Economy

World Wants To Break China's Rare Earth Monopoly — Good Luck Trying

Amit Mishra

Jun 21, 2025, 03:15 PM | Updated Jun 25, 2025, 11:20 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

China's much-ballyhooed dominance in rare earth supply chains didn't materialise out of thin air.

In 1992, during a visit to one of the country’s main rare earth production hubs in Inner Mongolia, Deng Xiaoping, the leader who spearheaded China's policy of "reform and opening up," famously commented "while the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths."

What seemed like a bold soundbite then has since crystallised into a “near-monopoly” in the Rare Earth Industry. Against the backdrop, it’s worth asking: How exactly did China build this towering advantage?

Rare — But Everywhere

First, a primer: so-called rare earth elements, or REEs, are actually a basket of 17 elements with overlapping but ultimately unique properties. They include the 15 lanthanides (elements 57 through 71 on the periodic table) plus two chemically kindred outsiders: yttrium and scandium.

The “rare” in “rare earth elements” refers not to the quantity available but rather to their wide dispersion—it’s hard to find an economically meaningful quantity in a single location.

But these unassuming metals punch far above their atomic weight. Without them, there would be no smartphones, no wind turbines, no F-35 fighter jets, no electric vehicles. For example, the F-35 fighter jet contains over 900 pounds of REEs, whereas a Virginia-class submarine uses around 9,200 pounds.

From Byproduct to Monopoly

According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, China’s dominance of the rare-earths industry is the result of a 40-year campaign by the Chinese state.

The story begins in the 1950s at Bayan Obo in Inner Mongolia, where rare earths were originally extracted as a by-product of iron ore mining. For decades, production remained small-scale until the 1970s, when Xu Guangxian, a key figure in China’s nuclear program, found a way to separate these complex minerals. By the mid-1980s, output had surpassed that of the United States, setting the stage for China’s rise as the world’s dominant supplier.

China’s early dominance in the rare earths supply chain began where it was easiest to win: at the mine. Looser environmental standards meant China could extract these minerals cheaply, while stricter regulations forced many mines in the US and elsewhere to shut down.

Today, China so dominates the market that other countries are at a disadvantage. It produces roughly 60 per cent of the world’s supply of rare earths and processes almost 90 per cent, which means it is importing these materials from other countries and refining them.

The Three Stages of Rare Earths — And How China Leads Them All

To understand China’s grip on rare earths, it helps to see the industry as three interconnected stages.

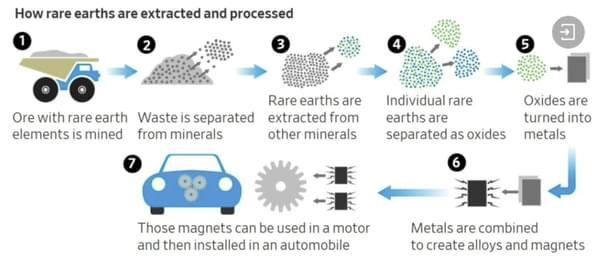

The rare-earth industry can be divided into three stages: upstream, or the mining of elements; midstream, or the processing of elements into separate oxides; and downstream, or the manufacturing of permanent magnets and other components made with rare earths.

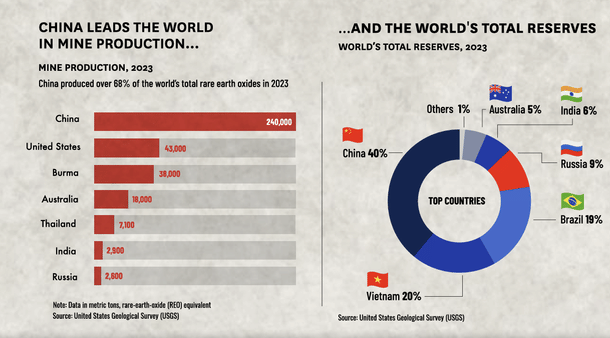

Geologically, China is well-endowed. It holds about 40 per cent of the world’s discovered rare earth reserves— an estimated 44 million tons. India sits in third place with about 6.9 million tons, behind Brazil, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In 2023, global mine production of rare earths reached roughly 350,000 metric tons of rare earth oxide (REO) equivalent. China alone accounted for over 69 per cent of that total. Although this is lower than its peak share of around 90 per cent in 2008, the country remains firmly ahead of anywhere else, with very few signs that that will change in the near future.

“China is blessed with the largest proven reserves in the world,” says Philip Andrews-Speed, Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “The core of the volume is in the North of the country, and that produces mainly light rare earths, while smaller reserves in the South have clays that contain heavy rare earths, which are rare in their occurrence. They have made good use of both of these advantages.”

Yet despite being essential to building a greener future, rare earth metals remain in limited supply thanks largely to the “disastrous” environmental record associated with their mining.

China, in its early push to dominate the market, largely sidestepped these environmental concerns, a trade-off that allowed it to undercut global rivals and cement its early lead.

But that playbook is slowly evolving. In January this year, Chinese researchers announced a more sustainable way to increase rare earth production, while decreasing mining time, energy use and limiting waste.

Based on electric fields, the new method has achieved an “unprecedented” rare earth recovery rate of 95 per cent, while shortening mining time by 70 per cent and achieving electricity savings of 60 per cent. Compared to the high recovery efficiency of this method, conventional mining has a recovery efficiency of only 40 to 60 per cent.

Outside China, a handful of players are trying to claw back market share, but it’s an uphill fight.

The United States, the world’s second-largest producer, which accounted for about 12.3 per cent of global rare earth output in 2023, is leading this effort, with the reopening of the Mountain Pass mine and processing facility in California being a significant step.

But there’s a hitch: producing rare earths profitably in countries with stricter environmental rules and higher labour costs is far more expensive. Industry experts admit that competing with China on price alone is a losing battle unless customers are willing to pay a premium for non-Chinese supply.

Midstream Processing

If mining is the first hurdle, midstream processing is where rare earth dominance is truly decided. And here, China’s grip is nearly absolute.

This stage, known in the industry as separation, involves separating individual REEs from one another in the mined concentrates in the form of rare earth oxides (REOs).

While it sounds simple on paper, creating a pure oxide form of each rare-earth element is extremely complex and time-consuming because each element has to be separated from surrounding materials and from other elements that have similar chemical properties.

When the giant Mountain Pass mine in the Mojave Desert in California, once America’s flagship source, shut down in the early 2000s, it effectively ceded the field to China. With little competition, Chinese processors ramped up capacity, invested heavily in refining techniques, and cemented a near-monopoly on this midstream chokepoint.

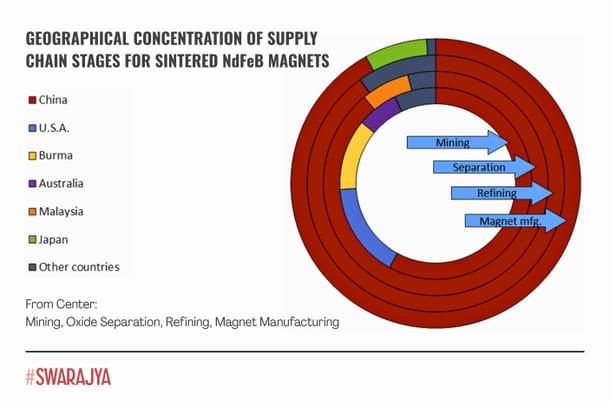

A look at the following image explains the dominance:

Downstream

After the rare earths are extracted and separated, they need to be further refined and processed into powders or different forms. In this stage, they are transformed into specialised materials and alloys through manufacturing, sintering and fabrication processes.

While Japan has carved out a niche in advanced magnet technologies, it's China that calls the shots in this arena too.

Beijing began building this advantage as far back as the 1980s, acquiring key processing know-how from European partners and then systematically scaling up. Today, nearly 90 per cent of the world’s rare earth processing, from oxide separation to magnet fabrication, happens in China.

“The country now easily leads the world in processing technology and in terms of volume. But unlike in critical mineral processing [such as cobalt] where they import most of the volume, for rare earths, China’s refining ability is also backed by its massive reserves, giving them a huge advantage,” says Andrews-Speed.

The extent of this lock-in is stark: currently, there are virtually no commercial facilities outside China that can process heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) at scale.

Alarmed by this, the U.S. Department of Defense aims to build a complete mine-to-magnet REE supply chain on home soil by 2027, a monumental goal given how far behind the U.S. has fallen.

Since 2020, Washington has committed over $439 million to rebuild domestic capacity. This includes funding MP Materials to reopen and expand operations at Mountain Pass in California and to build America’s first fully integrated magnet factory in Fort Worth, Texas.

Yet the scale gap remains daunting. Even when fully up and running, MP Materials expects to produce about 1,000 tons of neodymium-boron-iron (NdFeB) magnets annually by the end of 2025 — less than 1 per cent of the 138,000 tons of NdFeB magnets China produced in 2018.

Developing mining and processing capabilities requires a long-term effort, meaning the world will be on the back foot for the foreseeable future.

The Curious Case of Magnets

For all the talk about rare earths, most people, even seasoned industry watchers, still think of them as simple metals you dig up and run through a factory. It’s a misconception that betrays just how superficial the world’s institutional understanding of rare earths really is.

The same holds true for rare-earth magnets. Producing the world’s most powerful industrial magnets isn’t just about mining minerals; it demands deep R&D, a robust knowledge ecosystem, and precision engineering at every step.

To truly understand why China reigns supreme over the global rare earth supply chain, look no further than its iron grip on neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, which are at the core of everything from motors to transformers.

China produces over 90 per cent of NdFeB magnets, and no other country hosts all segments of the supply chain to make them.

By a quirk of fate, China not only has about nine-tenths of the neodymium discovered on planet earth, but also large swathes of sparsely inhabited land in the Inner Mongolia region, where it refines neodymium without facing as much as a murmur of protest over the environmentally hazardous process.

The result?

Almost every rare earth magnet maker on the planet is, in some way, tethered to China, whether through direct ownership, subsidiaries, or heavy reliance on Chinese raw materials and specialised equipment, says a report from Hudson Institute.

That has not stopped governments and companies outside of China from trying to set up alternative supply chains, but so far with limited success.

Japan, with firms such as TDK and Shin-Etsu, ranks a distant second to China in magnet production and depends heavily on Chinese feedstock for heavy rare earths. South Korea's Star Magnetics, Canada's Neo Performance Materials and Germany's Vacuumschmelze are similarly constrained.

"There's a very limited [number] of alternatives to sourcing those magnets from the Chinese market," said David Merriman, of Project Blue.

A Crack in the Fortress?

Is this monopoly eternal? Not quite, at least if Chinese scientists are to be believed.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently sounded the alarm, predicting that the country’s share of global rare earth reserves could plunge from 62 per cent today to just 28 per cent by 2035 as new deposits come online elsewhere.

Such a candid admission from a state-backed institution is rare. But even as headlines trumpet the prospect of a waning monopoly, the reality on the ground tells a more sobering story.

Yes, rare earth mining has picked up in countries like the United States, Australia, and Myanmar. But here’s the catch: Much of that raw ore still ends up on ships bound for China. Why? Because digging rare earths out of the ground is just the beginning of a complex, resource-hungry process.

Once mined, the ore must be separated into rare earth oxides, refined into pure metals, blended into precise alloys, and finally crafted into powerful magnets that drive everything from smartphones to electric cars. Each step demands huge amounts of land, water, and energy. A few countries can match China’s capacity to supply all three at scale.

It’s also worth noting: “separation” and “extraction” are not the same thing. Each requires specialised know-how and costly infrastructure. Over the decades, China invested heavily in research, patents, and a steady pipeline of university-trained engineers dedicated to improving these steps. The result?

Chinese firms can separate and extract rare earth elements with less energy and higher yields than their global rivals, and then turn them into better, cheaper magnets.

In short, it’s not just what’s in the ground that matters — it’s what you can do with it. And for now, no one does it like China. As the world rushes to diversify and reduce dependency, we must ask: is it too late and too little?