Featured

Modi and the New Wave Cycle

Praveen Patil

Sep 22, 2014, 09:02 PM | Updated Feb 10, 2016, 04:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Psephologist Praveen Patil takes a close look at historical data to reach some very interesting conclusions, and offers a prediction on the shape of India’s polity in the next decade.

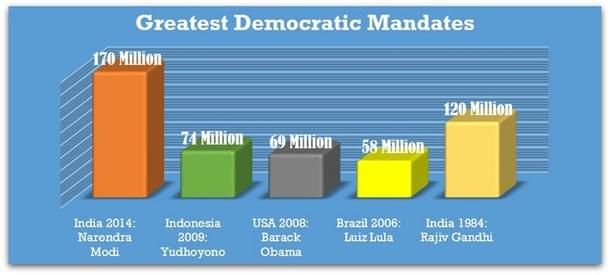

Truth at times must be stripped of its cloak of commentary and be told in bare essentials, for plain truth at times is greater than the narrative surrounding it. Truth be told, Narendra Modi has got the greatest democratic mandate in the history of mankind, for no other leader or political party has got a bigger endorsement from voters in terms of raw numbers. A mindboggling 17 crore or 170 million people voted for Modi’s BJP in the summer of 2014, an unprecedented event in human civilization for its sheer magnitude. To put these numbers in perspective, let us consider this – Barack Obama won the 2012 presidential election by securing 6.5 crore or 65 million votes, while the Modi mandate of 2014 is close to triple that number!

The above numbers aren’t exaggerated by any means to beat around percentages, not in the least. If anything, the above numbers only underplay the Modi mandate by close to 40 million votes because the total vote that NDA secured under Modi’s leadership was 210 million or 21 crore. Furthermore, parties like INLD and MNS – who weren’t part of the NDA – also campaigned in the name of Modi to secure their vote share in the 2014 general elections. For those political pundits who consider Rajiv Gandhi’s 1984 mandate as the gold standard of Indian elections, here is a stunning piece of statistic. In 1984, India’s total population was roughly 74 crore, of whom about 12 crore voted for Rajiv Gandhi, while today India’s population is roughly 125 crore and of whom 21 crore have voted for Modi. In 30 years, even as India’s population increased by roughly 69 per cent, the Modi Mandate of 2014 was actually 75 per cent higher than that of Rajiv Gandhi’s in 1984!

Many political pundits the world over are yet to come to terms with the Modi phenomenon. Quite a few of them still believe this could just be a flash in the pan. There have been and will continue to be umpteen attempts to explain the mandate of 2014 by commentators, columnists, election enthusiasts, out of work television anchors and who have you. There would even be scores of books written in various languages along with hundreds of hours of television programming and reams of argumentative editorials, but would we be any wiser?

Let us consider some oft repeated explanations which have been stretched endlessly by various political pundits to analyse the mandate of 2014. “Modi ran a presidential style campaign and the opposition lacked leadership”, “Congress was on a weak wicket due to wrong perceptions of voters”, “lack of unity in the secular camp”, “communal polarization” etc. Some commentators even live in denial by claiming that “Modi didn’t get a mandate as some 50 per cent odd didn’t vote for him”. Then there are the delusional ones who still believe that by bringing together the entire spectrum of opposition political entities, Modi can yet be defeated.

The editorial-intellectual class of India are habitual offenders, they are just so used to making lazy analysis of the NREGA-won-the-mandate-for-Sonia-in-2009 variety that they cannot fathom anything beyond their ideological constructs. Modi is a problem of mammoth proportions for this class, so everything associated with Modi is visualized as a problem rather than an opportunity to understand the dynamics of a new India. Take for instance, Ramchandra Guha, when confronted with the sheer numbers of support for Modi, once quipped, “Modi (probably) gets support because he speaks fluent Hindi (sic)!”

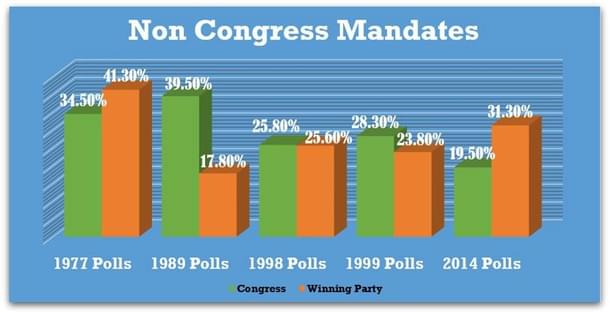

At the data labs of 5Forty3, we back-tested, analysed and correlated the mandate of 2014 over the last few months in order to understand the historic context. The results told us a story that was unique in every aspect from all the elections that India has undergone in the last 65+ years. From such broader themes of this being the first time a non-Congress party getting a majority on its own (even the JP experiment of 1977 was a coalition for all practical purposes) to deeper details of stitching together an unprecedented almost Hindu-only social coalition, 2014 has not only been a history-defying election – whence a non-Congress winner has a comfortable double digit percentage margin over Congress – but also may alter the course of history.

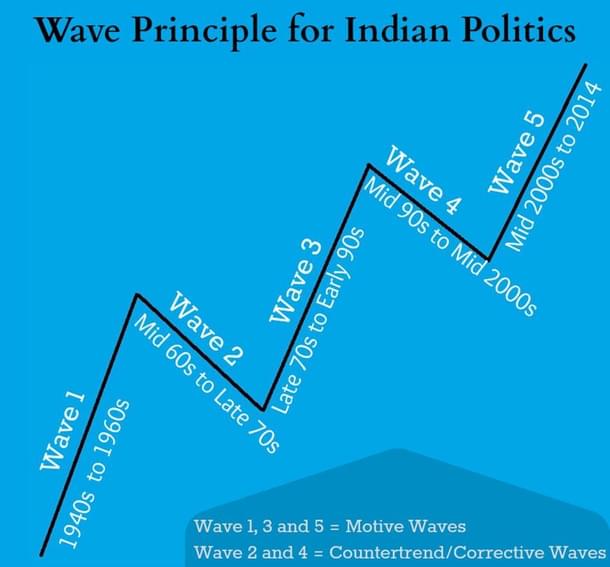

In order to better understand Mandate 2014 in the context of Indian electoral history, we utilized the Elliot Wave Theory which best narrates the cycle of human social nature. The wave principle is based on man’s social nature, and since he has such a nature, its expression generates forms. The repetitive structure of these forms create predictable patterns that best explains mass psychology at different points of time. The fundamental notion of Elliot Wave Theory is based on the Fibonacci summation principle that markets (economy) progress in the form of five waves of a specific structure – three of these waves, labelled as 1, 3 and 5 effect the directional movement and are separated by two countertrend interruptions labelled as waves 2 and 4.

Adopting the wave principle in the context of Indian electoral history, we derive the following waves;

- Motive wave: From the early 1940s (yes, Indian elections preceded independence) to mid-60s, when India was under a one-party rule for all practical purposes and Congress won most if not all the electoral battles.

- Corrective wave: From the mid-60s to the late 70s when the Congress hegemony was challenged nationally by both the Right and the Left; the Right characterized by the likes of Swatantra Party and BJS, whereas the Left was represented mainly by Communists; finally culminating in the JP experiment of 1978.

- Motive wave: From the late 70s to the early 90s when Congress was once again the dominant party at the national level but was fast losing ground in the states – TDP in Andhra, JD in Karnataka and Odisha, CPI(M) in Bengal, Yadavs in the heartland etc.

- Corrective wave: From the early 90s to the mid-2000s, characterized by a coalition era of fractured mandates everywhere, both at the Centre as well as states.

- Motive wave: From mid-2000s to 2014 when people started to vote for stability and governance and clear mandates became the order of the day (a whopping 96 per cent of all elections since 2004 have produced clear mandates)

2014 is an inflection point when history changed its course. On the one hand, the Congress, which was the primary force behind the motive waves of Indian elections was totally decimated, while on the other hand, the dichotomy of coalition politics vs stability was replaced by a new strand of politics of governance. Ideologically too, there were deep-rooted structural changes as development politics replaced secularism politics as the bulwark of Indian democracy. Till now, secularism was used as a cloak to mobilize Muslim votes, now development mantra would be used to mobilize Hindu votes undercover. For all practical purposes, 2014 heralded the birth of a new wave cycle as the five part political wave of the post-colonial India completed its course.

What are the implications of Mandate 2014 for India in the coming decades? For starters, BJP has now replaced the Congress as the dominant political thought of India as this wave cycle will have BJP as the primary motive wave. But that is not all, there is more. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Modi-Shah team in particular have their task cut out, they can potentially mould the 1st primary wave in the shape they desire. BJP can, just like the Congress in the 40s and 50s, create a virtual one-party system of governance in India. In fact, India is ripe for such a political paradigm at this precise moment in history.

As development politics and governance mantra begin to occupy the centrestage of Indian politics, there is a perceptible change in voter intelligence too. For long, I have been arguing that voters in India tend to experiment with a bottom-up approach – for instance, coalition politics was first experimented at the state levels in late 80s and then scaled up to the national level in the mid-90s. Similarly, clearer mandates became a rule in the early 2000s, first in state elections and that experiment was then replicated at the centre in 2009 when Congress and UPA ‘inexplicably’ got a full mandate. The 2014 mandate is likely to change this too. Voter intelligence now suggests that they are willing to experiment with a top-down approach in the new wave cycle of Indian electoral arena.

Over the coming months and years, as the central government led by Modi will try and implement some of the governance ideas that they have developed over the years in BJP-ruled states – 24/7 power, sustainable agricultural growth, push towards infrastructure development and manufacturing – there will be many areas of friction, especially with opposition-ruled states.

We are already witnessing some of this, like say the unresolved issues of power distribution reforms and pricing policy in Congress-ruled Maharashtra and Haryana, leading to increased power cuts and load shedding or the open booing of Jharkhand CM Hemant Soren (incidentally, all these three states will soon go to polls). Thus voter intelligence will logically start veering towards electing Centre-friendly governments in their states in order to take full benefit of this new age development paradigm.

Over the next few months, we will witness four state polls in Maharashtra, Haryana, Jharkhand and Jammu & Kashmir. All of these states have a Congress government in one form or the other and in all of these states, BJP, with or without allies, is a straight contender for power (including J&K where BJP under Shah is trying an unprecedented electoral summersault). If Congress loses power in all these states, as many of the poll surveys suggest, then the party would virtually implode. After losing Maharashtra and Haryana, the only large states that would be contributing funds to the Congress party could be Karnataka and Kerala, which would leave the Gandhis extremely vulnerable to splits.

BJP can also potentially win the big states of the Hindi heartland – Bihar and UP – if it can create strong state-level leadership and more importantly get rid of some of the complacency it has acquired after the Lok Sabha elections (In Bihar for instance, in the recent by-polls, BJP lost at least two seats due to complacency when workers didn’t even manage to mobilize traditional BJP voters on polling day leading to very low voter turnouts). The big test for Shah’s creativity will of course come in Bengal and Tamil Nadu, two states pregnant with immense possibilities for development politics beyond ultra-leftism and Dravidian hyperbole.

It is indeed a distinct possibility that when Modi goes back to the electorate in 2019, vast tracts of India could be saffron country with most states having BJP chief ministers in a virtually single party rule. The only question is whether the Modi-Shah team have the ability and the vision to convert this historic opportunity into a new wave cycle.

Analyst of Indian electoral politics and associated economics with a right-of-centre perspective.