Economy

Explained In-Depth: The Three New Schemes Launched By Modi Government To Make India A Global Hub Of Electronics Manufacturing

Arihant Pawariya

Jun 05, 2020, 07:10 PM | Updated Jun 30, 2020, 03:57 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Since 2014, India has come a long way in electronics manufacturing, making it one of the biggest successes of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambitious ‘Make in India’ project. The country was producing $29 billion worth of electronics in 2014 and imports stood at $38 billion. In 2018-19, production jumped to $70 billion and imports increased to $57 billion.

This huge jump was mainly contributed to by mobile device manufacturing which rose from a value of a paltry $2.9 billion to $24.3 billion.

India is now the second-biggest hub of mobile manufacturing in the world. In 2014, there were only two mobile handset manufacturing units. In 2019, there were more than 200. In 2014, 60 million mobile handsets were produced in India. In 2019, that number jumped to 330 million, more than a five-fold increase.

Other areas like production of computer hardware, strategic electronics, consumer electronics, electronic components, industrial electronics also improved from the 2014-15 levels.

Thanks to this significant addition in production, around 2 million jobs were created, directly or indirectly.

Bolstered by this success, the government now wants to build on it and be a global hub for mobile and components manufacturing with an aim to not only meet the demand of the local market but also be an exporter to the world.

As outlined in the 2019 National Policy on Electronics, the idea is to attract global leaders and their supply chains to ‘make in India for the world’.

Between 2014-15 and 2018-19, some key sectors which have shown growth potential apart from that of mobile handsets are LCD/LED TVs, other LED products, auto electronics, medical electronics, industrial electronics, strategic electronics (defence equipment) and telecom products. These will be the focus areas for ramping up production in the coming years for the government.

Towards that goal, the government had unveiled new schemes in April.

On 2 June, the Minister for Electronics and Information Technology Ravi Shankar Prasad, held a press conference where his department officials released detailed guidelines about the three new initiatives of the government which are aimed at increasing electronics manufacturing rapidly by 2025 and create additional 1.5-2 million new jobs in the short term.

These three new schemes are:

— Production-linked incentive (PLI),

— Scheme for promotion of manufacturing of electronic components and cemiconductors (SPECS)

— Modified electronics manufacturing clusters (EMC 2.0).

The total value of the monetary incentive is Rs 50,000 crore with the goal of increasing value of locally manufactured electronic products to $106 billion (from $70 billion in 2018-19). The target for exports is $77 billion.

1. Production-linked incentive or PLI (total value: Rs 40,951 crore)

Though local production of electronics increased from $29 billion to $70 billion from 2014-15 to 2018-19 with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 25 per cent, India’s share in global electronics manufacturing is still in low single digits (3 per cent to be precise).

The biggest constraint still remains the lack of large capital investments in this sector in the country.

Given that Indian firms are also nearly absent in this field makes things worse.

Domestic demand for electronics hardware is expected to skyrocket to $400 billion by 2025 and if India doesn’t get its act together on local manufacturing of electronics, then it will have to pay dearly in terms of import bill shelling out precious foreign exchange.

The PLI scheme is aimed at removing the constraint of large capital investments.

The government will provide a financial incentive for few selected firms if they invest a certain amount of money over the next five years.

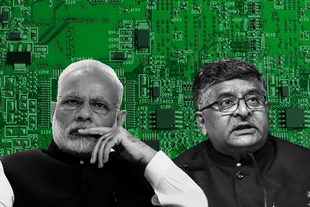

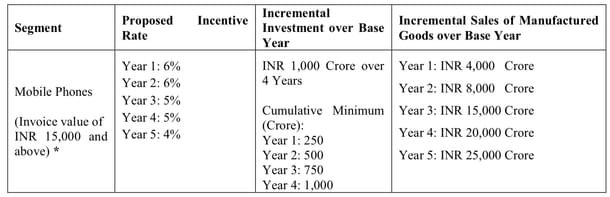

The incentive will be 4-6 per cent of the incremental sales in 2019-20 (base year) for certain goods manufactured in India. The eligibility criteria is given below.

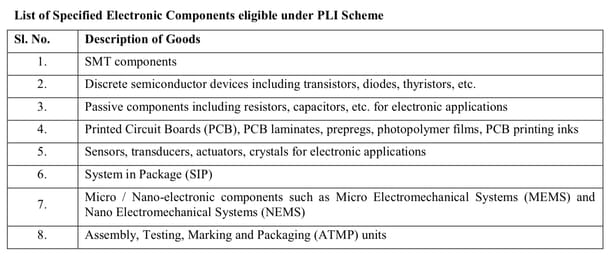

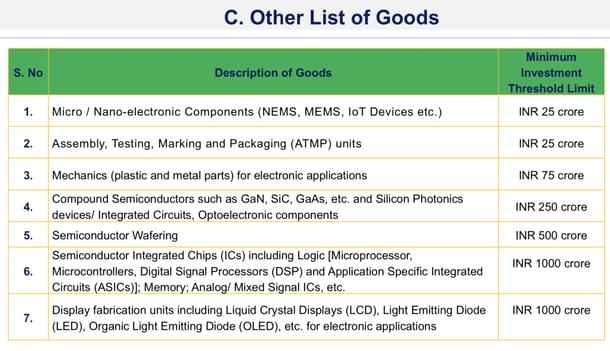

Under the last segment, electronic components specified include:

Of course, in the first segment of foreign mobile companies, only those will be selected which have a consolidated global manufacturing revenue of Rs 10,000 crore or more. The idea is to focus on attracting only major players.

Domestic companies with revenue of Rs 100 crore would qualify. Since there are only a limited number of domestic firms and that too small in size, the criteria for them are kept much lower.

In the third segment, firms with global revenue of Rs 50 crore can also apply. A total of 20 players will be selected (five each in first two segments and 10 firms in the third segment).

Let’s say if eight firms apply in the first segment, then five will be picked based on their global revenues. Ditto for other categories.

Now, monetary incentive will be calculated as the net incremental sales multiplied by rate of incentive in that year.

For example, if a firm invests Rs 250 crore more in 2020-21, than it did during 2019-20, and if its net sales in 2020-21 are Rs 4,000 crore more than in the previous year, then the government will disburse Rs (6 per cent x Rs 4,000 crore = Rs 240 crore) to that company.

If the same company is able to manage incremental sales of say Rs 10,000 crore rather than Rs 4,000 crore in 2020-21, then the government will give it Rs 600 crore and so on.

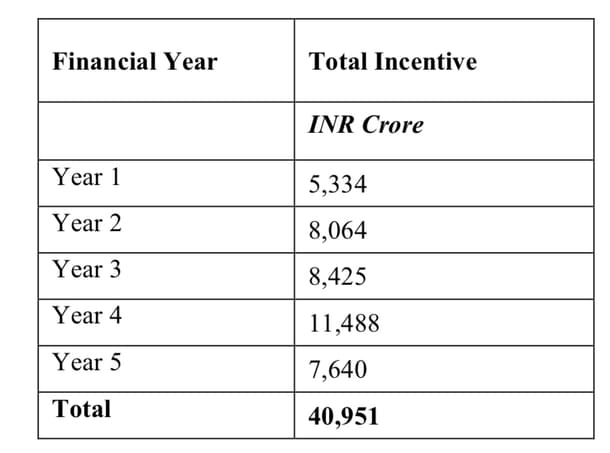

There is a yearly cap on disbursements, of course. In the first year (ie 2020-21), the government will divide Rs 5,334 crore between 10 selected companies (foreign and domestic). If there are less number of companies (say six instead of 10) then the leftover money won’t lapse but will be divided between those six companies based on their sales.

Of course, only those companies will be selected that invest a certain amount of money. Minimum investment needed to be eligible for the scheme is Rs 1,000 crore in four years (until 2024-25) for foreign mobile phone manufacturers, Rs 200 crore for domestic mobile phone companies and Rs 100 crore for components manufacturers (foreign or domestic).

Investment here doesn’t refer to expenditure on buying land/buildings but spending on plant, machinery, equipment used for manufacturing, research and development, technology transfer agreements and spend on other associated utilities (power, effluent plants, IT infrastructure, etc).

2. Scheme for promotion of manufacturing of electronic components and Semiconductors or SPECS (total value: Rs 3,285 crore)

Mobile manufacturing in India may have improved drastically from $2.4 billion to $24.3 billion from 2014-15 to 2018-19 but one major criticism that remains is that most of it is on account of mere assembly of imported electronics components, sub-assemblies and parts catering to local demand. Thus, there is little value addition.

This is due to the absence of local supply chains manufacturing important electronic components, semiconductors, display, etc. Without developing local ecosystems and supply chains for these components, the growth in mobile manufacturing can’t be sustained for long.

There are a number of reasons why India lags behind in developing this ecosystem.

One big impediment is that there is zero duty on imports of electronic components/semiconductors, thanks to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) mandate.

At the same time, the import duty on finished product is much higher.

So, it makes sense for companies to assemble in India and sell the product here, rather rather than import the final product whose cost becomes unviable for most consumers.

Other factors are high cost of capital to set up global scale capacities, inadequate infrastructure, inadequate power/water supply at competitive rates, high logistics cost, etc.

To alleviate the issue of high capital costs, the government has launched SPECS under which it will provide a financial incentive of 25 per cent of capital expenditure that companies spend on setting up manufacturing base in India for certain electronic components.

So, the government will be effectively financing one-fourth of the spend by firms on plant, machinery, equipment, associated utilities, IT infrastructure, and R&D. (Land and building costs are excluded from the ambit of the scheme). Just like PLI, expenditure on raw materials won’t be considered as capex spend.

This will cover not only new units but also expansion of existing establishments.

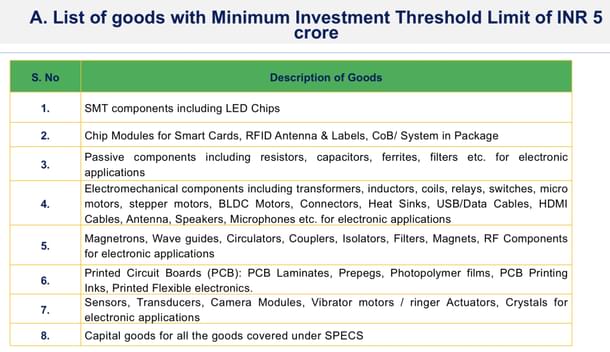

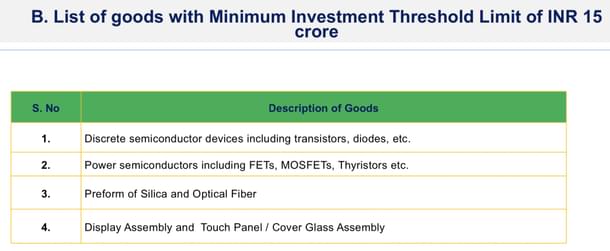

A firm can make a number of applications for different categories of goods for which there is a minimum investment threshold as follows:

3. Modified Electronics Manufacturing Clusters or EMC 2.0 (total value: Rs 3,762 crore)

One of the major impediments to setting up of local supply chains for manufacturing of electronics components is lack of infrastructure and needed facilities. EMC 2.0 is aimed at solving this problem.

It will provide financial incentive to companies for setting up electronics manufacturing clusters (or expansion of already declared clusters) where quality infrastructure is built so that production can be done locally and at scale, thereby helping supply chains.

The minimum area that firms will need to take up to develop as a cluster is 200 acres out of which 70 per cent utlisable area (which excludes roads, green spaces, sewage facilities, etc) must be allocated for setting up of processing activities dedicated to manufacturing of components.

Companies will need to put an investment of at least Rs 300 crore in a EM cluster. One or more companies can decide to take the cluster together and develop common facility centres in existing clusters or industrial parks as well.

The government will finance half of the cost of the project.

However, the government has put a cap of Rs 350 crore as its maximum incentive for one project.

So, if a project worth Rs 600 crore is set up, the government will give Rs 300 crore but if the project cost is Rs 900 crore, the government will give Rs 350 crore only.

There is ceiling of Rs 70 crore per 100 acres as well.

So, if a firm is setting up project worth Rs 400 crore but it is limited to only 200 acres, then the government will give it Rs 140 crore (Rs 70 crore for each acre) rather than Rs 200 crore. To avail the full Rs 350 crore benefit, a company (or companies) will have to take up minimum 500 acres of land as a cluster.

Of course, the remaining 50 per cent cost of the project will have to be financed by state governments, PSUs, and other government agencies. All that the companies have to do is commit to a certain amount of investment, lease, or buy certain acres of land and start production.

The EMCs will receive their first instalment from the government (30 per cent amount) as an advance, second instalment (40 per cent amount) when 80 per cent of the first instalment is spent, and the final and third instalment after the completion of the project.

Arihant Pawariya is Senior Editor, Swarajya.