Ideas

Do Hindu Deities Have Rights? Here Is The Case For Giving Them Their Due

R Jagannathan

Jan 20, 2022, 01:40 PM | Updated 01:39 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Do Hindu Deities have constitutional rights? In the context of the growing movement for freeing temples from government control — an outrageous imposition on followers of Hinduism’s various sampradayas — the issue of Deity Rights cannot be brushed under the carpet.

But first, let us get some common objections out of the way. If you are a social justice warrior or someone with rationalist inclinations, you are entitled to ask: how can a murti, whether made of clay, stone or metal, and admittedly made by human beings, be given the same rights as living, breathing human beings?

The answer is simple. Let us first understand that a murti is not the same as what our westernised minds call an “idol”. Murti puja is not idol worship. After it is consecrated, a murti is invested with “life” by priests on behalf of devotees through the prana prathishta ceremony. This point aside, let us ask two other questions.

One, do only human beings have “rights” outside the world of spirituality? The answer is a clear no, for in the judicial world, a non-natural person —whether a corporation or any other legal entity — is also considered a “juristic person” who can own property, be a party to a dispute, pay taxes, etc. In the US, the Supreme Court, in Citizen’s United Versus Federal Election Commission, held that free speech rights exist even for non-natural persons like corporate bodies or their funded agents. So, yes, rights exist for Deities even if you do not consider them to be “persons” in the commonly understood sense of the term. The only question is what kind of rights do they have?

Two, has Deity been accorded person status in the past? Again, the answer is yes. Even when India was ruled by the British, the law accorded the Hindu Deity the status of a minor with rights, with priests and other temple managers only acting as trustees of the minor. This point was established as far back as in 1869, the year of Gandhi’s birth, in a case involving Maharani Shibessourie Versus Mothooranath Acharjo, where the British Privy Council held that the shebait, the manager of the Deity, was only a trustee acting on behalf of the Deity. The trustee had no ownership rights of his own. This principle was reiterated in the Dakor Temple case of 1887, where the Bombay High Court held that the “Hindu idol is a juridical subject and the pious idea that it embodies is given the status of a legal person.” In later cases, the Deity was said to have rights to receive gifts and hold property, among other things.

The issue has come back into public consciousness for two reasons.

One is the Sabarimala case, where a five-judge constitutional bench ruled 4:1 that women in the reproductive age cannot be barred from entering the sanctum sanctorum just because Lord Ayyappa is worshiped as a naisthika brahmachari (eternal celibate). J Sai Deepak, one of the lawyers arguing the case, said that Lord Ayyappa had his own rights as a Deity, which Justice D Y Chandrachud dismissed out of hand: “Merely because a Deity has been granted limited rights as juristic person under statutory law does not mean that the Deity necessarily has constitutional rights.”

This is debatable, for the Constitution is a human document which can be changed, and has been changed repeatedly in 71 years of constitutional history. Nothing stops a government or a court from treating this as another basic structure issue in a country where Deities are worshipped in such large numbers.

Interestingly, the Supreme Court gave more than just juristic status to the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book. In a case involving the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee Versus Som Nath Dass and Others (2000), the apex court said that the “Guru Granth Sahib… cannot be equated with other sacred books… Guru Granth Sahib is revered like a Guru… (and) is the very heart and spirit of gurudwara. The reverence of Guru Granth, on the one hand, and other sacred books, on the other hand, is based on different conceptual faith, belief and application.”

It was the 10th guru, Guru Gobind Singh, the last of the Sikh gurus, who declared that after him the Guru Granth Sahib would be the ultimate and eternal guru for Sikhs. The court, of course, emphasised that the Guru Granth Sahib “cannot be a juristic person unless it takes juristic role through its installation in a gurudwara or at such other recognised public place.”

This logic should equally apply to any Hindu Deity installed inside a temple after due consecration and prana prathistha, which is the act of infusing the murti with prana, making the murti a living entity. If the courts can recognise a holy book as a living guru, and Deities anyway are considered minors with rights, what is the basis for denying the Deity its own individuality and constitutional rights?

The logic here is this: what is worshipped and how depends on devotees, and if the Deity worshipped is seen as the equivalent of a living entity, that is the way it should be.

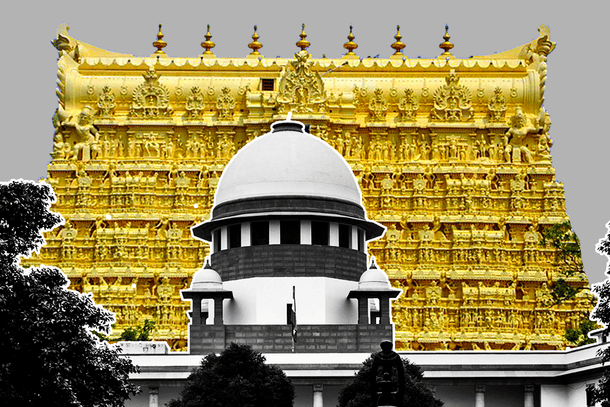

The Supreme Court lost an opportunity to pronounce in favour of Deity rights in the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple case, where the erstwhile rulers of the state of Travancore had a special relationship with this temple of Vishnu in Thiruvananthapuram, the modern-day capital of Kerala.

In 1749, the then ruler of Travancore, Marthanda Varma, took the momentous decision of declaring Lord Padmanabha as the actual ruler of the state, and relegated himself to being his 'dasa', and taking decisions in his name. From then on, all rulers called themselves Padmanabha dasas, and this continued even after the state acceded to the Indian Union after 1947. This linkage between the descendants of Marthanda Varma and the temple remained alive till the courts again entered the picture after allegations of mismanagement were hurled.

In a judgement delivered on 13 July 2020, where the descendants of Marthanda Varma were the main appellants, justices U U Lalit and Indu Malhotra refused to go into the special relationship between the rulers and descendants of Marthanda Varma and their special relationship with the Deity. Instead, the bench merely ruled that Varma’s descendants would be the nominal shebaits/trustees of the temple, aided by two committees — one advisory and another administrative. (Read the full judgement here).

While the Sree Padmanabhaswamy judgement does not restore Deity Rights, it does open up avenues for erstwhile rulers of princely states, who were often the shebaits of various temples, to consider whether they too can return to their traditional roles as managers and benefactors of major temples. The Mysore Royals, for example, have been shebaits to the Mysore Chamundeswari Temple and some others, often built with private funds.

One reason why the Sree Padmanabhaswamy case went partially in favour of the descendants of Marthanda Varma was that the accession of the princely state to the Indian Union was itself done with Lord Padmanabha as ruler. The king acted in his capacity as the Lord’s dasa and representative. In short, the Instrument of Accession of Travancore and Cochin was signed by Shri Chitra Thirunal Balarama Varma as a representative of the Deity in whose name the state was ruled for 200 years before accession.

Commonsense informs us that Deities are critical to Hindu forms of puja or worship. During Islamic rule, when temples were being demolished by bigoted rulers in pursuit of their own iconoclastic inclinations, devotees and priests made it a point to smuggle out the Deity to a safe place when the temple itself could not be saved from destruction. Thus, even more than the temple, the Deity was the life being protected. This fact has been noted in historian Meenakshi Jain’s book, Flight of Deities and Rebirth of Temples.

Today, with the Sabarimala judgement providing a wakeup call to all devotees, the fight for Deity Rights is being led by, among others, Sri Chilkur Rangarajan, the hereditary priest of the Chilkur Balaji Temple in Telangana. But his plea before a nine-judge constitutional bench looking to review the Sabarimala judgement was rejected last year, which has subsequently led to a shift in focus from the courts to the executive.

Letters have been written by not only Chilkur Rangarajan, but also the descendants of Krishna Deva Raya (who took the Vijayanagar Empire to its crest of glory in the early sixteenth century), the Raja of Jatprole and BJP member of Parliament from Bengaluru South, Tejasvi Surya, supporting Deity rights. They have sought the intervention of the President and the Prime Minister to confirm the rights of Lord Padmanabha Swamy, and, in the process, extend the idea to all Deities.

The fight for the return of temples to devotee-led institutions, as opposed to the state running them, will be incomplete without the restoration of Deity Rights. After all, the Deity belongs to devotees, and devotee rights are inseparable from that of the Deity.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.