nada is the primal, unexpressed sound (interpreted by human ear as Oṃkara) and Kala is the “Kama Kala,” the desire to create, which the Vedas tell us is the desire “May I be many” (Chandogya Upanishad. 6.2.1.3). Bindu, as the potential universe ready to separate into various categories is Mahatripurasundari. Shiva as Prakasa (luminosity or consciousness) has realised himself as “I am”, through her, the Vimarsa Shakti (nature as the reflector).

It must be stated that within the Yogic tradition, it has always been believed that Tantra is a part of the Vedas itself. In the Devi Sukta (Rigveda 10.125), the Goddess describes herself as supreme. In the Sri Sukta of the Ṛigvedic hymns (appendices), the goddess Sri is associated with prosperity, wealth, and fortune, and she is spoken of as deriving joy from trumpeting elephants. The Sri Sukta, addressed to Jatavedas of Fire, was invoked at the fire ritual. In Kauṭilya’s Arthashastra (14.117.1) there is reference to the goddess being invoked for the protection of a fort. In the Bṛhadaraṇyaka Upanishad 7.4 there is a reference to the goddess Vac.

The Vedic triads, together with the dyadic male and female components, enlarge through expansion (Prapanca) so the universe is a projection (Vimarsa) of the Absolute’s self-illumination (Prakasa).

The supreme deity in the form of Shakti (Parashakti), Sri as the great goddess (Mahadevi) is one of the aspects of Lalita Tripurasundari. Lalita Tripurasundari has three manifestations: Sthula, or descriptive as image; Sukṣma, or subtle as mantra; and para, or transcendent as Yantra or Chakra. Lalita Tripurasundari is also called Rajarajeshwari or just Sridevi. Those who see the three representations as interrelated are called the followers of the Kaula tradition, as has been the case with the Kashmiris.

In the South, the Tirumantiram (Srimantra in Sanskrit) of the seventh century siddha Tirumular knows Srividya. In the Lalitasahasranama, Lalita is described in terms similar to those of Durga. Lalita is worshiped as the Srividya mantra and as the Sri Yantra.

The Srividya mantra is known in three forms: kadi (starting with ka), hadi (starting with ha), and sadi associated with Sri Manmatha, Lopamudra, and Durvasa respectively. The mantra is divided into three parts, which represent three sections (kuṭa or khaṇḍa) of the image of the Goddess: Vagbhavakuṭa, Kamarajakuṭa, and Shaktikuṭa.

The kadividya of Sri Manmatha: ka e i la hrim (vagbhavakuṭa) ha sa ka ha la hrim (kamarajakuṭa) sa ka la hrim (Shaktikuṭa).

The hadividya of Lopamudra: ha sa ka la hrim (vagbhavakuṭa) ha sa ja ha la hrim (kamarajakuṭa) sa ka la hrim (Shaktikuṭa)

The sadividya of Durvasa: sa e i la hrim (vagbhavakuṭa) sa ha ka ha la hrim (kamarajakuṭa) sa ka la hrim (Shaktikuṭa)

The 18th century scholar Bhaskaraya maintained that the Srividya mantra is meant in Rigveda 5.47.4 where it is said: catvara iṃ bibharti kṣemayantaḥ, “that with four iṃs confers benefit”. The kadi mantra (pancadaSakṣari) has four long i vowels. According to some, the 16-syllable mantra (ṣoḍaSakṣari) is obtained by adding the seed-syllable (bijakṣara) Sriṃ to the 15-syllable mantra.

The Sri Vidya mantra is viewed as 37 syllables, representing the 36 tattvas of reality of Saivism and the 37th transcendent Parashiva state. These are divided into 11 for the Vagbhavakuṭa, 15 for the Kamarajakuṭa, and 11 for the Shaktikuṭa.

The Sri Chakra and Lalita Tripurasundari

The three cities in the name of Lalita Tripurasundari are that of the body, the mind, and the spirit, or that of will (Iccha), knowledge (Jnana) and action (Kriya). They may also be seen as the knower, the means of knowledge, and the object of knowledge; the three gunas of Sattva, Rajas and Tamas; Agni (fire), Surya (sun) and Chandra (moon); Sṛṣṭi (creation), Sthiti (preservation) and Laya (dissolution); intellect, feelings, and sensation; subject (mata), instrument (mana), and object (meya) of all things; waking (jagrat), dreaming (svapna) and dreamless sleep (suṣupti) states; as Atma (individual self), Antaratma (inner being) and Paramatma (supreme self) and also as past, present and future.

Her five triangles represent the Pancha bhutas (five elements). She holds five flowery arrows, noose, goad and bow. The noose is attachment, the goad is revulsion, the bow is the mind and the flowery arrows are the five sense objects. Their union is harmony or samarasa.

Shankara (788-820) spoke of the Sri Chakra in the Saundaryalahari (SL) (Subramaniam, 1977). In SL11, the Sri Chakra is described in terms of its four Srikaṇṭha (upward pointing) and five Shivayuvati (downward pointing) triangles, which create its 43 triangles. If we look Sri Chakra’s structure as consisting of three basic triangles, then within each triangle are lower hierarchical levels of two other triangles, of alternating polarity. The 42 outer triangles are arranged in four circles around the middle triangle, with counts of 8, 10, 10, and 14 in the four arrays. The Sri Chakra is also associated with the Chakras of the yogi’s body. According to SL 14:

Fifty-six for earth (Muladhara); for water fifty-two (maṇi-puraka), sixty-two for fire (Svadhiṣṭhana); for air fifty-four (Anahata), seventy -two for ether (Visuddhi); for mind sixty-four (Ajna Chakra) are the rays; even beyond these are your twin feet.

The six Chakras are classified in granthis (knots) of two. The lowest two chakras correspond to 108 rays, the middle two to 116, and highest two to 136 rays. I have argued elsewhere that this provides an explanation for the layout of the great Shiva temple at Prambanan in Indonesia (Kak, 2010)

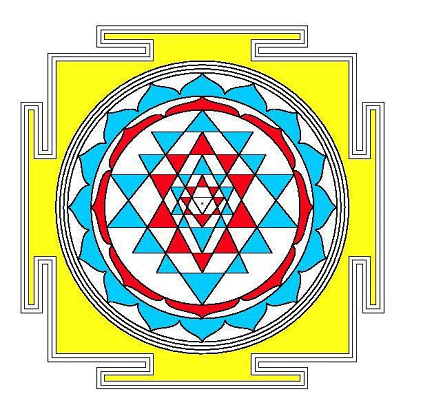

The Sri Chakra embodies the tripartite division of the cosmos into earth, atmosphere, and the sun, which is mirrored in the individual by the body, the breath, and the inner lamp of consciousness; it also represents the three parts of the body: neck to head, neck to navel, and navel to the bottom of the trunk. It is within the wheel of time (kalaChakra), and it is both the human body (microcosm) and the universe (macrocosm) . Its middle 43 triangles are surrounded by a circle of eight petals that, in turn, is surrounded by a 16-petalled circle. At the outermost are three lines, which are called the bhupura. They are also categorised into nine circuits or Avaraṇas, where the bhupura is the outermost avaraṇa. These nine avaraṇas have 108 presiding Devis. In the Sri Chakra puja they are systematically worshipped one by one with their names and mantras. The nine circuits symbolically indicate the successive phases in the process of becoming.

The nine chakras are compared in the Tripura Upanishad to the nine yogas, namely the eight familiar ones of Patanjali and the additional one of sahaja.

Lalita Tripurasundari’s three Shaktis, which are shown in the three corners of the inner triangle, are Bhagamalini, Vajresi, and Kamesvari, who are associated with Brahma, Viṣṇu, and Rudra. The central bindu is where the Goddess is united with Shiva, the Universal Consciousness.

Chakra puja or Yantra puja is the worship of the deity. Devi, the cosmic female force, is the first step of creation. The counterpoint male principle has three emanations: Rudra from the left, Brahma from the middle, and Viṣṇu from the right. At the centre of the Sri Yantra is Kamakala, which has three bindus. One is red, one is white and one is mixed. The red bindu is Kurukulla, the female form; the white bindu is Varahi the male form; and the mixed bindu is the union of Shiva and Shakti

Looking at the Sri Chakra from outside in within the circular part of the Yantra, we thus have one felly with three tires, 16 ends of the petals in the outer circle, and a total of 50 (eight petals and 42 triangles outside of the central one) “spokes”, with 20 triangles in the middle two circuits that may be termed “counter-spokes”, a total of six circuits of petals and triangles have either eight or more than eight members, the universal rope is the Bhupura, the three paths are the paths ruled by Tamas, Rajas, and Sattva embodied by the three goddesses in the innermost triangle.

The Sri Chakra maps the inner sky as one goes from outside to inside; it is also located in the body in terms of the six Chakras. The count of 50 of the Sri Chakra is mapped to 50 petals of the Chakras as one goes from the base (muladhara) to the ajna Chakra. The specific number of lotuses is 4, 6, 10, 12, 16, and 2. The Sahasrara Chakra’s 1,000 petals parallel the infinity associated with the innermost triangle of the Sri Chakra.

Inside the square are three concentric circles, girdles (mekhala) . The space between the square and three girdles is the Trailokyamohana Chakra, or the Chakra that enchants the three worlds; at this stage the adept sees himself as his social self completely immersed in the magic of life.

Next are two concentric rings of 16 and eight lotus petals respectively. The first of these is Sarva Saparipuraka Chakra, which is the Chakra that fulfils all desires; the second is the Sarvasankṣobhaṇa Chakra, indicating dissolution of apartness and duality.

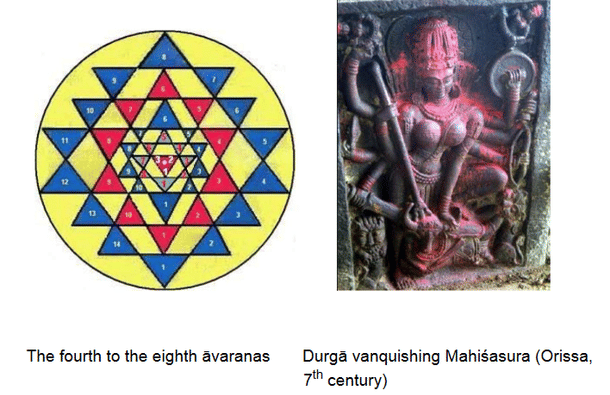

The fourth Chakra, consisting of the fourteen triangles forming the outer rim of the complex interlocking of triangles, is the Sarvasaubhagyadayaka, giver of good fortune, which leads one to spiritual insight and success.

The next two Chakras are each constructed of ten triangles. Called Sarvarthasadhaka, making all means effective, and Sarvarakṣakara, protecting the unifying thread in all experience, they indicate stages when inner realisation begins to strengthen. The seventh Chakra, consisting of eight triangles, is the Sarvarogahara, removing all attachment to duality, at which the sadhaka is near deep transformation.

An inverted triangle is the eighth Chakra of Sarvasiddhaprada , that provides all powers and validation. The last Chakra, the bindu, is Sarvaanandamaya, full of bliss. It is the heart of one’s self in which one witnesses the union of one’s own nature and spirit, Shakti and Shiva.

The Sri Yantra and its worship encompass the deepest secrets of Vedic knowledge. Not only does it represent the inner cosmos, which has the framework of infinity and recursion across scale and time and a mirroring of the outer and the inner, the ritual associated with it is the heart of yajna.

The Chakra is a representation of Devi in many forms: Lalita, Katyayani, Kameshwari, Kamakṣi, Durga, Caṇḍi, Kali, Amba, and so on, that is reality (Sat), mind (Chit) and bliss (Ananda). As Mahavidyas, Devi has the forms Kali, Tara, Tripurasundari, Bhuvaneshwari, Chinnamasta, Bhairavi, Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, Matangi, and Kamala (Lakshmi).

The Sri Yantra ritual infuses the yantra with mantra that represents the union of space and sound. Its closed, concentric circuits (maṇḍalas) correspond to the nine planes of consciousness of the sadhaka. Each plane is a stage on the ascent of one’s being toward the inner self.

The vowels and consonants of Sanskrit are inscribed in the vertices of the Sri Yantra (Abhinavagupta, 2005). In each of the nine circuits (Avaraṇas) specific deities are invoked. The deities are like veils concealing the deeper essence. After the sadhaka has invoked all the devatas in the prescribed manner, he obtains an insight in which all the deities of the plane are fused to become the presiding deity of the circuit.

The Nine Avaranas

The Bhupura is the first (outermost) avaraṇa of the Sri Chakra. These lines have 10, 8, and 10 devis respectively. They include the eight Matrika Shaktis, which are the psychological forces that spring out of ego. The second Avaraṇa has 16 petals in which reside 16 devis that rule over different aspects of physical well being. The third Avaraṇa is the eight petal circle with eight devis who represent various actions as well as non-action. The first three Avaranas represent sṛṣṭi, or extension of creation

The fourth avaraṇa is the outer set of 14 blue triangles, which represent the 14 worlds and the 14 main nadis in the human body; the fifth avaraṇa consists of 10 red triangles; the sixth has the inner 10 red triangles; these three avaraṇas represent sthiti, or preservation. The seventh is the inner eight green triangles; the eighth is the inner triangle. The three corners of this triangle are: Kameshwari, the Rudra Shakti or Parvati; Vajresi is the Vishnu Shakti, Laksmi; and Bhagamalini is the Brahma Shakti, or Sarasvati . The ninth avarana is the bindu, which is the cosmic union of Shiva and Shakti. The deity, Maha Tripurasundari, is the personification of Para Brahman. These three avaraṇas represent samhara, or absorption.

Do the nine sheaths stand up to scientific scrutiny? Modern neuroscience has not yet reached a level where the sheaths covering the innermost sense of self can be examined in the laboratory (Kak, 2004). But it does speak of centers that mediate different aspects of selfhood. The nine sheaths, in the Sri Chakra, are a consequence of the interplay between the realities of various kinds of triads that were mentioned before. To that extent, the nine sheaths are a reasonable way of representing the inner space of our being which is validated by the experience of the sages.

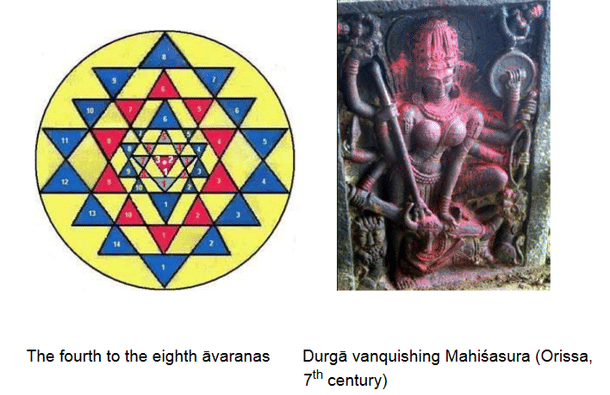

The Devi Mahatmya presents an account of what Mahakali, Mahalakshmi and Mahasaraswati do to bring about the transformation of Prakṛti from Tamas to Rajas, from Rajas to Sattva and from Sattva to Supreme Vijaya, which is mastery in the absolute. The Navaratri is a form of Sri Chakra puja where the nine nights represent the nine avaraṇas. The first three days are a worship of Mahakali, Mahalakshmi and Mahasaraswati; on the subsequent days, their exploits are celebrated. The completion of the sadhana is the marriage of Shiva and Parvati. The process is like overcoming the demonic materiality of one’s own self that is represented elsewhere by Ravana. This victory is celebrated on the tenth day (Vijayadashami) as that of Durga over Mahishasura.

In Kashmir, the goddess Sarika Devi subsumes in herself all the nine avaranas, which is why she is shown with nine sets of arms.

We have seen much overlap between the numbers described in the Svetashvatara Upanishad and those of the Sri Yantra. In our opinion the case for the two yantras being the same is compelling. The conception of the Goddess as the Supreme power out of which all the Gods emerged, encountered in the Durga Saptasati, existed at the time of the Svetashvatara Upanishad for it is also proclaimed in the Devi Sukta of the Rigveda (10.125). Furthermore, we have evidence of yantric structures in India that go back to about 2000 BC (Kak, 2005) as well as representations of the Goddess killing the buffalo demon from the Harappan period, so we are speaking here of a very ancient tradition.

The Sri Chakra is an iconic representation of the deepest intuitions of the Vedas. It represents both the recursive structure of reality and also expresses the fact that Nature and Consciousness are interpenetrating (Kak, 2007). It is relatively easy for the conditioned mind to question names and forms (Namarupa) as compared to turn the gaze of one’s inner mind on one’s consciousness. The Sri Chakra looks at reality through the lens of beauty and felt experience. By helping one penetrate the various coverings of one’s mind, it takes the seeker to Shiva, the fixed point of one’s self.

References

Abhinavagupta, 2005. ParatriSika Vivaraṇa. Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi. S. Kak, 2002. The Gods Within. Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi.

S. Kak, 2004. The Architecture of Knowledge. CRC/Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.

S. Kak, 2005. Early Indian architecture and art. Migration and Diffusion – An International Journal, vol. 6, Number 23, pp. 6-27.

S. Kak, 2007. The Prajna Sutras: Aphorisms of Intuition. DK Publishers, New Delhi. S. Kak, 2010. Space and order in Prambanan. OSU.

V.K. Subramaniam, 1977. Saundaryalahari. Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi.According to the Vedic view, reality, which is unitary at the transcendental level, is projected into experience that is characterized by duality and paradox.

Subhash Kak is Regents professor of electrical and computer engineering at Oklahoma State University and a vedic scholar.