Economy

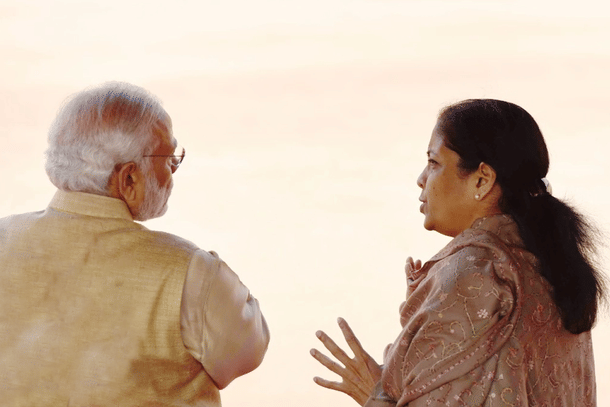

How Modinomics Proved The 'Experts' Wrong: Extreme Poverty Fell Even During Pandemic

R Jagannathan

Apr 07, 2022, 12:49 PM | Updated 12:48 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

You may not know it by listening to the opposition’s harsh comments on Modinomics, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic that saw millions of people either lose their jobs or see a reduction in incomes. For that matter, you won’t find charitable comments about India in the international media either. But a new peer-reviewed paper written by Surjit Bhalla, Karan Bhasin and Arvind Virmani for the International Monetary Fund (read/download from here) shows just the opposite: thanks to in-kind transfers (especially food), India has not only ended extreme poverty (defined as those earning less than $1.9 per day in terms of purchasing power parity, or PPP), but it has done so in the midst of the pandemic. Extreme poverty rates are now well below 1 per cent, which implies that our next target is the lower middle income poverty line of $3.2 PPP daily.

The paper, titled Pandemic, Poverty and Inequality: Evidence from India, comes to three conclusions:

One, both extreme poverty and lower middle income poverty reduced dramatically during the Narendra Modi years.

Two, the Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, reached it lowest level in 40 years in the midst of the pandemic in 2020-21.

Three, this achievement was largely the result of in-kind transfers, especially the doubling of food entitlement from 5 kg to 10 kg during the pandemic, with 5 kg coming free for the poor.

The authors start by pointing out the methodological fallacies inherent in trying to estimate poverty through surveys on household consumption expenditures. These surveys, while useful, tend to over-estimate poverty since they do not account for the value of subsidised goods provided in kind — such a food provided under the Food Security Act (FSA), under which 50 per cent of the urban population and 75 per cent of the rural population is covered. The FSA dates back to the UPA (United Progressive Alliance) era in 2013, but was effectively implemented during the Modi regime, and the entitlements were doubled from 5 kg of subsidised rice or wheat earlier to 10 kg now. During the pandemic, 5 kg of food was even delivered free, along with cash benefits of Rs 500 a month to women, and Rs 6,000 to farmer households.

The reason why poverty got over-estimated earlier is simple: when rice is given at Rs 3 a kg under the FSA, the real consumption expenditure is not Rs 3, but closer to Rs 30, which is the average market price for that commodity. But this is not only about restating what was already achieved earlier; in fact, this level of extreme poverty reduction and maintenance below 1 per cent is the result of a key reform during the Modi years: the Aadhaar-linked delivery of subsidies, which reduced leakages and ensured that the actual beneficiary got her entire entitlement without loss. This applied not only to food subsidies, but also payments under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), or even the minimum support prices paid for foodgrains procured from farmers.

The paper by Bhalla, et al, notes: “The effect of the subsidy adjustments on poverty is striking. Real inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has declined to near its lowest level reached in the last 40 years — it was .284 in 1993-94 and in 2020-21 it reached .292. Possibly the more surprising result from the incorporation of food subsidies into the calculation of poverty is that extreme poverty has stayed below (or equal to) one per cent for the last three years. In the pandemic year 2020-21, extreme poverty was at its lowest level ever — 0.8 per cent of the population. Further, as early as 2016-17, extreme poverty had reached a low 2 per cent level. According to the more appropriate, but 68 per cent higher, low middle income (LMI) poverty line of PPP $3.2 a day, poverty in India registered 14.8 per cent in the pre-pandemic year 2019-20. This achievement is put in perspective by noting that in 2011-12, the official poverty level for the lower PPP $1.9 line was 12.2 per cent.”

Another important conclusion is how low inflation helped reduce poverty even while growth slowed after 2012. The paper says: “Real per capita consumption growth (deflated by CPI) grew at 5.9 per cent per annum (during) 2014-19, higher than the 4.0 per cent growth experienced during the highest GDP growth period 2004-11. It is this consumption growth that is relevant for estimates of head count poverty and inequality. A pointer to why this poverty decline during a lower GDP growth period (2014-19 vs. 2004-11) has happened is provided by the steep decline in inflation — from a CAGR of 8.4 per cent in the high GDP growth period to just 3.6 per cent during 2014-19.”

The paper notes how Modinomics, instead of spending like crazy, focused its pandemic relief on the most vulnerable sections. It notes: “The pandemic relief was provided in three forms. First was to rely on automatic stabilisers and allow them to operate fully while reducing fees and penalties on non-compliance with regulations such as tax filings, etc. Second was to target new expenditures and subsidies carefully to those who were most affected by the pandemic. The third approach was to coordinate with India’s central bank and provide monetary policy support. This was augmented with providing fiscal resources for a credit guarantee programme…Subsequently, the doubling of entitlements in 2020 helped maintain extreme poverty at the low 0.8 per cent level. Without any food subsidies, extreme poverty in the pandemic year would have increased by 1.05 per cent (from 1.43 percent to 2.48 per cent) and LMI (lower middle income poverty with a PPP $3.2 poverty line) by 8 per cent (18.5 per cent to 26.5 per cent).”

The conservative but sensible Modi approach in dealing with the negative fallout of the pandemic has come out trumps.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.