Economy

Railways: Dream, Design & Make in India: I

Sujeet Mishra

Jun 24, 2015, 08:18 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 10:18 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

If we aspire to shift our man and material shipment on to rail, it is imperative to have structures which foster internalisation of technology purchased.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambitious vision of leadership in railway technology, seen with the ‘Make in India’ initiative, presents very interesting possibilities. Make in India is a war cry and in it lies embedded the need of Dream in India and Design in India. Leadership in railway technology isn’t just about railways; this development would be inset in the larger industrial landscaping being envisioned and boldly attempted. Ease of doing business translates into creation of an enabling ecosystem for Dream, Design & Make in India.

Underscoring this vision, the Railway Budget presented this February, announced setting up of four railway research centres in association with universities and one chair in material science in honour of Pt. Madan Mohan Malviya at IIT(BHU). Further, national initiatives in mission mode on Electric Vehicles, Smart Cities and Smart Grids have been rolled out —these are the fields which see immense research efforts across the world. In these three fields lie humanity’s attempt to rewire and hard reboot the urban milieu.

As the country seeks economic salvation in technology-led growth with railroads being central to this vision, it is imperative that we examine the current state of affairs, juxtaposed with the story of the emergence of the Chinese as railway technology exporters and figure out the path accordingly. Also, we need to examine the monies involved and whether we can leverage domestic needs to create the competence being looked at.

On 14 November 1998, Chittaranjan Locomotive Works became second in Asia (after Japan) to have manufactured a modern 6,000 HP electric locomotive with solid state drive (this railway factory was dedicated in the memory of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das on the day we declared ourselves a republic—26 January 1950—and was created with the ambition of becoming self-sufficient in locomotives; being able to make a locomotive was swavlamban personified).

This was one of the finest example of Make in India, as the technology received from Europe was transferred to several private and public entities and a whole new breed of vendors were exposed to the world’s best manufacturing practices and technology. Come 2008, India was once again in the market for electric locomotive technology, and this time apart from the Japanese, the Chinese were serious contenders!

The story of those intervening 10 years is the story of China’s determination to be counted amongst the world’s leading locomotive players, instead of having to live through the ignominy of standing in the market as a yachak. All in a short span of 10 years.

It is instructive to note that the China jumpstarted its locomotive sector about the same time as India and with the same technology providers. But, if the next 10 years were largely downhill for us, for them, they just claimed all that they could survey. Chinese rolling stock has already come into India in a metro system.

Railway Research in India

Rail research in India has been principally carried out by the Railway’s Production Units (PUs; unlike PSUs, these aren’t corporate entities—they are government entities under administrative control of the Ministry of Railways) and RDSO (Research Designs & Standards Organisation, which is treated as a zone of Indian Railways). There has always been an element of overlap between the PUs and RDSO with the thrust of work shifting to the entity with the greater initiative. To give a design focus to the PUs, Centres for Design & Development were created in the PUs in the late 1980s. BHEL at its Bhopal unit also created a design facility and established the country’s only roller test jig (lying grossly underutilized since inception).

What does railway research entail? We need to distinguish between platforms, products and components. Making a Shinkansen (the legendary Bullet Train), a TGV, a metro train, a new coach or for that matter, a locomotive would be platform based research. A new bogie, traction motor or a pantograph would constitute product research. A new alloy of copper to be used for traction motors or new material for the wheel would be component or material level research. For research to be meaningful, it must encompass all the elements. Hence, applied railway research must be framed by platforms followed by products (a not so distant parallel can be the passenger aircraft. An aircraft engine isn’t made by the company whose name the aircraft carries).

Indian Railways always saw research as a subordinate activity. It is ironical that being the only customer of rail solutions—if Indian Railways didn’t lead rail research, it could not have been done elsewhere in the natural course. The system expected small incremental inputs. Still, driven engineers alive to the developments elsewhere in the world undertook work to improve technologies deployed. Short tenures of officers at RDSO—the principal design entity—meant-long term in-house research wasn’t possible.

Notable attempts of world’s leading research were attempted by RDSO in 1980s/90s with BARC. However, failure of railways to keep its design teams intact during the currency of the project and lack of commitment to resolve the inevitable issues which arise in design phase gave these projects and knowledge generated a summary burial.

Over the decades, the system grew accustomed to induct technology from the First World. The in-house research centred about design improvements on existing platforms, products and components with technology infusion from the First World when the options to further improve ran out. The onus wasn’t on the mastery of the technology—with the PUs and RDSO expected to keep the systems running.

Short tenures of officers ensured that the advanced design tools procured arrived by the time they were packing their bags. IR also erred in treating advanced training and inspections overseas as patronage with no expectation from the officials so deputed upon their return. Many a times officials didn’t even work for a day on the platforms they received training on.

Imported products are inspected overseas by sending officials from India. Also with few senior railwaymen posted in Indian missions in Europe, such opportunities have been routinely squandered. This flies in the face of the fact that technological development can’t happen in a disjointed manner. One wonders where we would have been if the ISRO chose to transfer its scientists every few years!

Despite this, there has been enough resident talent which chose to push the envelope, giving sporadic development. Thus, one notices that the systems failed to meaningfully deal with rail research essentially on HR. Nowhere in the world has research been carried out on the strength of tenured researchers—institutional knowledge has to be built layer by layer over a period of time with institutional continuity being central to the process.

Let’s examine Chittaranjan Locomotive Works, the flagship and the oldest locomotive builder of India.

Chittaranjan Locomotive Works

CLW presents a very interesting case where one notices a regular flow of technology which was then further worked upon to make variants suitable for Indian operating needs.

As the world embraced diesel locomotion post WW II, the Ministry of Railways undertook ToT (Transfer of Technology) from ALCO, a failing US locomotive builder in 1962 (this technology was seeded in Diesel Locomotive Works at Varanasi). This locomotive’s bogie (CoCo trimount bogie) was adopted for the indigenously developed class of locomotive, WAM-4 (1970-71) and was thereafter used for WAG-5 class of locomotives (1983-84).

These two locomotives became a mainstay of electric traction and represented fusion of a diesel locomotive’s bogie and standard electrics which were indigenously developed. This development was key to meet IR’s motive power needs especially between 1970-2000. This was a successful platform design effort. However, it needs to be noted that IR undertook ToT from Alstom, France (1968) and Hitachi, Japan (1974, 1983) for traction motors and worked on them to improve their reliability. This was directed infusion of product technology playing an important role in platform development.

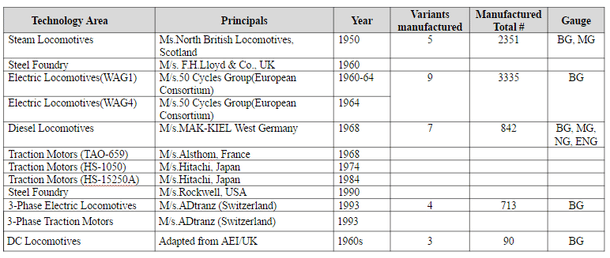

Table 1

List of ToTs undertaken by CLW

After 1960s, IR undertook the first radical shift in motive power technology by adopting three-phase traction technology in step with the emerging global consensus. Accordingly, a ToT agreement was signed on Jul-1993 between Ministry of Railways and ABB Transportation. CLW was mandated to undertake the ToT (not RDSO). A dedicated cell with young engineers was tasked to undertake the complete ToT (know-how) and imbibe know-why as well.The second part of such evolutionary platform designing is seen in WAG-7 class of electric locomotives (1991-92). This development was a crest of a journey where in electric locomotives evolved from 2800 hp (1960s) to 5000 hp on largely common design philosophy—with largely indigenous design resources.

This contract aimed at the import of 22 units of 6000 HP freight locomotives and 11 units of 5400 HP passenger locomotives (partly received in knocked down condition). The passenger locomotives were much lighter and were selected to permit operations at 160-200 kmph. These locomotives were not suitable for 24/26 coach train operations, with frequent start/stops, but were designed for shorter but faster trains.

CLW’s design team undertook customisation of 6000 hp freight locomotive in to a passenger class and thus was born WAP-7 class in 2000 (within 1.5 years of the first indigenous locomotive being built as per the ToT). WAP-7 is now the workhorse for long passenger trains. This transfer of technology was acclaimed globally and was discussed as one of the most successful transfers of technology in the world (Enabling Knowledge Creation: How to Unlock the Mystery of Tacit Knowledge and Release the Power of Innovation, Krogh, Ichiko, Nonaka, Oxford University Press).

However, from this high, how we came about being a yachak in just a few years is an alarming matter—have the lessons been internalised? It has lessons for why India lags seriously in platform and product development despite having spent substantial monies.

A key lesson is discerned when we juxtapose Table 1 with the foregoing—there has been immense potential for platform redesign with Indian Railways. CLW and RDSO handled Steam, Diesels and Electrics and delivered locomotives on all the principal gauges, despite having received technology for one gauge. Accordingly, Indian Railways have supplied diesel locomotives and coaches to Third World countries.

Based on the experience gathered as part of the ToT of new generation three-phase locomotives, CLW led the effort in 2001-02 to participate in a mega locomotive supply and rehabilitation of the South African rail operator (Spoornet) and gave viable bids in competition with companies from whom we aspire to take locomotive technology again (this tender was dropped and Spoornet underwent massive restructuring).

It was interesting that while the new technology was being assimilated and the railway engineers were pushing the frontiers in a globally acclaimed effort, in an act of bureaucratic bloodbath, the core design team was disbanded just four years after first locomotive was turned out. The pleas of not letting go the acquired skills were dealt bureaucratically.

Now Indian Railways are again looking at the Japanese for technology for CLW and trying since 2008 for setting up locomotive factories under PPP. In 2008, when the first round of bidding took place, Chinese, who were behind India in the new locomotive technology in 1990s were very keen to participate!

Though the foregoing dealt with just one aspect of railway research (that is of electric locomotives), the story is not very different elsewhere.

Metros in India and Make in India Compliance

DMRC heralded the Metro age in India. With it came new technologies and massive infusion of modern technology in civil, motive power, signalling and communication. Swanky air-conditioned coaches with automatic doors and Passenger Information System provided salient contrast vis-a-vis suburban trains and circular railways. DMRC insisted that part of the rolling stock should be made in India. Accordingly, BEML set up an assembly line in Bengaluru and Bombardier Transport set up a factory in Gujarat. Alstom has created a factory in Tamil Nadu to meet similar requirements. Bombardier and Alstom serve global markets from these factories.

However, these all remain largely assembly lines with design work remaining firmly overseas. Though metros vociferously argue that their model is the sterling example of make in India—a small little detail that goes unmentioned is that sweatshops are in India but not the real capability to conceive and design—something which is at the very heart of Make in India vision.

The real value creation

The real value creation lies in conceiving platforms, their design, (sub)systems designs and system integration. System integration (components and products assembled to create a platform which can perform in a certain railway network and meet specified load duty) is a key element which would enable India to offer trains in the export market and also deliver better trains for domestic use.

The rail platforms like air frames linger around much longer. Hence, even to contain the cost of ownership, resident system integration skills are needed, which allows part retirement of sub-systems (products). In the absence of local residence of this skill set, the cost of ownership, despite robust contractual binding is likely to be substantially higher even for large Metro operators. For smaller operators, the cost of ownership can be prohibitive.

If we aspire to shift our man and material shipment on to rail in public or private ownership, it is imperative to have structures which foster internalisation of technology purchased and made resident.

Can we in India make this happen?

Dr Sujeet Mishra is a railwayman and currently the OSD of the National Rail and Transportation Institute, which is in transition to become Gati Shakti Vishwavidyala, a central university.