Politics

Borderlands Of Flux: Malda, Murshidabad, And The Vanishing Voter

Pulkit Singh Bisht

May 01, 2025, 04:21 PM | Updated 04:47 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Once upon a time, Murshidabad reigned as the cultural jewel of Bengal, the seat of Nawabs, home to regal palaces, silk traders, and the lyrical hum of poetry. Just to the north, Malda bloomed as a vibrant epicentre of mangoes, muslin, and constant movement. These two districts, flanking the porous Indo-Bangladesh border, were silent witnesses to the golden age of Bengal.

Today, that grandeur is archived. The identity of these districts is being redrawn through census data, migration patterns, and voter lists. What unfolds here is not just a tale of place, but a striking portrait of how shifting demographics can quietly reinvent the pulse of a democracy.

It all began in 1947. Partition sliced across Bengal like a jagged wound, forcing millions into a frenzied migration—Hindus fleeing East Pakistan, Muslims moving in the opposite direction. For a single day, Murshidabad was part of Pakistan. Then the lines shifted again, and it was pulled back into India. Malda, too, stayed on this side of the Radcliffe Line.

But Partition was merely the first chapter. The 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War sparked another exodus. What began as a trickle soon became a steady surge. While most of India saw a demographic settling after Partition, Murshidabad and Malda remained in flux, forever reshaped by invisible tides.

In 1951, nearly 44.6% of Murshidabad's population was Hindu. Today, that number has dropped below 35.12%. Muslims now form more than 63.67%, a steady rise driven by natural growth, alleged cross-border immigration, and the gradual exodus of Hindus who no longer feel secure in a once-shared land.

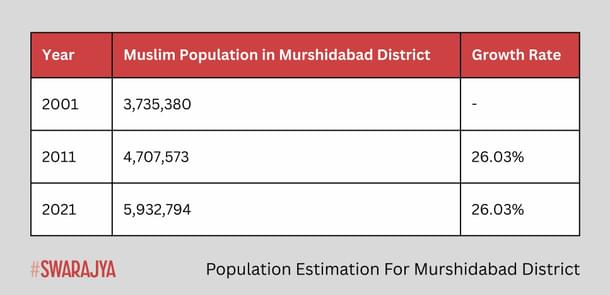

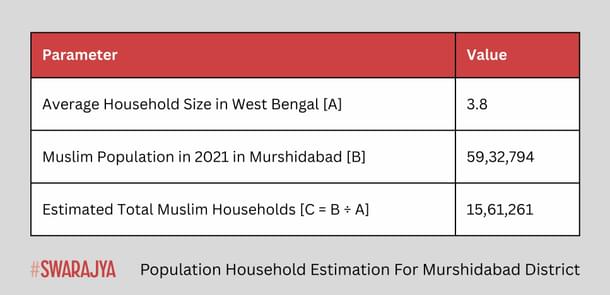

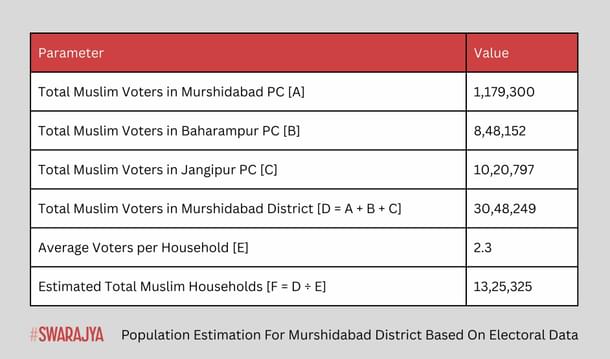

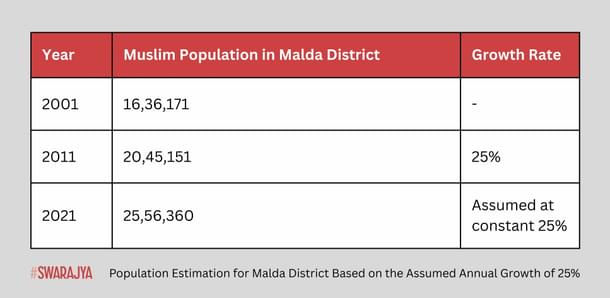

From 2001 to 2021, while census data suggests 15.6 lakh Muslim households, the voter rolls registered only 13.2 lakh, leaving a mysterious gap of nearly 2 lakh families. Are these unregistered voters? Inflated population projections? This discrepancy raises questions about under-registration, data accuracy, or the possible presence of undocumented migrants.

Electorally, the district reflects this demographic tide. Since 2004, Muslim candidates have dominated both winners and runners-up in Lok Sabha elections, consolidating vote shares of over 40%. But the twist lies in their partial invisibility—powerful on the ballot, yet elusive on paper. That ambiguity lends itself to volatility.

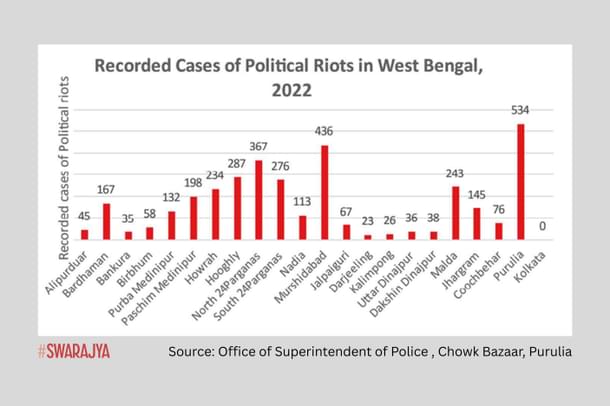

Murshidabad has become a powder keg. Protests erupt over laws like the Waqf (Amendment) Act, and communal tensions often spark headlines. Official reports suggest that illegal immigrants are sometimes behind the unrest, pushing out local Hindu families. Without voter IDs but with mobilisable strength, these invisible residents become loud voices in turbulent times.

![Samshergunj [2014 (left) and 2022 (right)]](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2025-05-01/fx97t578/146.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

![Jhangirpur [2010 (left) and 2017 (right)]](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2025-05-01/je489915/145.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

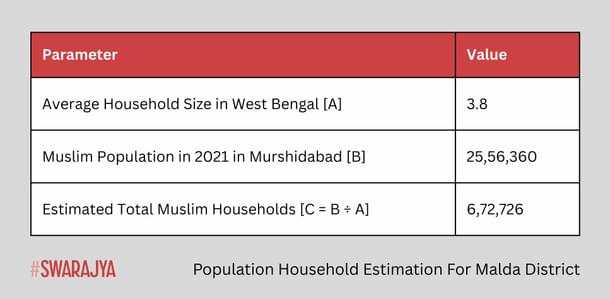

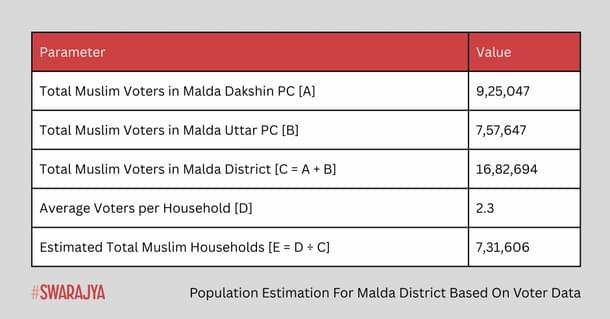

North of Murshidabad, Malda tells a different story. It’s not where people settle—it’s where they begin their journey. Stretching along a 170-km unfenced border, Malda is India’s backdoor. But its demographics are harder to pin down. Between 2001 and 2021, its Muslim population leapt from 16.3 lakh to 25.5 lakh. Yet here, voter rolls oddly overestimate Muslim households compared to projected population figures. Why?

Because people from Malda are constantly leaving. According to the Economic Survey of 2016–17, it’s one of India’s top districts for outmigration. Floods, poverty, and unemployment push men out to Delhi, Bhadohi, and Aizawl in search of work. Their names remain on voter lists back home, long after they've gone.

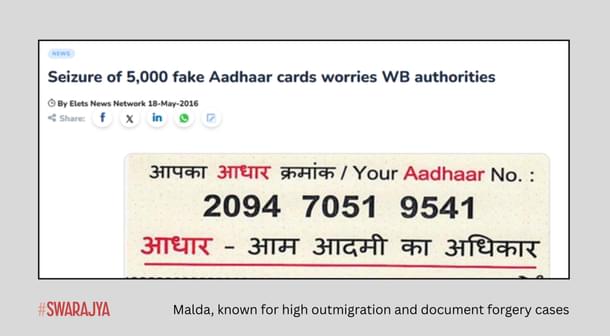

Another layer muddles the waters: document forgery. In Malda, fake Aadhaar and EPIC cards are available for ₹400. Entire racketeers manufacture bogus papers, making Malda a launchpad for illegal entrants. In one village alone, over 5,000 fake Aadhaar cards were seized in 2016. This contributes to inflated voter rolls padded with real migrants and fictional identities alike.

So we see two faces of the same geography.

Murshidabad—a destination for settlers, a strategic voting bloc, yet with portions of its population fading from formal records. A place that simmers with political energy, waiting for a spark.

Malda—a departure point, a migrant’s first stop. It’s not about the vote, it’s about documentation, passage, and dispersal into the nation’s veins.

Together, these districts form the hidden gears of West Bengal’s democratic engine. But they also reveal a deeper national story—one where borders are not static lines but shifting tales of people, paper, and politics.

As India grapples with the thorny debates around illegal immigration, electoral fraud, and border control, Murshidabad and Malda remind us that democracy is never just about casting a ballot. It’s about who is seen and who is not—because somewhere in Bengal, at the next election, a vote may be cast on behalf of someone who left long ago… or someone who was never meant to be counted at all.