Economy

What The Fourth Industrial Revolution Demands From India

Subhomoy Bhattacharjee

Oct 15, 2018, 04:31 PM | Updated 04:30 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The epochal changes that came about in the working environment of humans since the 1780s determined the flow and ebb of jobs as it is understood today. The First Industrial Revolution as it made its mark in Britain and then in rest of Europe, began to move manufacturing from people’s homes into factories. It also marked the beginning of hierarchical organisation in these factories. Weavers, tanners, iron smiths, who had until then crafted an entire product going solo, were gradually replaced by workers, who did only parts of a job instead of producing a full product, going as a team. For the first time in human history, productivity of the workers began to shoot up within the same generation as each new machine introduced discontinuous changes, instead of rising imperceptibly across generations.

Fledgling urban centres began to emerge often away from the ports and began to dominate the countryside. The scale of change was so radical it became violent at times, as in the famous early-nineteenth-century Luddite riots in Britain. It also changed the place where work was available, so people were forced to move from rural areas to industrial centres. Not surprisingly, this was also the period when nascent labour movements began to emerge.

The Second Industrial Revolution ushered in electrification that expanded the scope of large-scale production. New technologies riding on electrification sprung up in transportation and in communication networks. Those technologies in turn started to cleave the still more or less homogeneous workforce into cohorts. These cohorts began to look at their jobs as uniform within their groups but differentiated with those beyond the cohorts. Thus new professions such as engineering, banking and accountants, or that of teachers sprung up who were extremely aware of themselves as separate groups. It also led to the emergence of a large scale middle-class in the towns which began to impact governance in more and more nations.

Compared to these momentous changes the impact of the Third Industrial Revolution seemed more serendipitous initially. That would change. The key defining role in this revolution was the use of electronics and subsequently that of information technology for production. The advent of computers, the most visible face of the change was greeted with consternation by segments of workers, who assumed that they would be disaster for employment wherever they were deployed. Not just banking, in sectors with deep unions like the railways there was a huge blow back which now seems so ridiculous.

When we examine the changes at a more conceptual level, the Third Industrial Revolution shows up as the phase when human jobs began to migrate to services instead of manufacturing. The first industrial revolution had pulled workers from villages to urban centres to work in factories. That process had deepened in the second phase when large scale assembly line process had vastly speeded up the scale of manufacturing. As workers began to move to services, there was not only an even sharper rise in productivity but it also changed the place from where workers could work. The rigid rules for workers to be present physically in factories and offices began to dissolve. Indeed it created for the first time at a substantial scale the concept of leisure as a viable option for workers to choose from.

Clearly, the lesson from each stage of the industrial revolution is that of disruption. It is quite on the cards that the Fourth Industrial Revolution will also be disruptive, and by all evidence even more so. One of the first change is that work has again begun to seep back into homes from organised centres of production like factories. Indeed for many jobs the difference between humans and machines will disappear. The combined effect of these would be the rise of self-employed workers. It will happen in economies like India at the fastest, since it has less baggage to shed from the earlier industrial revolutions. So people will work more productively but measuring those would become correspondingly difficult as they would not be gathered around in the same building to deliver their results.

This has its own implications down the line. For starters, we shall need to focus on installation of skills and their upgradation at a furious pace. Almost like visiting a shop workers need to find markets where they can buy skills for addressing specific jobs and discard those as they go along. So skills tied into long term jobs will disappear. Skilling then, needs to become a highly evolved industry. If we could determine which skill sets we shall need, we can also set up education centres to provide more opportunities for workers to pick up the skills they need. The role definition of human resource industry, of educational institutions, and of governments would need to radically change for this phase of industrial revolution to take root.

As this happens, it would become necessary to create avenues to shield workers who will be periodically made vulnerable to being displaced by technology. As the scale of disruption expands, people need to believe they have a future. As Adair Turner, former chairman of UK’s financial services authority writes the “striking feature of the modern economy is how few skilled people are needed to drive crucial areas of economic activity”. The trend will deepen.

This means governments along with business and civil society will need to think how to harness the new industrial revolution instead of being a reactive agent. This in turn means it would be politics that would determine the pace of change. Not necessarily technology. This is not surprising as it has been the same in the earlier revolutions too.

In democracies like India this means policies have to deliver regulatory frameworks that change often and with the necessary corrections. This would be necessary in every field, so there may be more law making or more possibly supple rules that would encourage adoption of innovative model. Already there are plenty of those to choose from. In the field of labour, one of the early starters was Denmark’s flexicurity system, now nearly a decade old, where a flexible labour market is paired with a strong social safety net with re-skilling services for all citizens. There would be other variants as artificial intelligence-led technological changes sweep the Earth. Each would demand a customised solution.

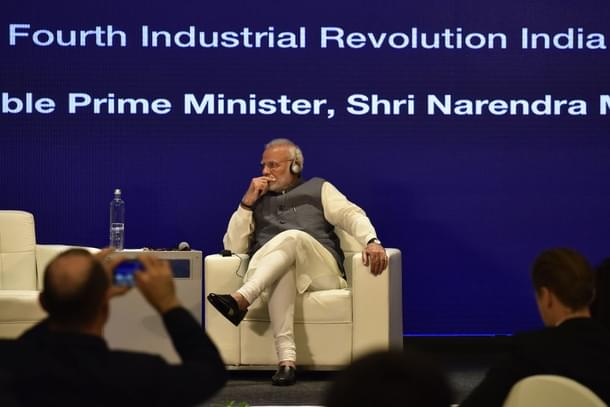

The Indian government’s plans to tap into this revolution is smart thinking. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made all the right noises noting that his “government is willing to change policies to reap dividends of the Fourth Industrial Revolution”. But often after having thought smart, we have in the past let others seize the initiative and therefore the opportunities. India government was the first in Asia to conceptualise special economic zones, it was also the first to conceive a gold exchange. Inertia took care of the rest.

So, unless that is made, it will be facile to argue that new jobs would come up in the economy. They would but in geographies that are smart to create wedges where humans can provide answers that machines cannot. The short point is that technology will advance at a furious pace but the consequent changes will take place over many decades, not as a big bang at one go. This will allow individuals, companies and even societies the time and space to adjust. But to get that window of time opened there is no time for delay now.

Also Read:

Why Was The Industrial Revolution British And Not Dutch?