Magazine

Songs After Sunset: Night Ragas In Hindustani Music

Veejay Sai

Nov 01, 2018, 06:16 PM | Updated 06:16 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Does music have a day and night? While we know it is not bound by time or space, Indian classical music has come down through centuries of tradition that celebrates all hours of the day. There is ample music and dance connected to every auspicious event and festival in India. This Deepavali, let us look at another brighter side of the night through the narrative of Ragas and Raginis, poetry and song. Music of the night is as bright as the lamplight!

Indian classical music has always celebrated the night. Following an ancient clock that sets the day into many sections called ‘Prahars’, each and every hour of the day has some music accompanying it. There is also music associated with different seasons, human moods and emotions and those that celebrate nature. A traditional night would begin after sunset and go on till wee hours of the morning. The trend of music in the night is mostly associated with Hindustani or north Indian classical music.

Both north and south Indian classical systems originated as art forms in temple traditions. Music was an integral part of temple rituals and offered to gods. However, after Muslim invasions when temples were broken and plundered, the art forms of music and dance slowly migrated to royal courts. Finding patronage of royal kings, the art forms survived through centuries.

While that being the case in history, we have several treatises on music that have come down centuries listing series of Ragas and Raginis for a night. The ‘Sangita Makarandah’ of Narada II states that “One who sings knowing the proper time remains happy. By singing Ragas at the wrong time one ill-treats them. Listening to them one becomes impoverished and sees the length of one’s life reduced” (SM.I.23/24) Famous musicologist and scholar Alain Danielou writes “the cycle of the day corresponds to the cycle of life which also has its dawn, its noon and its evening. Each hour represents a different stage of development and is connected to a certain kind of emotion. The cycle of sounds is ruled by the same laws as all other cycles. This is why there are natural relationships between particular hours and the mood evoked by musical modes.” And this gets more pronounced in later treatises of music which classify Ragas of the day and night.

In the Carnatic system of music, this classification does not exist. For the sheer reason that this system evolved and was nurtured by temple traditions. Music and dance were regular offerings to god. And artistes from traditional performance practitioner communities were dedicated to temples for this purpose. The iconic Brihadeeswara temple in Thanjavur once had over four hundred artistes dedicated to the service of the lord. As per temple timings, they are closed by night. Even the last of the poojas does not reach the midnight hour except on special occasions. So music and dance being a part of ritual offerings were never outside of the temple space. So was the content in these art forms. Which is why you find Carnatic music full of songs in praise of gods. It was much later that the same music made its way to royal courts, like it did in north India.

However it was limited and the essential core of Carnatic music, which is Bhakti or devotion, didn’t change. Carnatic music in royal courts was just another extension of what was sung in temples. It was only after the Vijayanagara Era that we find songs in praise of local kings. These were mostly written by court musicians and performed by court dancers on special occasions like birthdays, commemorative days and for royal guests. Therefore the concept of having a special music or Ragas for the night does not exist in this ancient system. It is only in much later centuries that few Ragas migrated from the north to the south and vice versa.

The night in the Hindustani system is divided into several ‘prahars’. 8 PM to 10 PM is classified as ‘late evening’. Night begins from 10 PM up to 12 midnight. Midnight lasts from 12 to 2 AM. From 2 AM to 4 AM, it is pre-dawn. So the hours after sunset or dark are divided into set of four. Most Ragas have been fit into these sets over the centuries. For easy understanding, we can call them Ragas of the early night and late night. In Hindustani music, the Kalyan family of Ragas belongs to the early night. They include Yaman Kalyan, Tilak Kamod, Yaman, Chhayanat, Kedar, Bhoopali and so forth. The first quarter of the night has Ragas like Durga, Hameer and Khamaj. The second quarter of the night has Ragas like Suha, Sahana, Bahaar, Jaijaiwanti, Bageshri, Kanada, Kafi and Suha. The late night Ragas come with a different set of moods. Ragas like Malkauns and Bihag are classified in the midnight category. After midnight we have Ragas like Paraj and Shohini. As the night comes to an end, we find Ragas like Shankara and Kalingada in the hours before dawn. The list has grown exhaustive over the years. Many music maestros have also experimented with Raga scales and created their own melodic structures and fit them into the traditional time cycles.

Pandit Vishnu Narayana Bhatkhande (1860-1936), one of 20th century’s most eminent musicians, musicologists and writers has done a detailed study on the technical nuances of the Ragas that must be presented at night. His theory argued that Ragas were classified into families or ‘Thaat’. Every Raga belonged to a certain Thaat. Each Thaat had its own specialty. In his exhaustive research, one finds Raga scales with certain notes predominant to elevate mood swings are highlighted. The same mood can be seen in the visual representations of Ragas. Over the years, many ‘Raga Chakra’ charts were designed, more to make a student of classical music understand the theory, as a part of his music education.

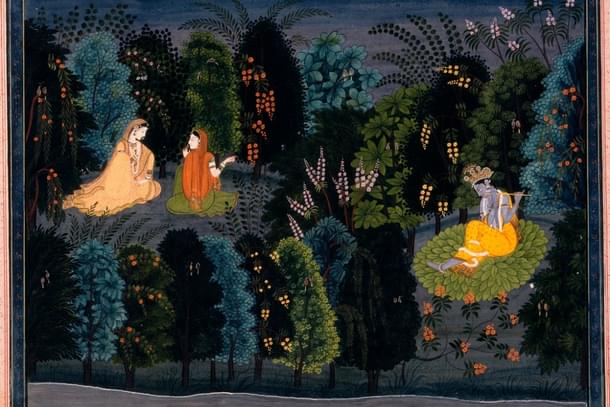

The Ragmala paintings comprise a whole different world on their own. A wonderful phenomenon of commissioning court artists to depict Ragas was a practice in several North Indian Kingdoms. This furthered the cause of the various traditional schools of Indian art and painting. So aross North India, we have schools like Chamba, Basholi, Kangra, Mewar, Daccani, Rajput, Pahari and many traditional schools of paintings that flourished. We find all of them have attempted at depicting Ragas and Raginis through their own style. They have also portrayed the various Nayikas as detailed in treatises of dance like Natya Shastra and Abhinaya Darpanam. Many times we find a combination of the two schools merging in thought and being actualized on canvas. So you can find a night Raga being portrayed through the mood of a Nayika Bhava. Take for example the ‘Shuklaabhisarika Nayika’. Here she is depicted as one who goes out to meet her lover on a moonlit night. The moon has grown pale with shame at the lovelier brightness of her face. The Chakora birds have also forgotten the moon for a while and are looking at her. Guru Gobind Singh in the Dasham Granth described the Nayika as Radha with a beautiful poem.

‘Chhaki Prema Nema Mein Chhabili Chaila

Chhaila Ki Basuriya Ke Chhalan Chhali Gayi

Gahire Gulaban Ke Gahire Garoor Gare

Gori Ki Gandha Gail Gokul Gali Gayi.

Darr Mein Dareen Hoon Me Deepath Divaari Dari

Dant Ki Damak Duti Damini Dali Gayi

Chausari Chaveli Chaaru Chanchal Chakoran Se

Chandni Me Chandramukhi Chaunkath Chali Gayi,’

Meaning

‘The beautiful Nayika rapt in love,

Hears the call of the flute of her lover and goes out to meet him.

She is lovelier than the rose,

And her fragrance fills the streets of Gokul as she walks.

Her beauty shames the lit lamps,

And the sparkle of her teeth dims the flash of lightning.

The moon-faced Nayika with eyes more restless than the chakora’s

Moves on through the moonlit night’

If you see this exquisite depiction in the poem and the painting associated with it, you are bound to think up the moon in which this situation could be possible. A serene sense of music accompanies that mood. The same poem has been sung by several Hindustani maestros in various Ragas of the night going by the mood of the subject. These poems along with Ragas also become able canvasses for Abhinaya or aesthetic mime in the classical dance traditions. We have seen several great dancers performing to these beautiful lines. This way we have a whole long list of Ragas and Raginis visualized in the north Indian miniature art tradition. There are also Ragas for different human moods and emotions in different seasons. But that is another long story for another time.

In the end the entire theory of Ragas and Raginis associated with a particular time, rests on the shoulders of the performing musician. An ace maestro can perform any Raga at any time of the day and elevate your mood. Try locking yourself up in a room in the afternoon and listen to a late night Raga like Darbari Kanada or Sohini rendered by maestros like Pt Bhimsen Joshi or Vidushi Kishori Amonkar, you will actually feel that it might be a midnight hour. This subtle experience of mood change comes from the music rendered. Someone making bad music can ruin any mood at any given time of the day or night. To do intellectual justice to the rendering of a Raga and elevate its mood to bring about the true Rasa, rests on the performer as well as the well-informed and highly receptive Rasika. If the performer is excellent but the audience isn’t receptive or intelligent to understand the music, it is a wasted effort. Similarly the other way round. This is one of the reason, Indian classical music is for the informed Rasika whose sense of aesthetics is several notches above the layman. The act of making and listening to classical music are equally demanding on the performer and the listener. To achieve the desired wholesome aesthetic experience, or the ‘Rasanubhava’, there are no shortcuts.

For a regular performer and a regular listener, the Ragas of the day or night wouldn’t matter because the experience of Rasa overshadows technical demands of performance. To experience the feeling of night in melody or melody in the night, you should be receptive to the ideas both want to convey to you as a Rasika.

Veejay Sai is an award-winning writer, editor, columnist and culture critic. He has written and published extensively on Indian classical performing arts, cultural history and heritage, and Sanskrit. He is the author of 'Drama Queens: Women Who Created History On Stage' (Roli Books-2017) and ‘The Many Lives of Mangalampalli Balamuralikrishna' (Penguin Random House -2022). He lives in New Delhi.