Politics

What The Congress May Be Trying To Pull Off In Bihar

Abhishek Kumar

Feb 12, 2025, 05:20 PM | Updated 10:06 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

On 5 February, 2025, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi made a visit to Patna, Bihar. The highlight of his visit was paying respect to Dalit icon Jaglal Chaudhary on the latter's birth anniversary.

Chaudhary was a freedom fighter and an anti-discrimination activist. Born in Saran, Bihar, Chaudhary belonged to the Pasi community (the same as Chirag Paswan). He left his medical studies to join the independence movement and later participated in the Non-Cooperation Movement, Salt March, and the Quit India Movement, among others.

Chaudhary and Dr Rajendra Prasad, India’s first President, shared cordial relations. Chaudhary was the first minister in Bihar to implement a liquor ban in five districts of the state, even though the community to which he belonged used toddy as a chief source of income.

He was the first Dalit Cabinet Minister of Bihar and a vocal supporter of Dr Ambedkar. He also wrote a book titled A Plan to Reconstruct Bharat, aimed at eliminating social and religious discrimination.

An event in Chaudhary’s remembrance was organised by the Bihar Pradesh Congress Committee (BPCC) at Patna's Sri Krishna Memorial Hall. During his address, Rahul Gandhi seemed unaware of Chaudhary’s contributions. He mispronounced Jaglal as Jagat Chaudhary thrice and corrected it after the audience pointed it out.

Gandhi raised the issue of Dalits not getting proper representation and asserted that Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) give Dalits representation only in name and not in a participatory manner. Focusing on his caste census demand, Gandhi criticised the Modi government for not being serious about it.

“While speaking in Parliament on Tuesday, I talked about technology and also talked about the participation of Dalits, backwards, and tribals. I also reiterated the demand for a caste census,” said Gandhi.

The event, however, drew significant criticism for being a 'politically motivated exercise' which too was not executed properly. Chaudhary’s son, Bhudev Chaudhary, was not given a proper invitation to the event. Despite that, he attended the congregation but was neither given a place on the dias nor allowed to meet Rahul Gandhi.

Reacting to the development, BJP spokesperson Arvind Singh said that neither Rahul Gandhi nor the Congress—from Nehru to Sonia Gandhi—ever respected Dalits, backward classes, or extremely backward classes. He also alleged that Rajiv Gandhi used the term “illiterate” for the Dalit community when the question of their representation was raised.

Meanwhile, JD(U) spokesperson Neeraj Kumar questioned the timing of Gandhi’s speech. Kumar claimed that Congress ignored Chaudhary’s legacy for decades and that it was Nitish Kumar’s government that installed his statue in Kankarbagh, Patna and that during Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government, a postal stamp was issued in his name.

When the issue of disrespecting Bhudev Chaudhary grabbed headlines, Bihar Congress distanced itself from the event, claiming it only played the role of facilitator and not was not the organiser.

But 5 February was not the first time that Rahul Gandhi had gone to Bihar in recent weeks. On 18 January, 2025, Gandhi arrived in Patna to attend a “Samvidhan Suraksha Sammelan”. The hotel where Gandhi stayed was also occupied by Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) leaders for their national executive meeting.

Gandhi met Tejashwi Yadav and later visited his home for a 20-minute snack break, where he was greeted by Lalu Yadav and other family members.

Despite these pleasantries, Gandhi did not hesitate to take on Tejashwi himself. During his address to the Sammelan, he termed the Bihar caste census—conducted when Nitish Kumar had joined hands with RJD—as fake, asserting that Congress would initiate efforts for a nationwide caste census.

Ironically, Congress had endorsed the survey too.

But Gandhi and the Congress in Bihar do not seem to have the time for factual details right now. Their challenge is much bigger.

To begin with, the Bihar unit of the party needs to assert itself more firmly in the seat-sharing talks with RJD for the Assembly elections due in Bihar later this year.

The fact that Congress did not field Kanhaiya Kumar and distanced itself from Pappu Yadav’s Lok Sabha candidacy speaks volumes about RJD’s influence on Congress’s decision-making. Lalu Yadav sees both these leaders as threats to his son’s chief ministerial ambitions.

Congress does not want a repeat of the 2015 assembly elections and Lok Sabha elections of 2019 and 2024, where it thinks it got far fewer seats to contest that it deserved. For that, it needs to consolidate a vote bank, just as RJD has with its Muslim-Yadav (M-Y) base. For Congress, this would mean returning to its decades-old style of politics in Bihar.

Three pillars of Congress domination in Bihar

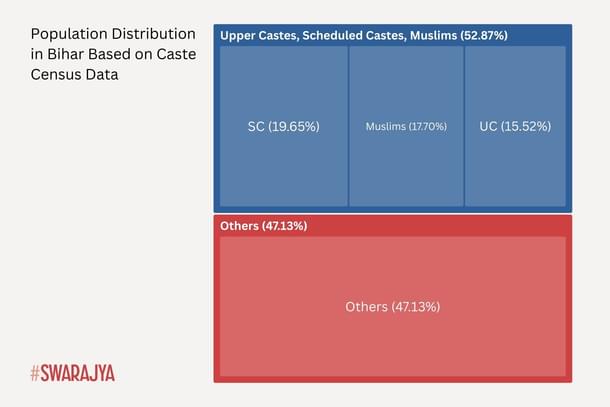

Till 1990s, the party dominated Bihar’s political spectrum with help of 'upper castes', Muslims and Scheduled castes.

According to the latest data available from Bihar’s caste census, the 'upper castes' comprise of 15.52 per cent of state’s population. The corresponding figures for Muslims are 17.70 and 19.65 per cent respectively.

Together, these three groups give any political parties leverage over nearly 52 per cent of total votes.

Congress’s history in Bihar has been glorious. Even though RJD and Janata Dal (United) (JD(U)) have shared the state’s power landscape for the last 35 years, they have still not come close to the dominance Congress once held.

Before Lalu Yadav came to power, Congress was the dominant force Bihar for more than four decades and gave the state 14 chief ministers—who ruled across multiple timelines.

Most of these chief ministers were from the 'upper castes', with Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal of Mandal Commission fame and Abdul Ghafoor being notable exceptions. In fact, with less than 20 per cent of the population (reverse extrapolation from the recent caste survey in Bihar), the 'upper castes' commanded over 40 per cent of legislative assembly seats on Congress tickets.

They not only held the highest positions within the government but also dictated the direction of state policies. Even in non-representative posts, such as memberships of the Congress Working Committee and Pradesh Congress Committees, 'upper castes' dominated the roster.

This dominance is evidenced by five chief ministers from the 'upper caste' category in the last decade of Congress rule in Bihar.

Among Hindus, Dalits acted as another pillar of Congress’s support base in Bihar—although not as rigid as that of the 'forward castes'. When it comes to Dalits, Congress mainly benefited from its overall dominance in the Indian political space.

Initially, it was seen as the only party capable and powerful enough to ensure constitutional safeguards of reservations and other egalitarian provisions in the country—and by extension, the state.

Congress did provide representation to Dalits, but barring exceptions like the elevation of Jagjivan Ram as Deputy Prime Minister, the representation is today seen as tokenism.

The party’s Dalit support base started to drift away the late 60s onwards, and this topsy-turvy relationship continued with few blips till the late 80s.

The emergence of Dalit leaders like Ram Vilas Paswan, combined with aggressive movements against 'upper caste' dominance, led to the decline in the Dalit support base of Congress.

The third pillar of Congress’s dominance in pre-1990 Bihar was the Muslim vote bank. Congress managed it through its image of being the most 'secular' political front. The threats of communal disharmony helped consolidate the Pasmanda vote bank, while Ashrafs, including Syeds, Sheikhs, and Pathans, ruled from the top.

Leaders like Abdul Ghafoor, who served as Bihar’s Chief Minister from 1973 to 1975, played a vital role in maintaining Muslim support. However, communal incidents leading up to the 1989 Bhagalpur riots sowed seeds of discontent, which later set the base for regional parties replacing Congress’s hold on Muslim voters.

By 1990, Lalu Prasad Yadav came to power and changed Bihar politics.

Simultaneously, Muslims were not happy with Congress due to the Bhagalpur riots, while 'upper castes' did not see their future in a party that had plateaued in the state.

Lalu Yadav projected himself as a champion of not only those near the bottom of caste hierarchy but also of the poor—from the economically weaker 'upper castes' to Dalits. Simultaneously, he also came across as a vociferous opponent of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement—going as far as arresting Lal Krishna Advani during the Rath Yatra.

In essence, he took away two of Congress’s three vote banks in Bihar—the Dalits and Muslims. The 'forward castes', the third vote bank and probably the key to this combination, now saw both Congress and Lalu Yadav antithetical to it, so they needed a third front. This was the BJP.

The decline of Congress dominance in Bihar

Between 1985 and 1995, Congress’s seat share in the Vidhan Sabha of undivided Bihar tanked from 196 to 29. Its vote share went down from 39.30 per cent to 16.30 per cent.

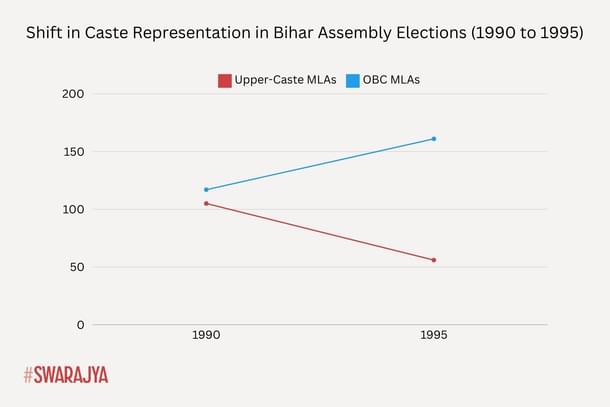

Simultaneously, the caste composition of legislators in the Bihar Assembly was changing too.

For instance, in the 1990 Bihar Assembly Elections, there were 105 'upper-caste' MLAs, while the number of OBCs was 117. Within one election cycle, 'upper caste' legislator figures came down to 56, while the number of OBC MLAs shot to 161.

Many old-time political observers believe that close to 70 per cent of the total Muslim votes—erstwhile understood to be with Congress—had also transferred to Lalu Yadav by 1995, but any data on it is not available in the public domain. However, by 2000, that transfer was more obvious, and Congress had no option but to surrender itself to the whims of Lalu Yadav and his RJD.

Scattering of Congress' vote bank

It has been straight downhill for Congress after that.

Lalu Yadav effectively became the decision-maker for the Congress in Bihar, and his interest aligning with Congress’s decline meant that the national party was bereft of options.

If it did not contest as an RJD ally, Congress had virtually no standing on its own; but if it did, then Lalu Yadav would distribute tickets in such a way that the Congress would get minimal seats.

Resultantly, the party’s performance over the years showed a persistent decline. Between February 2005 and November 2020 AE, the party tried to get on its feet, but has been inconsistent - primarily due to RJD not giving it ample space to expand.

For instance, in 2015 AE, the party bargained for more, but it was given only 41 seats to contest - possibly as a punishment for contesting all 243 seats in 2010. However, even with that, it secured secure 27 seats. The majority of tickets were distributed among the traditional vote banks of Congress, with 'upper castes' (40 per cent), scheduled castes (25 per cent), and Muslims (25 per cent) taking up 90 per cent of tickets.

RJD: Shackles and baggage

Their tenure in power cemented the image of RJD as a collective of people that can turn into anti-social elements at the slightest provocation or incentive. This atmosphere was seen on roads as well as in political rallies.

Increasing crime and decreasing human development indices put off many voters, including those from the backward classes, and they had to look for a new leader. That is where Nitish Kumar came with his appeal for development.

His promise to end crime resonated with every section of society. Nitish Kumar’s government implemented several initiatives targeting Dalits, particularly by creating the "Mahadalit" category, which included 23 out of 24 Dalit sub-castes, excluding the influential Paswan community.

A Mahadalit Commission was established to address the needs of these marginalised groups, with land allocation being a key focus. Each Dalit family was granted three decimals of land, although critics, such as Ram Vilas Paswan, dismissed this as insufficient and problematic.

To promote education, the state offered Rs 10,000 to Dalit students who passed their exams in the first division. Kumar also introduced 18 per cent reservations for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in panchayat bodies, leading to the election of over 1,400 Dalit mukhiyas.

Kumar was able to penetrate into the Dalit community votebank, while the BJP became the umbrella for the 'upper castes'.

As far as Muslim voters of Bihar are concerned, until the beginning of the 2020s, they kept oscillating between the JD(U), RJD, and sometimes Congress. When Nitish Kumar is with RJD, he gets Muslim votes, but when he is with BJP, Muslims generally have not been observed to vote for him.

Opportunity for Congress and feasibility

However, these two-decade-old patterns are in for a seismic shift in the coming years, signs of which are already visible.

Sections of the upper castes have been expressing unhappiness with both the BJP and JD(U) for more than a decade. Apart from development, their expectation from the alliance was the dilution of reservations and the curbing of the misuse of the SC/ST Act.

They allege that the BJP has failed them on both fronts and, to add insult to injury, the party has been promoting non-upper caste leaders for leadership positions.

Even though Vijay Sinha, one of the two deputy chief ministers, belongs to the Bhumihar community, the party is seen pushing another deputy chief minister, Samrat Chaudhary, as the leader of the party in Bihar.

With Kumar, the upper castes' main concern is his role in reviving RJD’s fortunes after the party was reduced to 22 seats in the 2010 Assembly Elections. Kumar’s constant flip-flopping does not help his cause either, as the upper castes fear a return to RJD’s ‘Jungle Raj’.

For Dalits, the 2025 Assembly Elections are likely to be the last election in which they vote in the name of Nitish Kumar. His stronghold on Dalit votes has already declined after 2015, thanks to his switching alliances and failing to improve upon the standard set by his own governance.

For Dalit votes, Jitan Ram Manjhi of Hindustani Awam Morcha (HAM) and Chirag Paswan of Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas) (LJP(RV)) have already established themselves as chieftains in their respective sub-categories of Musahar (3 per cent) and Pasi (less than 1 per cent) voters.

The Congress appears to be eyeing a space in post-Nitish Dalit politics where it is assuming that HAM and LJP(RV) will be main challenger for Musahar and Pasi votes while the space of other Dalit communities will be open for grabs. Although, it is not that simple until BJP contests with Narendra Modi’s face whose welfare programmes have helped garner support from Dalits.

Regarding Muslims, their political representation is at a very interesting crossroads. Even though RJD is known for its M-Y (Muslim-Yadav) strategy, in the last few years, Tejashwi Yadav has not been actively accomodating Muslim leaders in RJD’s decision-making structure. They are gradually disappearing from both RJD’s core leadership and cadre strength.

Yadav is also looking to expand his vote base beyond the traditional M-Y combination. His effort to bring Koeri-Kurmi voters into RJD has seen partial success, and now Muslims fear they will be sidelined in the long run.

Muslim voters also want to align with a party that has a higher winnability quotient. RJD’s decline and Muslim voters' loyalty to it over the last two decades has been crucial in their representation shrinking to less than 10 per cent in the Assembly. Given that Muslims make up 17.7 per cent of Bihar’s population, this figure is insufficient.

Another major concern is Yadav voters not supporting Muslim candidates during elections. In contrast, the reverse is true, as RJD tends to win Muslim-dominated seats by fielding Yadav candidates.

In the last three elections—2019 Lok Sabha, 2020 Assembly, and 2024 Lok Sabha—RJD fielded 23 Muslim candidates in total. Out of these, only eight won, that too only in the 2020 Assembly Elections. None of the six candidates secured victory in the Lok Sabha elections.

At Purnia Lok Sabha and Rupauli Assembly constituencies, Muslims ignored RJD’s appeal to vote for Bima Bharati. In Belaganj Assembly constituency, Muslim votes were split between JSP’s Amjad and AIMIM’s Zamin Ali Hassan.

While support for Tejashwi Yadav and RJD has declined among Muslims, Congress has managed to regain ground in Seemanchal—which includes Kishanganj, Araria, Purnia, and Katihar. Seemanchal was the region that Congress strategists selected for the Bihar leg of Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Yatra.

The party secured victories in Kishanganj and Katihar. Its resurgence in Seemanchal, combined with RJD’s decline, is something Congress is ready to capitalise on with a renewed strategy of courting Pasmanda Muslims, who comprise more than 80 per cent of Bihar’s Muslim population.

In the last week of January 2025, Ali Anwar Ansari, founder of Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz, was inducted into Congress’ fold—along with Bhagirath Manjhi, son of Mountain Man Dashrath Manjhi.

Ansari began his career as a journalist and later entered into political activism, focusing on demanding equality for Pasmanda Muslims. He claims he sees Hindus and Muslims in the same vein—being dominated by landowning upper-caste elites. One of his key demands has been the inclusion of Pasmanda Muslims under the larger frame of Scheduled Castes.

This demand was fulfilled in spirit by Nitish Kumar when he extended reservations and other welfare measures to OBCs and Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) sections among Muslims. Many credit Ansari’s influence over JD(U) for these policies. He represented JD(U) twice in the Rajya Sabha and is credited with pulling Muslim supporters of RJD towards Kumar.

However, over time, the contradiction of Ansari siding with a leader who was a coalition partner with BJP ultimately reached a level where Ansari had to leave JD(U) in 2017 when Kumar ditched the Mahagathbandhan—then composed of RJD, JD(U), and Congress. It was his meeting with Sonia Gandhi that triggered Ansari’s disqualification.

Ansari’s ability to galvanise votes will aid the popularity of Rahul Gandhi and his party. In Seemanchal, Gandhi is already more popular than Tejashwi Yadav, which explains why Yadav is making hyperaggressive statements to bring back his old Muslim support base.

What about the general castes among Hindus?

Congress’ push for Muslims and Dalits may take some time to materialise, but its chances of wooing 'upper castes' are going to be even more difficult.

Parties’ problems with 'upper castes' in Bihar are not as simple as giving representation to an elite few.

The key to upper caste voting puzzle lies in understanding the fragmentation of the upper castes as a voting bloc. The middle class of the upper castes—which forms a major influence in voting patterns—seeks protection for itself along with representation of its community, an expectation that cannot be fulfilled by mere token representation.

Congress is also trying to play by the old rules of giving representation to community leaders by offering a deputy chief minister from the upper caste, but for the time being, BJP seems to be ahead of the curve by choosing 18 out of 40 district heads from the upper caste in January 2025.

Additionally, Gandhi’s constant rattling on caste census will only worsen the upper castes’ residual confidence in the Congress.

The second problem is its alliance with RJD, which the 'upper castes' are still not sure about voting for.

In terms of difficulty level, currently, Muslims are the easiest to bring into Congress’ fold due to its direct opposition to BJP, while 'upper castes' are the most difficult. Careful planning for Dalit votes can actually pay more than expected dividends once Kumar is out of active politics.

In the 2020 AE, BJP, RJD, and JD(U)—three parties having larger clout than Congress in the state—gave 15, 19, and 18 tickets, respectively, to Scheduled Castes. Although Congress is not given much bandwidth by RJD, it could begin by demanding SC-dominated seats and then distributing tickets accordingly.

The question is, will Tejashwi agree?—especially given the current stature of parties in the Indian National Inclusive Developmental (INDI) Alliance.

Congress on 'rampage' after Delhi

When the formation was in its infancy, Congress needed regional parties to help it regain some lost ground. Although the party was (is) a national party with the highest seat count (52)—30 more than Trinamool Congress’ figure of 22 seats—it was reduced to just another regional player in meetings.

On the result day of 4 June 2024, Congress won 99 out of 326 seats it contested. In Bihar, it won two out of the nine seats—same as 2019—allocated to it by RJD. If we add Congressman Pappu Yadav—who contested as an independent due to opposition from RJD—Congress’ strike rate goes to 33.33 per cent.

On the other hand, Tejashwi Yadav could win only four seats for his RJD—with a meagre strike rate of 17.4 per cent. Yadav voters not turning up for Muslim candidates put another dent in RJD’s armoury while making space for Congress to expand its wings.

After the Lok Sabha election success, the party has become more assertive in its ideological positions. In Haryana, the party contested on 89 seats, leaving only one for the Communist Party of India (Marxist). It did not even give the desired seat to AAP, due to which the party contested separately.

Similarly, in Jharkhand, despite Hemant Soren’s popularity, Congress bargained hard to contest on 30 seats—just one less than 31 seats in 2019 when its bargaining power was much greater than in 2024.

It also gave a hard time to Akhilesh Yadav and Maharashtra allies for bypolls and AE, respectively, but could not punch above its weight.

However, in Delhi, Congress decided not to compromise and stood its ground, fielding candidates—primarily to diminish AAP’s chances—in all 70 constituencies. If linear vote transfer between alliance members is the norm, then the party can claim to have tasted success since on many seats it garnered more votes than the losing margin of AAP candidates.

Now the party high command seems to believe that even if it needs regional partners, its position at bargaining table is stronger due to its damaging abilities.

For Tejashwi Yadav, the writing is on the wall. Congress is basically coming up with two options for him.

Firstly, it will demand more seats and the freedom to choose its own candidates. If Yadav accepts it, he will have to leave a little more room in the alliance for Congress. This would mean choosing to tackle intra-alliance conflict in the future.

Secondly, if Yadav does not accord the desired respect to Congress, the party may go the Delhi route and emerge as a vote-cutter for the alliance. Yadav is already grappling with Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party trying to do the same.

The irony is that even though Congress wants to have independent vote banks in Bihar, it has to depend on RJD to do so.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.