Ideas

The Temptation And Danger Of 'Reclaiming' Rangpur And Chittagong

Nabaarun Barooah

Jun 13, 2025, 04:36 PM | Updated 04:36 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

When Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma recently turned the cartographic gaze on Bangladesh, he made a point few Indian politicians have dared articulate: that our eastern neighbour, often invoked in the context of India’s own vulnerabilities, has its own “chicken necks.”

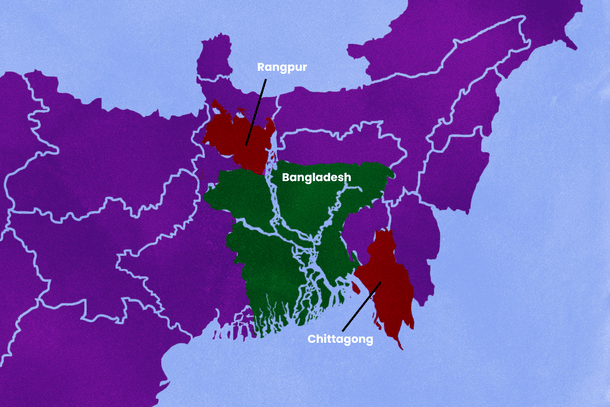

One corridor, just 80 kilometres wide, separates South West Garo Hills in Meghalaya from North Bangladesh and could sever the Rangpur Division entirely. Another, only 28 kilometres wide, links South Tripura to the Bay of Bengal—Bangladesh’s sole connection between its economic and political capitals.

In response, Tipra Motha’s Pradyot Kishore Manikya Debbarma upped the ante. “The Northeast needs its own beach,” he declared, striking a chord with a region long bottled in by the narrow Siliguri Corridor and dependent on circuitous routes for trade and connectivity. For many in the Northeast, this idea is more than strategic; it carries the allure of historical redress.

But behind this realpolitik rhetoric lies a deeper civilisational question: Should India reclaim its ancient frontier lands—Rangpur and Chittagong?

The idea evokes a sense of poetic justice. It stirs memory, mythology, and the trauma of loss. Yet it also conceals a catastrophic risk: importing millions steeped in radicalism, whose forebears once destroyed the very civilisations we now dream of recovering. What was erased by the sword cannot be restored by maps alone—certainly not without consequence.

To better appreciate the risks the risks in 'reclaiming Rangpur and Chittagong', one needs to revisit the Hindu history of Rangpur and Chittagong, the arc of Islamic conquest and demographic upheaval, and the allure and danger of civilisational irredentism in a volatile neighbourhood.

Memory, yes—but not madness.

From Civilisation to Cult: Early History

Long before modern borders cleaved the land, Rangpur and Chittagong stood as vital organs of the Indic civilisational body. Their cultural, spiritual, and political ties to Kamarupa, Bengal, and Tripura run deep—woven through mythology, inscriptions, temple architecture, and martial memory.

One tradition holds that Rangpur’s name derives from the Rangmahal (Palace of Entertainment) built by Bhagadatta, son of the demon-slayer Narakasura and ruler of Pragjyotisha. Myth gives way to medieval memory at Bhitargarh in present-day Panchagarh district, just across Assam’s western boundary.

It was here that Raja Prithu—one of Assam’s greatest forgotten kings—fortified his domain. Known for repelling the early Muslim invader Bakhtiyar Khilji, Prithu eventually took his own life here during the invasion of Nasiruddin Mahmud, refusing to surrender to forces that would soon plunge the region into darkness.

After Prithu’s fall, Rangpur came under the Kamata Empire. Some sources suggest that the name Rangpur actually comes from the word 'Chaturangopur', one of the capitals of Kamteswar Nildhwaj Sen. The word rang means charm, happiness and pur means a city. So the word 'Rangpur' meant the ‘city of happiness’ under the Kamata king.

Later the Koch Kingdom, led by Nara Narayan—a great patron of Hindu art, philosophy, and temple-building, ruled over this land. Koch Behar, under his successors, encompassed Rangpur, and remnants of forts and temples speak to a time when Dharma ruled the frontier.

Chittagong’s history stretches further back, rooted in the ancient kingdoms of Samatata and Harikela—flourishing Buddhist and Hindu domains that extended from Bengal into Southeast Asia. The Chandra and Varman dynasties made their mark here, succeeded by the Palas and Senas, before the Deva dynasty held sway as one of the last great Hindu powers in East Bengal.

The Chinese traveller Xuanzang, who visited the court of Bhaskaravarman of Kamarupa in the 7th century, referred to the Chittagong area as “a sleeping beauty rising from mist and water.” That poetic description belied the military and religious importance of the region. The Shakta traditions of Kamarupa—centered on the worship of the Goddess in her fiercest forms—travelled down to Chittagong. The Chatteshwari Kali Temple stands today as a reminder of that spiritual continuum, one of the revered Shakti Peethas said to mark the sites where parts of Devi Sati’s body fell to Earth.

These regions were not peripheries—they were pivots. They connected Assam to Bengal, Bengal to Southeast Asia, and Indic dharma to the edge of the eastern sea. Their loss was not merely territorial; it was civilisational.

The rise of Islamic power in Bengal and East India marked a turning point for Rangpur and Chittagong—transforming vibrant Hindu polities into contested borderlands, and eventually into Muslim-majority territories.

Chittagong’s Islamisation began when Sultan Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah of Sonargaon conquered it in 1340, incorporating it into the Bengal Sultanate. The region then saw a back-and-forth struggle for control. Tripura’s Dhaniya Manikya briefly reconquered the area in 1513, only to lose it again a year later.

From the late 16th century until 1666, Chittagong was ruled by the Arakanese kingdom—a period marked by trade, piracy, and political instability. Their involvement in Mughal succession conflicts, especially the assassination of Prince Shah Shuja, provoked a decisive Mughal retaliation under Shaista Khan, which ended Arakanese rule and reasserted Mughal dominance.

According to the Ain-i-Akbari, the Mughal General Raja Man Singh first captured Rangpur in 1575, but full Mughal control wasn’t achieved until 1686. By 1611 though, the Mughal Empire had consolidated its hold, embedding itself into the local geography. Names like Mughalbasa (“locality of the Mughals”) and Mughalhat (“market established by Mughals”) still echo this legacy.

The Mughal period in both Rangpur and Chittagong brought demographic shifts, with new settlements and administrative practices promoting Muslim migration and Islamic culture into the region. The slow but steady erosion of Hindu influence began.

These centuries of contest ushered in waves of Muslim settlers, traders, and officials, accelerating the demographic transformation that would render Chittagong a predominantly Muslim region by the colonial period.

From Independence to 2025: The Numbers Story

The gradual Islamisation of Rangpur and Chittagong was accompanied by profound demographic shifts, fueled by migration, conversion, and the displacement of indigenous Hindu and tribal populations.

Historical records show that Hindu populations in Rangpur steadily declined from the late medieval period onward. Census data from British India reflect this shift: in the early 20th century, Hindus comprised roughly 30–35 per cent of Rangpur’s population. By the time of Partition in 1947, this had dropped to about 20 per cent, and today, according to Bangladesh’s 2022 census, Hindus constitute barely 13 per cent of the Rangpur Division.

Meanwhile, the Muslim population in Rangpur has risen from around 65 per cent in the early 1900s to nearly 87 per cent today, consolidating a demographic majority that reflects centuries of settlement and conversion.

Chittagong’s demographic trajectory is even more pronounced. Historically part of the ancient Bengali heartland with a substantial Hindu population, the region saw repeated influxes of Muslim settlers from the Bengal Sultanate and Mughal eras. British colonial census data from the early 1900s indicate that Hindus formed the majority of Chittagong’s population. By 1947, this had fallen to roughly 40 per cent, and in the 2022 census, Hindus account for less than 6 per cent.

The Chittagong Hill Tracts were overwhelmingly non-Muslim, with indigenous Chakma and Tripuri communities making up roughly 98 per cent of the area. However, the upheavals of 1971 brought horrific massacres to Sitakunda, Patiya, Rangunia, and the Hill Tracts themselves, devastating tribal populations.

The demographic shift in the Hill Tracts is especially significant: from 98 per cent non-Muslim in 1947, the population has become nearly half Muslim (44 per cent) today, largely due to state-sponsored Bengali Muslim resettlement programs.

The Muslim majority of the Chittagong Division, now over 90 per cent, encompasses both indigenous Bengali Muslims and those with roots in Indian subcontinent’s broader Islamic world.

These numbers reveal more than demographic change—they reflect cultural and political transformation. Regions that once resonated with Hindu festivals, temples, and Indic governance are today overwhelmingly Muslim-majority, with many Hindu communities marginalized or displaced.

This is the reality behind the rhetoric of reclaiming “ancient lands.” While the memory of a Hindu past is undeniable, the current socio-political landscape is far from that history. To advocate for political reincorporation without reckoning with these demographic truths risks importing large populations who may see such moves not as reunion but as conquest.

What is more concerning is that the demographic shifts that transformed Rangpur and Chittagong centuries ago have long shadows that stretch into today’s India. The systematic demographic invasion of Northeastern states like Assam and Tripura is a broad theme that warrants a standalone article in itself.

The bordering Bangladeshi districts remain hotbeds of radicalisation, fuelling extremist ideologies and violent unrest in both Northeast India and West Bengal. Madrasa networks in these regions have often been implicated in nurturing fundamentalist mindsets that spill across the porous borders. Terror modules traced back to Bangladesh have orchestrated attacks in Assam and Tripura, disrupting fragile communal harmony. Incidents of communal riots, illegal arms trafficking, and extremist recruitment repeatedly find their roots in these adjacent districts.

Certain political parties in border states exploit illegal immigrant populations as vote banks, deepening communal divides and encouraging demographic engineering. Indigenous Hindus and tribal communities live under constant threat, caught in cycles of violence and marginalisation.

This is not mere speculation but the bitter reality of historical demographic aggression taking modern form. The legacy of forced conversions, land dispossession, and cultural erasure from centuries ago has metastasised into contemporary security challenges. The communal fault lines created by history continue to widen, threatening the social fabric of the Northeast and Bengal.

Understanding these radical echoes is essential to appreciating why calls to “reclaim” lost territories are far from benign. They are not simply about geography or history—they are about grappling with present-day threats that originate across those very borders.

Why We Must Not Invite the Enemy In

The impulse to reclaim Rangpur and Chittagong is deeply understandable. These lands are etched into our collective memory as Hindu bastions, lost to conquest and conversion. The idea carries a powerful allure of poetic justice and civilisational restoration.

Yet this impulse, however natural, conceals grave dangers. Reclaiming these territories today would mean inheriting millions of residents who have lived for centuries under a very different cultural, religious, and political order—many of whom harbour radical ideologies hostile to the Indian state and Hindu civilisation.

Rangpur and Chittagong have undergone irreversible civilisational transformation. The Hindu and tribal populations were not simply outnumbered; they were uprooted, displaced, and in many cases, violently extinguished. The Muslim majorities that remain have entrenched social, political, and religious structures incompatible with peaceful integration.

Integrating these populations would not only destabilise the demographic balance but also overwhelm India’s security apparatus. The risk of insurgency, communal strife, and political radicalisation would multiply exponentially. Far from a restoration, such an annexation would invite chaos—threatening the very sovereignty and cultural integrity the idea of reclamation seeks to affirm.

In essence, the mirage of reclamation risks turning a historic injustice into a present-day catastrophe.

Rangpur and Chittagong are poignant chapters in India’s civilisational story—a testament to loss, resilience, and historical shifts. Yet not all that is lost can or should be reclaimed by force or impulse.

Our memories must guide us toward strength, wisdom, and measured strategy—not reckless adventurism. The real battle for India’s future lies within its own borders, in securing demographic stability, cultural integrity, and sovereign control over the Northeast and Bengal.

Reclaiming ancient lands is a seductive dream, but it risks inviting chaos and weakening the very nation it seeks to restore. Instead, India must channel its energies into fortifying what remains, building bridges through diplomacy and development, and preserving its civilisational legacy without succumbing to illusions.

Memory without madness—that is the path to enduring security and national pride.