North East

When Memory Is All That Remains Of The Charm Of Northeast's Old Colonial Towns

Nabaarun Barooah

Jul 13, 2025, 07:30 AM | Updated Aug 03, 2025, 09:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

It begins with a quiet drive through the narrow lanes of Uzan Bazar, Old Gauhati (not Guwahati), just after the rain. The road glistens beneath soft streetlamps, and I notice the remains of an old Premier Padmini ahead, its white paint dulled by time. It reminds me of the car my grandfather owned, driving us through the small town.

To the left, the hundred-year-old trees of Dighalipukhuri form a canopy so thick they seem to bend the sky. The breeze carries the faint rustle of bougainvillaea brushing against tin roofs and the faraway chime of the evening aarti from Ugratara Shaktipeeth.

I know this road. Near my house, by the corner bookshop with yellowing shelves, I once waited under an old tree for a bus that never came. My grandfather used to speak of the same tree when he was a boy, how its red petals would carpet the earth before Bohag. Nothing monumental ever happened under that tree, which is precisely why I remember it.

Time in these parts is not measured in buildings but in routines: the call of the fish seller at 7 a.m., the shopkeeper who still wraps packets in old newspapers, the uncle with the same moustache and crossword addiction since 1997. These are the cadences of a city with memory.

And yet, I recently read a piece by my friend Janak describing Guwahati as a modern city, tasteless, chaotic, ambitious, a concrete bazaar inflated by sudden prosperity. None of it is untrue. Flyovers sprout overnight. Cafés sell tiramisu with ghee. The skyline mutates faster than the seasons. But that city, the new Guwahati, is only half the story.

This is the other half. Gauhati, not Guwahati. The one that I belong to. The one being erased. The chaotic rise of new Guwahati has painfully suppressed the old one. This piece is an act of remembering, of placing my hand gently on the older city’s shoulder and asking if it still remembers me too.

The Quiet Elegance of Forgotten Towns

Unlike Guwahati, Gauhati doesn’t announce itself. You don’t arrive at it, it arrives through you.

Sometimes in a gust of cool wind off the Brahmaputra as you stand near the Kharghuli hills at dawn, the city still hushed, the water turning silver. Sometimes in the silhouette of a fisherman casting his net where there should have been a promenade but thankfully isn’t.

These neighbourhoods, Uzan Bazar, Panbazar, Kharghuli, were not designed as destinations. They were just places where people lived, prayed, quarrelled, aged. Where the river was not yet a 'riverfront attraction' but a constant presence, eternal, unadorned, sacred.

There were mornings when I would cross to Panbazar on foot, buying a newspaper from a man whose son now runs a cyber café. He still remembers my name. At a time when most cities are becoming forgetful, that alone feels like a kind of miracle.

The old homes here breathe slowly, some with rusting iron gates, some with wooden windows painted blue and green, colours now faded like the memories they frame. They have withstood not just time, but indifference.

Shillong, the capital of Assam before 1972, had its own kind of hush. A Calvinist calm seemed to ride the pine-scented air. Dhankheti, Laitumkhrah, Laban, Nongrim Hills, they weren’t grand, but they carried themselves with grace.

The homes looked like they had been plucked out of some quiet English countryside and forgotten here, tucked into the hills. Wooden stairs creaked politely. Front yards wore moss like velvet. The rhythm was slow, but never sleepy.

When I visited Shillong as a child, I would sit by the bay windows of a tea stall in Nongrim Hills and watch the rain thread itself into the mist. The owner, a lady, would play jazz records in the background, Coltrane, I think, and offer me lemon tea in thick porcelain cups.

Outside, children cycled downhill in school uniforms too large for their growing limbs. The postman still came on foot. There was another woman who baked cakes for half the neighbourhood, she remembered birthdays better than anyone else.

These were towns that wore the dignity of memory. They didn’t strive to be cities. They never needed to. In some ways, they were more complete for it.

Now, when I return, I still see traces of that world. But they are fainter. You have to look harder. The pine trees are crowded by cellphone towers. The baker’s house is now a Korean café. But the wind, sometimes, still smells the same.

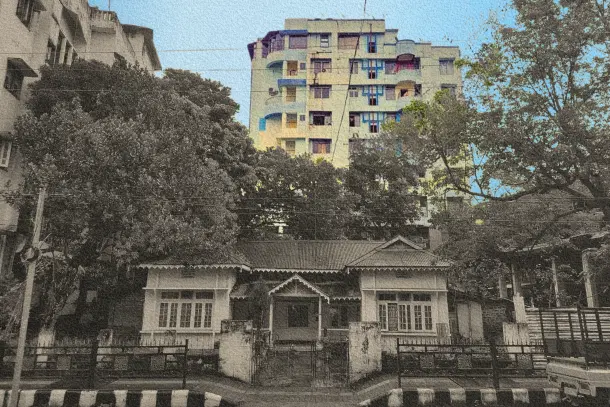

What set the old quarters of Gauhati and Shillong apart were the homes, those gracious, stoic Assam-type houses that seemed to belong more to the wind and rain than to concrete and road.

You could spot them tucked behind bamboo fences, painted in warm white limewash, their sloping tin roofs gleaming after a sudden downpour. In summer, they blazed with bougainvillaea, cascading pinks and oranges tumbling over gates, brushing against postboxes with names still etched in English, the lingua franca of old towns in the Northeast.

These weren’t mansions. But they had proportion and purpose. Wooden verandahs wrapped around them like shawls. Inside, the rooms breathed, a stillness broken only by the creak of polished teak floors or the clatter of cups during morning tea.

The ceilings were high, the air cool even in May, and the windows opened wide, not to balconies or ledges, but to actual views: of jackfruit trees, of hills beyond, of skies without wires.

Every house had a lawn, not manicured, but lived in. A hibiscus bush here, a guava tree there, always a bench for grandparents and guests alike. Nothing was crowded. Even the hedges gave you space.

The city layout mirrored that same sense of grace. Gauhati was square in its logic and gentle in its ambition. Roads criss-crossed at right angles, linking neighbourhoods like threads in a loom. You could walk from the bookshop in Panbazar to the riverside in ten minutes, stopping along the way at a sweet shop, a cobbler, and maybe someone you knew. The pavements weren’t perfect, but they existed. They were made of stone, not advertisement.

Shillong too had a human rhythm. Its winding roads didn’t follow an engineer’s command but the contours of the hills. You could walk from Don Bosco Square to Laitumkhrah without once feeling the need for a car. The shops had names that made sense. No 'Fusion Hut' or 'Pegasus Crown'. Just 'Paul’s Bakery', or 'Sangma & Sons'. Or even colonial names such as La Chaumière or El Dorado.

There was no gated community, because the whole town felt like one.

Today, it’s hard to explain to someone who’s only known the new GS Road stretch or the prefab apartment blocks near Khanapara what an Assam-type house meant. Or what it felt like to walk through a city not at war with itself.

They call those houses inefficient now. “Hard to maintain.” “Too much land.” “Good for a café maybe.” And so one by one, they fall. Replaced by concrete boxes, airless, identical, temporary in their ambition and permanent in their ugliness.

But for those of us who grew up watching light fall through cane blinds onto wooden floors, who remember the smell of wet earth after an afternoon storm, they are not just houses. They are time.

And it is running out.

The World Arrives: Progress Without Soul

The first cracks didn’t come like thunder. They came as whispers.

It began with a mall in Christian Basti. Nothing extraordinary, just a slab of glass and steel announcing air-conditioning and global brands. Then came another, and another. And before we could name what we were losing, GS Road had turned into a corridor of ambition.

A place once dotted with green fields and wetlands now bristled with clinics, co-working spaces, and the latest “sky-view” restaurants selling ₹800 pasta to people who had never eaten a proper aloo pitika outside home.

In Shillong, Khyndailad, what we once called Police Bazaar with fond irritation, was the first to buckle. Today, it groans under the weight of taxi horns, Instagram tourists, and cafés serving “Naga fusion momos.” You see rows of selfie sticks, not pine trees. You hear Bluetooth speakers, not the hush of wind through fir needles. There’s no space to pause. There’s no silence to hear yourself think.

Of course, some of this change was inevitable. The cities had begun attracting people in greater numbers: students from Nagaland and Manipur, bureaucrats from Delhi, labourers from Bihar, unemployed youth from Upper and Lower Assam, migrants from Bangladesh, and developers with PowerPoint decks and “vision plans.”

They come hungry and hopeful, but also impatient, entitled. Where the old city would negotiate gently, the new shouts to be heard.

Everyone brought something new. But in their coming, something old had to leave.

The transformation of a city is not just in its skyline, but in its soundscape. In Guwahati, the noise has changed. SUVs with tinted windows barrel down lanes that once barely fit Maruti 800s. The air trembles with bass-heavy Punjabi music, on weekends, but increasingly on weekdays too. Number plates from neighbouring states flash past in convoys. Loud voices spill out of open windows. Confrontation is casual. Volume has become culture.

But Gauhati’s voice was gentle. Old-timers nodded instead of waved. Disagreements were folded into jokes, resolved with a second cup of tea. The city had the manners of its climate, humid, quiet, and polite even in discomfort.

Now, the air of Guwahati is louder, more confrontational. The new occupants speak with urgency, often with aggression. They are not necessarily outsiders by geography, but by sensibility. Even at Uzan Bazar, where I live, where old Gauhati still lingers like perfume on ageing fabric, the sounds are different. Someone is always selling something. Someone is always shouting.

I don’t resent it. I understand it. The city is growing. But it grows like a child in shoes too tight, awkwardly, impatiently, without grace. And in this hurry, something is being erased.

I remember the first time I saw a colonial bungalow in Silpukhuri being fenced off. I was still in high school. The house had stood under a canopy of mango trees, with green shutters and a nameplate faded by three generations of sun. Within months, it was rubble.

A four-storey café-cum-co-working space-cum-gym now stands there, draped in fairy lights and pretension. The owners, descendants of the old family, had no choice. “Property tax was bleeding us,” one had said. “At least now we can visit it as customers.”

A few lanes away, in Panbazar, there used to be a woman who ran a tiny lending library. No more than three shelves in her drawing room. She knew our names, our tastes, and often tucked in a handwritten note with the book we borrowed.

That house is gone too, sold off to a builder from outside who never lived there. Her library was scattered, her stories unread.

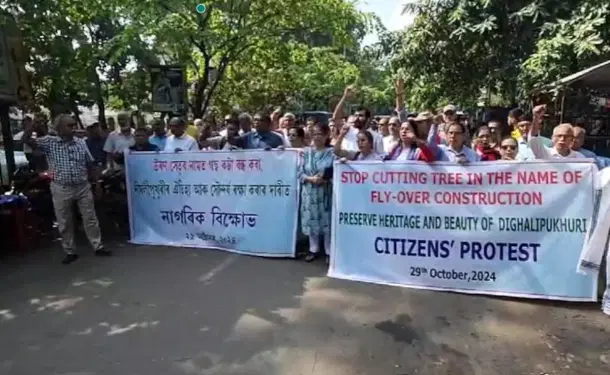

The trees are casualties too. The ones that lined the riverside near Sukreswar and Fancy Ghat? Gone. Contractors come at night. Permissions arrive after the fact.

Even the tall gulmohars and cherry trees in Shillong, the ones that bloomed like a flame each April, they are now hemmed in by a hotel’s generator shed. Someone files a petition. Someone else shrugs. By morning, there’s a new board promising a “Smart City.” By evening, the roots are dust.

I sometimes wonder when we stopped noticing.

Was it when flyovers became the measure of progress? Or when we accepted parking lots as replacements for parks? Or when every other house hung a “To-Let” sign for office space instead of looking for tenants to share stories with?

Perhaps the worst part is that we’ve stopped resisting. We call it development, even when it has no soul.

The Lost Art of Serendipity

There was a time, not so long ago, when you could set out from home with no destination in mind and still return full: full of stories, of songs, of smells you did not expect but now cannot forget.

In Old Gauhati, you could walk from a bookshop in Panbazar to the banks of the Brahmaputra in less than ten minutes, stopping at a momo stall, a record shop, and the rickety staircase of the College Studio on the way.

You would run into someone from school, an uncle who once taught you chess, a woman who sold apples and remembered your name. The city breathed in your rhythm. It did not jostle you forward; it walked beside you.

Even Shillong, in its quieter quarters, had this accidental grace. You would leave Laban to return a library book, turn a corner in Malki, and find a music teacher rehearsing Chopin with her windows open. You did not need a playlist. Cities like these offered one.

That spontaneity is gone now.

The pavements are gone too. Literally. Footpaths have been swallowed by bike showrooms and parked SUVs, by roadside signage and advertisement hoardings offering Korean skincare or luxury hostels.

In Guwahati, the new riverfront and Heritage Centre is less a place to think and more a venue for concerts and cables. You need a ticket to find quiet now.

In cities that breathe, you stumble upon joy. But ours have stopped breathing.

Gauhati and Shillong once gifted you the magic of the unexpected: watching kites rise over the Raj Bhavan lawns, hearing a sarangi on the radio drift out from a tearoom, spotting a hand-painted film poster taped to the back of a bus.

Today, everything is curated, scheduled, pruned, and optimised.

Even conversation has retreated indoors. Where once shopfronts buzzed with gossip, you now receive transaction slips and silence. People talk less. They scroll more.

The neighbourhood café no longer keeps an ashtray on the outer sill, where someone’s grandfather once sat, sipping lal sah and yelling cricket scores into the street.

We have lost the pleasure of being surprised by our own city.

I miss walking without purpose. I miss bumping into someone I did not plan to meet. I miss places that were not marked on Google Maps.

I miss visiting the riverside without having to pay a ticket price to enter a government-operated riverfront.

But more than all that, I miss the feeling that a city could still gift you something, unasked and unearned, simply because you lived in it.

The recent development and migration would be tolerable if it still allowed room for serendipity. The chance discovery of a momo stall behind a temple, the impromptu concert by an uncle’s Spanish guitar on the riverbank, the smell of fresh ink at a neighbourhood press.

But now, even spontaneity is scheduled. Cafés have calendars. Riverfronts host laser shows.

And so, the soul recedes.

Memory as Resistance

I have come to believe that remembering is a political act. Especially in cities like ours, where change is sold as destiny and forgetfulness is built into policy.

No, I do not wish for regression. I do not want to live in the past, nor do I believe that nostalgia is enough. But I do believe that memory has muscle. It can resist. And sometimes, in small corners of Gauhati and Shillong, it does.

Like at Tea Story in Uzan Bazar. In that Assam-type bungalow, the lighting is dim, not because they cannot afford LEDs, but because they choose to keep the amber glow. The walls are not distressed for aesthetic reasons; they are simply old. Nobody rushes you.

Or Dylan’s Café in Shillong, which still plays classic rock and keeps a section of its walls for vinyl records, something still found in old homes of a city increasingly falling prey to loud rap songs blasted by SUVs.

In Guwahati as new flyovers come up, a quiet aesthetic revolution unfurls as plain grotesque streetlights are being replaced by classic ones. Maybe there is some semblance of beauty after all.

In Panbazar, Modern Book Depot still opens late but never forgets a name. You go in for a book and come out having discussed Hem Barua or Pablo Neruda. It is not just a shop. It is a quiet outpost of memory.

These places resist not through activism or confrontation, but by continuing. They insist on being what they were, even as everything around them changes.

They remind us that cities are not just made by mayors and engineers, but by barbers, grocers, librarians, and waiters who remember your order even when you forget your wallet.

To refuse the new is not always to be stubborn. Sometimes it is simply to be faithful. Faithful to a rhythm, a texture, a soundscape that does not show up on spreadsheets but lingers in the mind like a familiar song.

I know the builders and contractors will win. They always do.

But I also know that somewhere in Kharghuli, there is an old house with cracked verandas and a loyal dog, where the walls still smell faintly of old newspapers and agarbatti. Someone still lives there. Someone still remembers.

And maybe that is enough.

A City That Still Breathes, Somewhere

It was a quiet evening not long ago when I took a walk down the familiar stretch between my home in Uzan Bazar and Raj Bhavan. The light was just beginning to fade behind the hills across the river.

The trees are fewer now. Their shade has been replaced by signage. The road feels louder. The breeze more interrupted.

But then, a child cycled past me. Barefoot, shirt untucked, chasing a red kite that danced over a tangle of power lines. For a brief moment, the years collapsed.

Perhaps that is what cities do. They decay, regenerate, and sometimes forget themselves.

Maybe Gauhati and Shillong are like palimpsests: old texts overwritten, but not entirely erased. You have to squint to read the older script. But it is still there, beneath the flyovers and the malls and the new signage glowing in LED.

Cities do not die. They become something else.

But those of us who lived in them before the forgetting began, we carry their quieter names. We remember the footpaths that led somewhere. We remember the bougainvillea in front of Assam-type houses. We remember the silence between dusk and dinner, the sound of distant temple bells or a choir in rehearsal, and the odd stranger who smiled (and still does, assisted by a walking stick) simply because you passed them on a walk.

The new Guwahati may rise like scaffolding in a hurry. It may chase relevance, accumulate glass and cement, and drown in ambition.

But somewhere, in a house shaded by gulmohars or on a lane where time still limps instead of sprints, the old Gauhati waits, breathing, even if wheezing, and hoping not to be forgotten.

And as long as we remember it, perhaps it never really will be.